Introduction to Hanafuda

Last updated: .

Hanafuda (花札, ‘flower cards’) are a type of playing card originating in Japan. They are also used in Korea, where they are known as hwatu (화투, ‘flower fight’, originally 花鬪), and in Hawaiʻi, where there is a large Japanese population. They are mostly used to play matching or set-collecting games, but they can also be used for complex gambling games.

Composition of the deck

Unlike Western playing cards which have 4 suits of 13 cards each, Hanafuda decks comprise 12 ‘suits’ of 4 cards each, giving 48 cards total. Each suit corresponds to a month, and is represented on the cards by a plant related to that month.

The months and their associated plants are:

January: pine (松 matsu)

February: plum (梅 ume)

March: cherry (桜 sakura)

April: wisteria (藤 fuji)

May: iris (菖蒲 ayame)

June: peony (牡丹 botan)

July: bush clover (萩 hagi)

August: silvergrass (芒/薄 susuki)

September: chrysanthemum (菊 kiku)

October: maple (紅葉 kōyō)

November: willow (柳 yanagi)

December: paulownia (桐 kiri)

In Korean and some Hawaiian decks, the months of November & December are switched. This rarely makes a difference except in some gambling games when the numeric order of the cards is used.

Types of card

The deck is divided into four categories of card. In descending order of value, these are: the “bright” (hikari) cards, the tane cards, the tanzaku cards, and the kasu cards.

