Chuck-a-Luck

Last updated: .

Chuck-A-Luck was a simple dicing game popular in the United States in the mid to late 19th century and early 20th century. It began as a portable soldier’s game and later developed into more complex casino variants.

Sweat-Cloth / Chuck-A-Luck

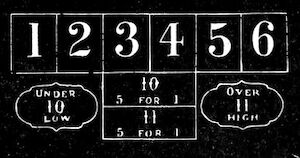

A professionally-produced Chuck-A-Luck layout, from Kernan Manufacturing’s Catalogue of Supplies for Saloon, Billiard Hall and Club Room Use (p. 19).

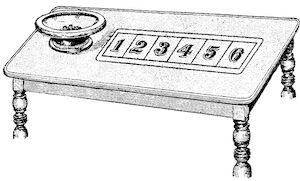

The play of the game is simple: there is a staking-board with six cells containing the numbers 1 through 6. Each player places their bet(s) on numbers of their choosing. The dealer or house rolls three dice and players whose numbers show up on the dice win. Bets on numbers that do not match any of the dice are won by the dealer.

Winning bets are paid at 1× the stake for each die that matches the number (so, a maximum of 3× if all three dice match).

These usual payouts lead to a relatively high house edge of 7.87%, and thus Chuck-A-Luck has an earned reputation of being a “suckers” game. In more modern casino variants the payout for all three dice matching is usually increased to make the game more attractive: a 5× payout still leads to a house edge of 6.94%, and even a 12× payoutAs used in the variant of Sic Bo that is played in New Zealand casinos. retains a house edge of 3.7%, higher than that of roulette.

History

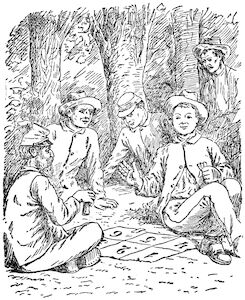

A depiction of soldiers playing Chuck-A-Luck, by George Y. Coffin.

From Corporal Si Klegg and his “Pard.”.

A game known as Sweat-ClothProbably in this context meaning a canvas saddle-cloth, upon which numbers were written to serve as a staking layout. was played since at least the early 19th century. The name could also be shortened to simply “Sweat”.C (p. 480) Gambling histories often cite an English origin, but I have yet to find any early mention of the game there.Although there are old English slang terms for gaming cloths, such as “tatty tog” from tatt ‘dice’ and tog ‘clothes’D (American derivatives of these sources note that this is equivalent to “sweat-cloth”E (p. 89)), I have yet to find reference to an actual game that is played with these cloths. The earliest reference I have found so far dates from 1808, when a man was indicted in Pennsylvania because he:F (p. 442)

… unlawfully did publicly and privately set up, erect, make, exercise, keep open, show and expose to be played at, drawn at and thrown at by dice, numbers and figures, a certain play and device called sweat-cloth

Another early reference to the equipment used in the game dates from 1810:

A Nicholas Creerly, has, in a Bucks county (Penn.) paper, in the uſual way, warned the public not to truſt his wife on his account, charging her with having deſtroyed his property, &c. His wife, in reply to this notice, ſays: “That he need not have taken this pains, as no perſon where he is known, will truſt her to the amount of a ſingle cent on his account, and as for bed and board, he never had any for her—and aſks how ſhe could deſtroy his property, when he never had any, except three dice, a sweat-cloth, and a rum bottle.”G

Other references from the 19th century show that in the United States the game was commonly played as a side-attraction at horse racing events:HI

What is a race-course but a convention of gambling hells out of doors, where, in a wider net, more of the weak and the vain are caught at the faro-bank or sweat-cloth, or induced in the excitement to bet on the horses?J

By 1830, the game began to be called Chuck-A-Luck (or simply Chuck-Luck), and this is the name that stuck. It was commonly played by soldiers and by the late 19th century was known as the “old soldier’s game”.This term is also used for Housie or Bingo.

A modern Chuck-a-Luck game on Coney Island.