Bright cards

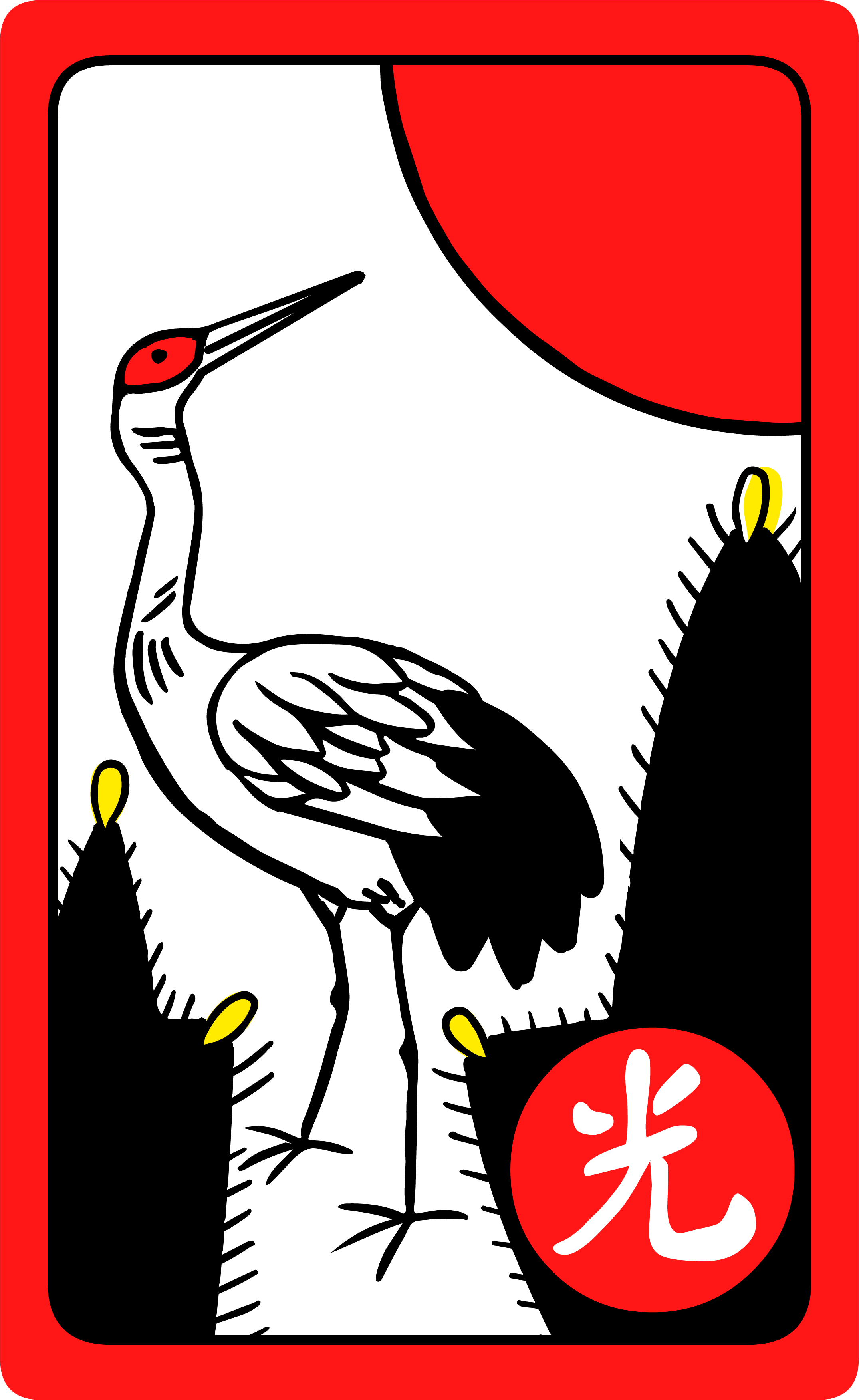

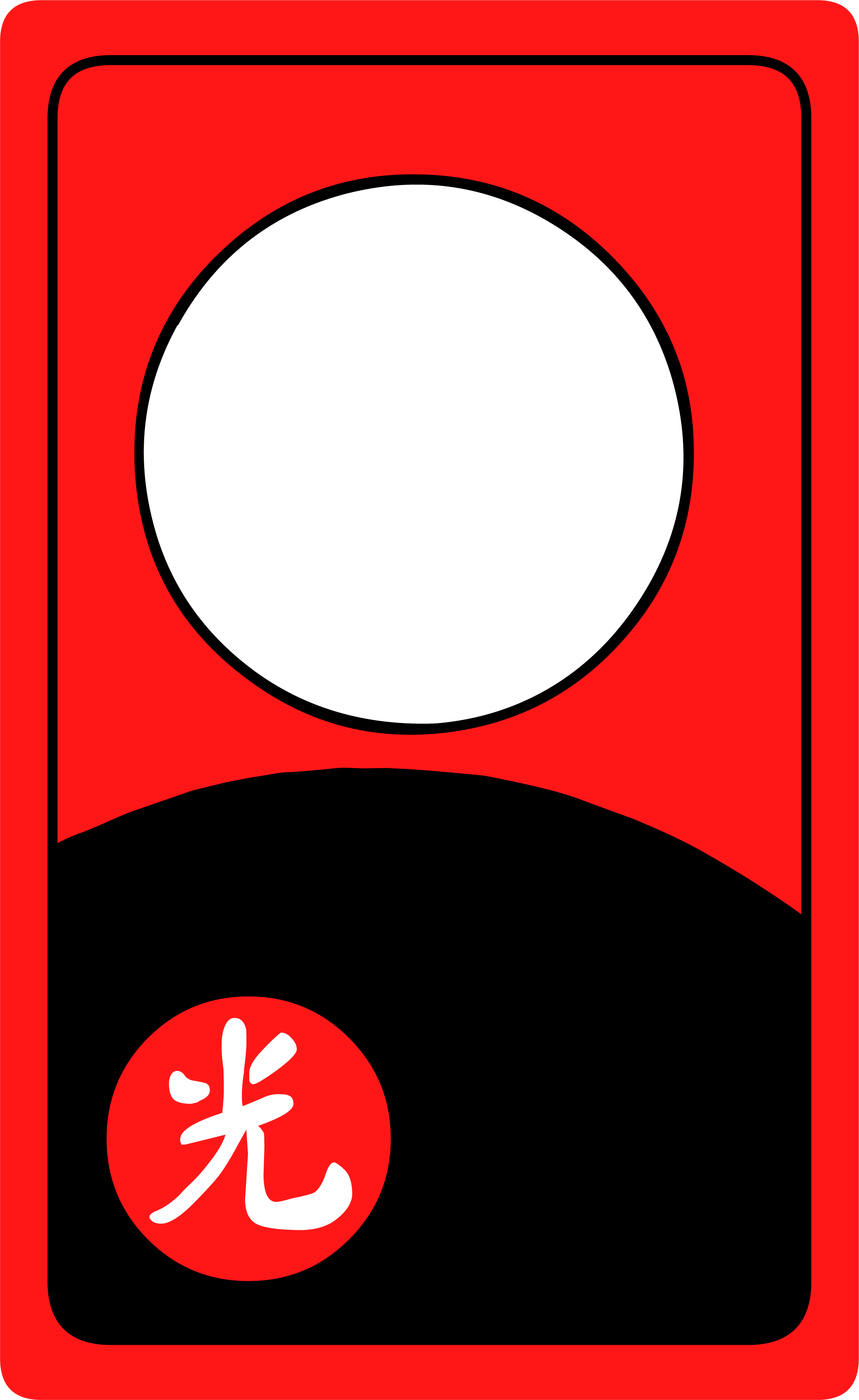

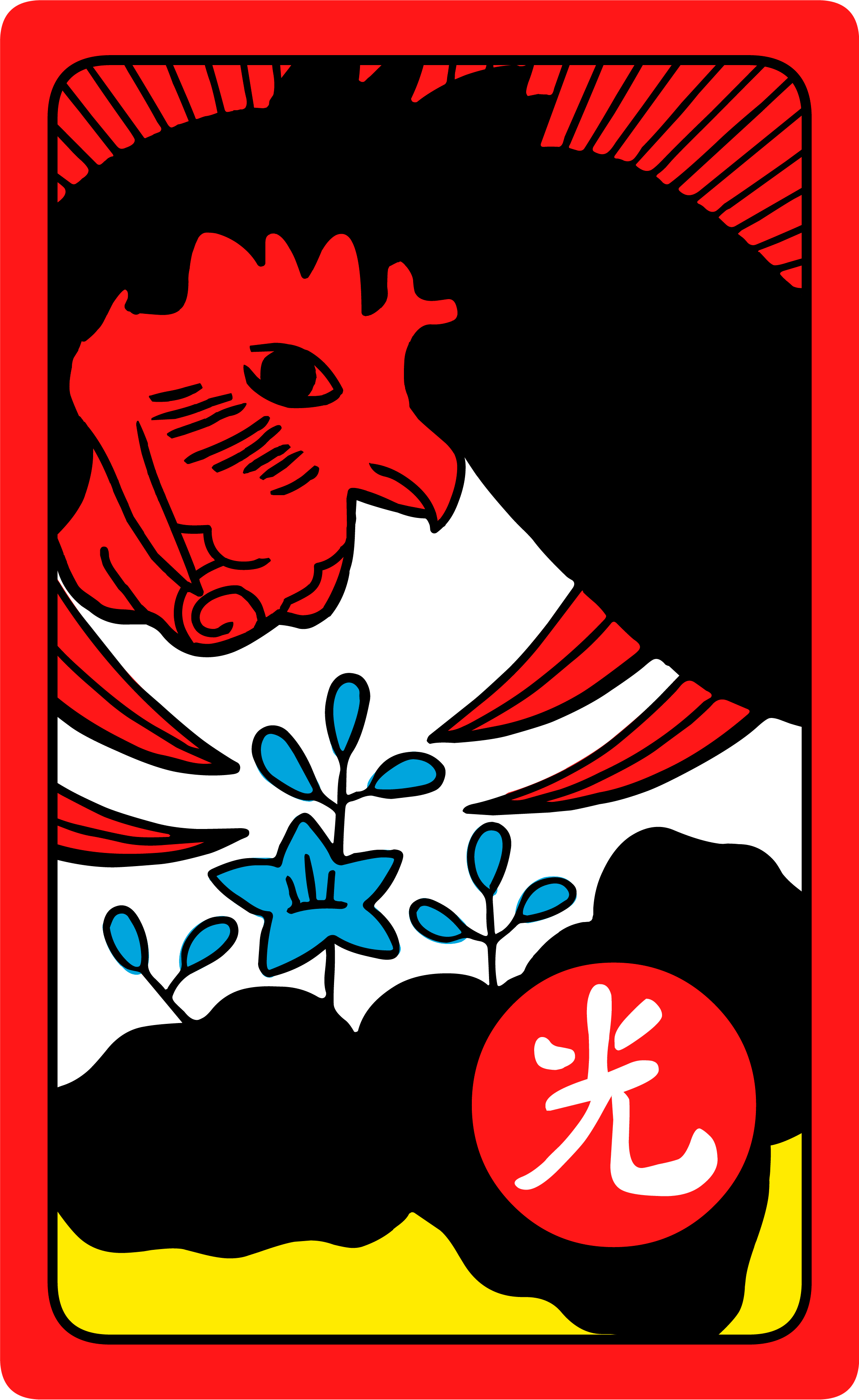

There are 5 ‘bright’ (光 hikari) cards. In most games, these are worth 20 points. The five bright cards are:

the crane with pine (January), 松に鶴 matsu ni tsuru

the cherry blossom curtain (March), 桜に幕 sakura ni maku

the full moon (August), 芒に月 susuki ni tsuki

the rain man (November), 柳に小野道風 yanagi ni Ono no Tōfū

the phoenix (December), 桐に鳳凰 kiri ni hōō

The five bright cards, from a standard Nintendo deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎The bright cards of a Japanese deck.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

In some decks, especially Korean ones, these are marked with the 光 character for ease of identification.Maeda Masafumi (前田雅文, d. 1998) of the manufacturer Ōishi Tengudō has claimed that these markings were actually a trademark-like feature that they used, which was picked up by the Korean manufacturers as a standardized marking.A