© 2005 Avi Drissman, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

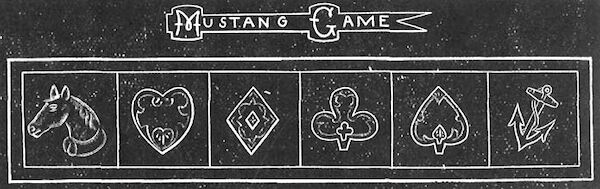

Pictorial dice

By the 1870s, the game also began to be manufactured with images instead of pips on the dice, and in this form it was called Mustang or Horse-Head (with dice with images of a horse’s head, anchor, and the card suit symbols: club, spade, diamond, and heart). In another form it was known as Feather and Anchor (horse-head, anchor, feather, game cock, leaf, star).K (p. 238)L (p. 532) Yet another form had the symbols: snake, elephant, eagle, baby, turtle (and 6th?).M (p. 283)

A Mustang layout, from Kernan Manufacturing’s Catalogue of Supplies for Saloon, Billiard Hall and Club Room Use (p. 19).

It is possible that it was one one of these pictorial versions that was taken and adopted by the British as Crown & Anchor.

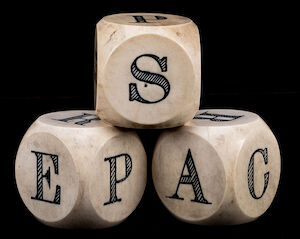

Three Hyronemus (see below) ball dice for use with Cubic Mutual Pool.

© 2018 Potter & Potter Auctions, used with permission

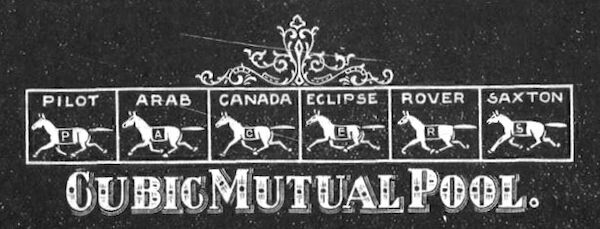

A Cubic Mutal Pool layout, from Kernan Manufacturing’s Catalogue of Supplies for Saloon, Billiard Hall and Club Room Use (p. 20).

The came was also transmuted into a horse-racing form, played using dice with sides marked . Under the name “Cubic Mutual Pool”, this was played as early as 1888.N

Casino Chuck-A-Luck / Grand Hazard

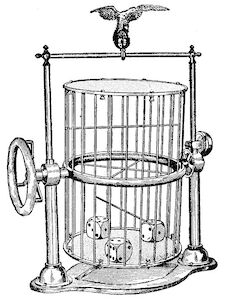

In casinos the basic game was augmented with equipment to become known as either “Hyronemus” (where the dice were spun in a bowl) or “Bird-Cage” (where the dice were tumbled inside a wire hourglass).

Chuk-A-Luck with an expanded staking board being played at the Bank Club, Reno, Nevada (c. 1932).

Many books of the time claim that these tools were often gaffed or crooked, with one advertisement for an Electric Hyronemus claiming it can be made to roll only “Treys and Fours” on command.

A hand-held “bird cage” for tossing Chuck-A-Luck dice (c. 1930).

© 2018 Potter & Potter Auctions, used with permission

A mounted “bird cage”, from Gambling and Gambling Devices (p. 118). The handle at the left is used to invert the cage, and this rings a bell mounted on the right. The top and bottom are made from taut leather and produce a drumming noise when the dice drop. (A video of one of these bird cages in action can be found on YouTube.)

Three ball dice for use in the Hyronemus tub; these dice have black and red faces so can also be used to run other side bets.

© 2018 Potter & Potter Auctions, used with permission

Hyronemus tub and staking layout, from Gambling and Gambling Devices (p. 119).

A Will & Finck–brand ‘Hyronemus tub’, which would be spun, driving the dice up to the rim, and then stopped so that they fell to the centre (c. 1890).