The five bright cards, from a Korean Pierrot (피에로) deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎The bright cards of a Korean deck.

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯🄎

Tane cards

There are 9 tane (種) cards, which are usually worth 10 points each. These cards mostly feature animals, but also a sake cup, and the ‘eight-planked bridge’.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎The 9 tane cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Tanzaku cards

There are 10 tanzaku (短冊) cards, usually worth 5 points each. These are the cards with the coloured ‘scrolls’ on them. Small pieces of paper were used to write poems on at poetry competitions (see the image below). For some games these are further subdivided into three sub-groups: tanzaku with writing, plain red tanzaku, and plain blue/purple tanzaku.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎The 10 tanzaku cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Maple with Poem Slips (c. 1675)

櫻楓短冊圖

A six-panel screen (one of a pair) by Tosa Mitsuoki (土佐 光起, 1617–1691).

Kasu cards

The remaining 24 cards that aren’t in one of the previous categories are called kasu (滓, ‘dregs’ or ‘junk’). They are usually worth a single point each. The first ten months have two kasu cards, but November has only one, and December has three.

These cards can be identified by their lack of distinguishing features. The odd one out is the “lightning card” of the November month, which is printed with a bold red & black pattern. One of the December kasu cards also has a yellow background and this card is treated specially in some games.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎 © 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎The 24 kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