© 2018 Potter & Potter Auctions, used with permission

Extended Bets

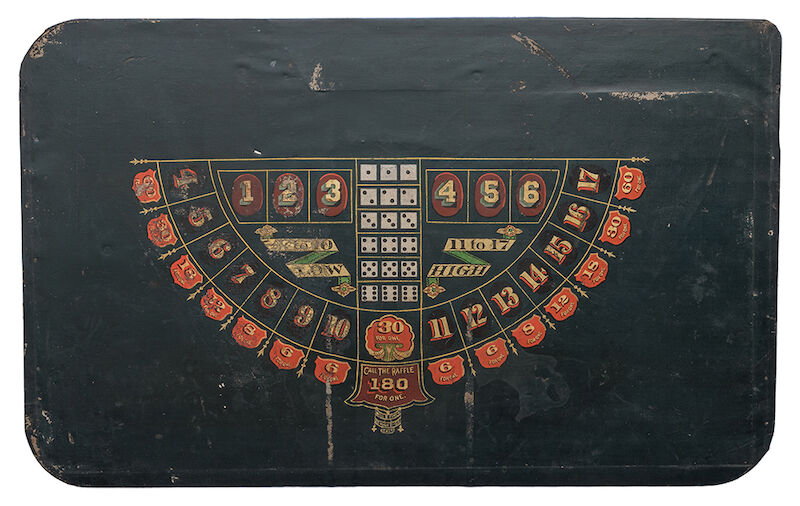

The basic 1–6 betting game was also extended to incorporate other types of bets. This version of the game could also be called Grand Hazard (despite its name, this has nothing to do with the earlier game of Hazard). These kinds of bets are still used in modern games run under the name of Chuck-A-Luck.

A Will & Finck Grand Hazard layout (c. 1890).

© 2018 Potter & Potter Auctions, used with permission

In addition to the “Chuck” bets, which are played in boxes labelled 1–6 as usual, the extended staking layout contains boxes for the following bets:

Raffles

A “raffle” is a three-of-a-kind. There are two different raffles bets that can be made: either that any raffle will come up, which pays 29∶1Note that the payments on the board in the image below are given as “30 for 1” and not “30 to 1”. This means that the stake counts as part of the winnings and thus increases the already-high house edge. (fair odds 35∶1), or else a bet can be placed on a specific raffle, which pays 179∶1 (fair odds 216∶1). Both bets have the same high house edge of 16.67% and so in the long-term are equivalent bets.

More modern versions of the game might pay out 30∶1 for any 3-of-a-kind, which has a slightly lower edge of 13.89%.

Low (≤10) or High (≥11)

These bets are on what the total number of pips showing on the dice will be. Both would be even bets except that they lose on a raffle. They have the same odds and pay 1∶1 (fair 37∶35); the house edge is the lowest on the board at 2.78%.

Specific totals

Each total is paid out at a different rate. All have extremely high house edges:

Values

Paid

Fair

Edge

10, 11

5∶1

7∶1

25.00%

9, 12

5∶1

7.64∶1

(191∶25)30.56%

8, 13

7∶1

≈9.3∶1

(65∶7)22.22%

7, 14

11∶1

13.4∶1

(67∶5)16.67%

6, 15

17∶1

20.6∶1

(103∶5)16.67%

5, 16

29∶1

35∶1

16.67%

4, 17

59∶1

71∶1

16.67%

Other Hyronemus Bets

A Hyronemus layout, from Gambling and Gambling Devices (p. 117).

Some bets seen on Hyronemus layouts are based on the sum of the dice:

Low (<10) and High (>11)

Both of these are bad bets, paying 1∶1 (fair odds 1⅔∶1) for a house edge of 25%.

10 · 11

Both of these are worse bets, paying 4∶1 (fair odds 7∶1) for a house edge of 37.5%!

Field Bets

Other versions of the game include “field” bets, which are a bet that the dice pip total will be one of a range of numbers. These bets always pay 1∶1.

Examples include:

5 · 6 · 7 · 8 / 13 · 14 · 15 · 16

This field has a house edge of 3.7%.

3 · 4 · 5 · 6 · 7 / 13 · 14 · 15 · 16 · 17 · 18

Despite having more numbers, this field excludes the common ‘8’, and has a house edge of 15.74%.

There are also two-dice fields, where two of the three dice are coloured differently to the third, and the field value is based upon their total:

2 · 3 · 4 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12

As seen on layouts produced by Taylor & Co. or the K. C. Card Company. The house edge on this field is 11.11%.

2 · 3 · 5 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12

As seen on layouts produced by Mason & Co. The house edge on this field is 5.56%.

Fairground variants

Given the high house edge on all Chuck-A-Luck bets, it wouldn’t seem that any further advantage would be needed—but gambling operators apparently didn’t think so. Further developments of the game increased the returns for the operators.

3-Spindle Chuck-A-Luck

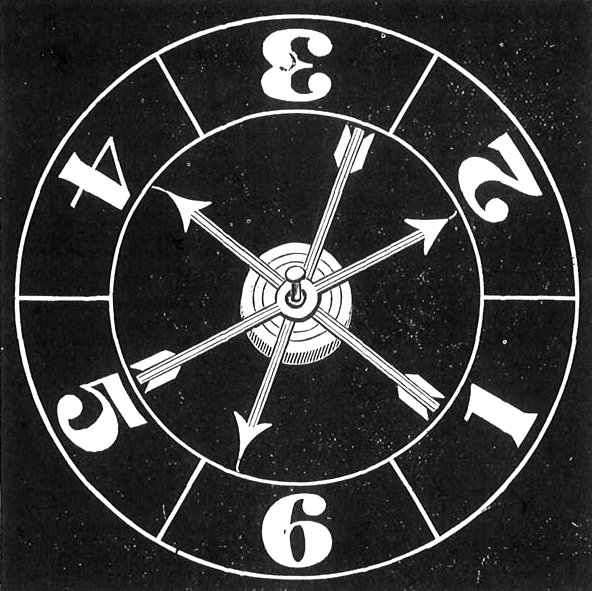

This version has three separately-rotating spindles, and has exactly the same odds and house edge as standard Chuck-A-Luck.

As found in Kernan Manufacturing’s Catalogue of Supplies for Saloon, Billiard Hall and Club Room Use (p. 26).

Spindle Chuck-A-Luck

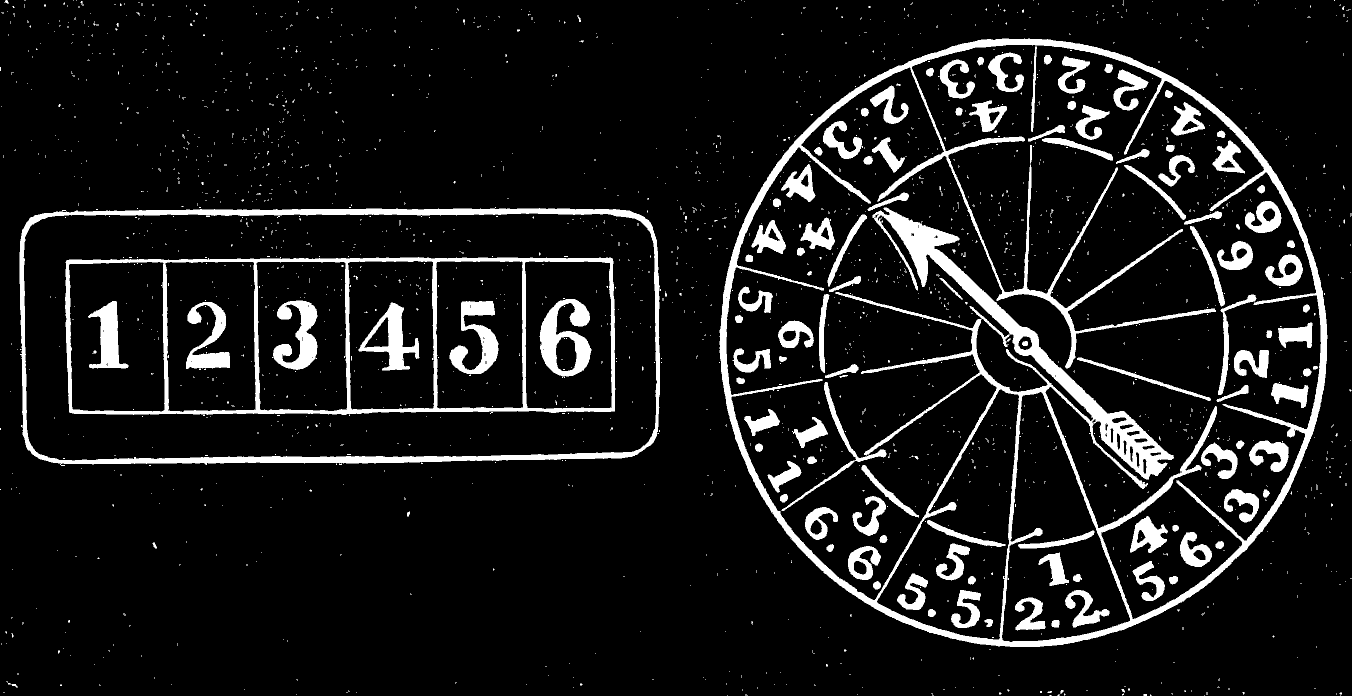

This version of the game used a single spindle, which is spun, and the numbers that it lands on are the winners. Since the distribution of the numbers is different to the distribution given by dice, the house edge is higher than normal. The manufacturer claimed that it would double the usual take, but in reality the edge is nearly three times higher, at 21.43%.

If this wasn’t enough, the game was often played with a gaffed wheel that allowed the operator to stop the spindle spinning at will.