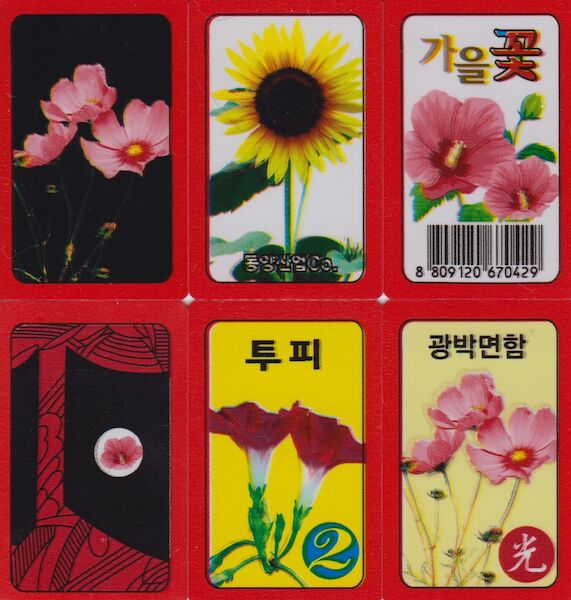

Extra cards

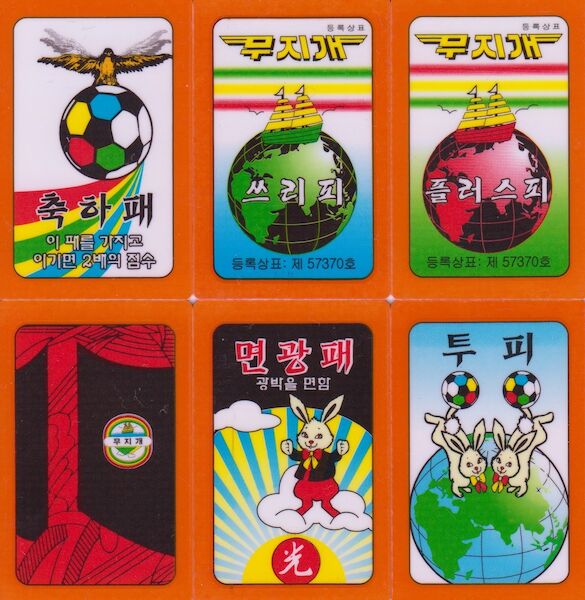

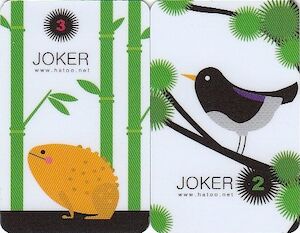

Korean decks often contain extra (up to six) joker cards. How these are used (if at all) depends upon the game being played. Many traditional Japanese decks also contain a white (白 shiro) blank card which can be used to replace a card if it is damaged or lost. Some Japanese decks also contain joker-like cards featuring oni (鬼, a Japanese ogre); see the next page for more examples of these.

Assorted jokers from a Korean Flower deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Assorted jokers from a Korean Rainbow deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Two joker cards from the Yongjaeng Hwatoo ‘Style’ deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Basic matching rules

Many Hanafuda games are of the ‘fishing’ variety, where each player tries to capture cards from a shared pool of cards in the centre of the table. The goal is to capture high-value cards or to form specific scoring patterns called yaku (役).

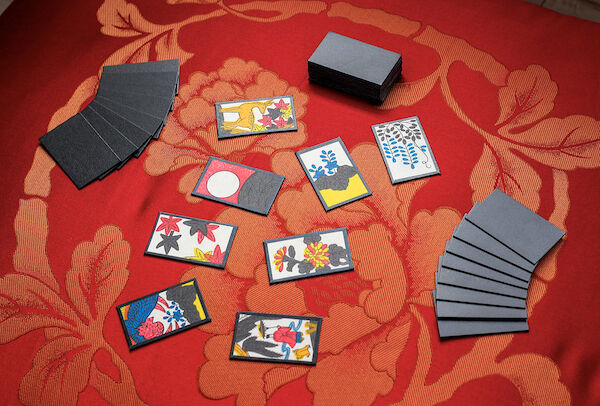

A sample setup for the game of Koi-Koi, with a pool of eight cards.

© 2021 Marcus Richert, 🅭🅯

In most Hanafuda fishing games a turn proceeds as follows:

First, the player chooses a card from their hand. If it matches (is of the same month as) one of the face-up cards in the pool, they place it face-up on top of that card. If it doesn’t match any of the cards in the pool, they lay it face-up in the pool next to the other cards.

Next, the player turns over the top card of the face-down deck. If it matches any of the single cards in the pool, they place the card on top of that one.

Finally, the player takes (‘captures’) any cards that were matched together out of the pool, and places them face-up in front of themselves. This ends their turn.

References

Fairbairn, John (). ‘Modern Korean Cards – A Japanese Perspective’. Journal of the International Playing-Card Society vol. 20 (1), : pages 68–72.