An H. C. Evans & Co. spindle and layout from their 1909–10 catalogue, as reproduced in Gambling and Gambling Devices (p. 145).

Jumbo Dice Wheel (Big Six)

The standard version of this nowadays (at least in the United States) is a wheel-of-fortune with money printed on it, but in its earliest form the wheel had dice drawn in each sector. As with Spindle Chuck-A-Luck, the distribution of the dice rolls has been manipulated to provide the operator extra income. The house edge on the wheel on the right below, with 48 sectors, is 14.583%. The edge on the wheel at left, with 54 sectors, is 12.963%.Or at least, it is intended to be. The wheel represented here seems to have an error where one 5 has been switched with a 3, so the edge on those two numbers is different. (ScarneP (pp. 501–3) miscalculates the house edge on this wheel as 22.22%, as it seems has was working from a different version than shown in the photo in his book.)

In general the more doubles or triples on the wheel, the worse the odds are for the players.

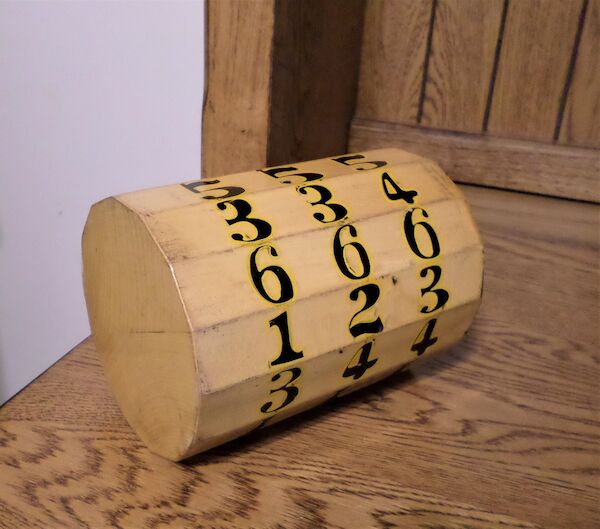

Chuck-a-Luck log

This form of the game was apparently invented to circumvent restrictions on gambling with dice or wheels. The log pictured below has 14 sides and was probably manufactured by H. C. Evans some time around the 1930s–50s. Pete Angelos who supplied the image calculates the house edge at 21.4% (the same as the spindle version above).

A rolling log version of Chuck-a-Luck.

© 2012 Pete Angelos, used with permission

References

Kernan Manufacturing Co. (). Catalogue of Supplies for Saloon, Billiard Hall and Club Room Use. Kernan Manufacturing Co.: Chicago, IL, USA.

Hinman, Wilbur F. (). Corporal Si Klegg and his “Pard.”. The Williams Publishing Company: Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Dick, William Brisbane (). The American Hoyle (4th edition). Dick & Fitzgerald: New York, NY, USA.

Andrewes, George (). A Dictionary of the Slang and Cant Languages: Ancient and Modern. George Smeeton: Covent Garden.

Matsell, George W. (). Vocabulum; or, the Rogue’s Lexicon. George W. Matsell & Co.: New York, NY, USA.

Wharton, Francis (). Precedents of indictments and pleas, adapted to the use both of the courts of the United States and those of all the several states: together with notes on criminal pleading and practice, embracing the English and American authorities generally. James Kay, Jr. & Brother: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘American Intelligence’. Maryland Gazette, .

Anonymous (). ‘The Chief of His Tribe: The Life and Times of John Thomas Tumbler, Jr.’. The Knickerbocker, : pages 252–258.

“M” (). ‘The Camden Race Course’. The Friend vol. 18 (39), : pages 305–6. Joseph Kite & Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Nadal, B. H. (). ‘Games of Chance as an Amusement’. The Ladies’ Repository, : pages 252–258.

O’Connor, John (). Wanderings of a Vagabond. John O’Connor: New York.

Dacus, Joseph A. and James W. Buel (). A Tour of St. Louis. Western Publishing Company: St. Louis, MO, USA.

Quinn, John Philip (). Fools of Fortune, or, Gambling and Gamblers. G. L. Howe & Co.: Chicago, IL, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Armourdale’. The Weekly Gazette, : page 8. Kansas City, Kansas, USA.

Quinn, John Philip (). Gambling and Gambling Devices. J. P. Quinn Co.: Canton, OH, USA.

Scarne, John (). Scarne’s New Complete Guide to Gambling. Fireside Books.