Crown & Anchor

Last updated: .

Crown & Anchor is a dice game using three special dice that is probably most famous as being popular with British and “Colonial” servicemen in the early 20th century, but today it is played in many locations around the world.

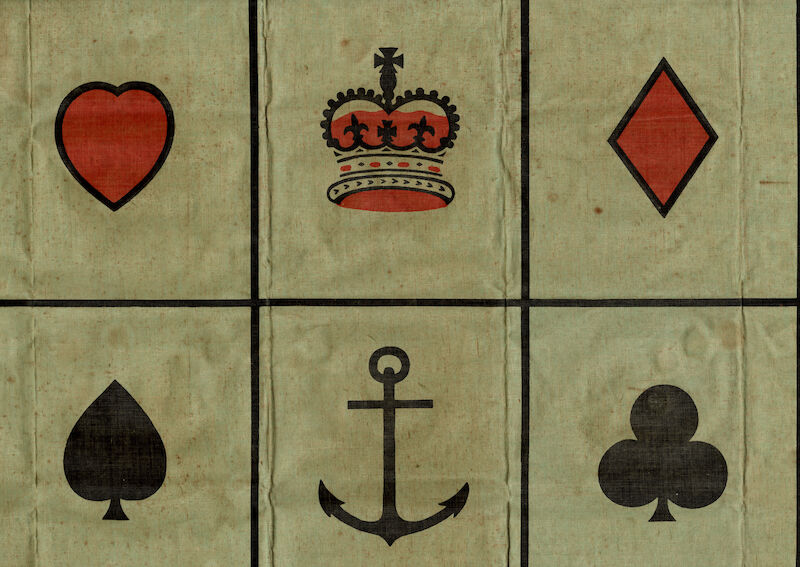

The game play is equivalent to that of Chuck-a-Luck, but the pips on the dice and the numbers on the staking-table are replaced by symbols: the titular 👑︎ crown and ⚓︎ anchor, and the playing-card suits: spade, club, diamond, and heart.

Crown & Anchor dice from the early 20th century.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

History

‘It’s a fair game,’ he was saying; ‘it’s a fair game. The wee boy has the same chance as the old man, and the old man as the wee boy.’A (p. 210)

Please note that the following is (necessarily, for me) biased toward English-language sources. It is entirely possible the game has a longer history elsewhere; for the moment, at least, I cannot say.

A Crown & Anchor mat purchased in Colombo (Sri Lanka) in 1915 and used by Australian troops while in transport.

Many gaming histories cite a 17th or 18th century origin for the game, but based on textual evidence it seems to date from the late 19th century (at least in the version played with the Crown and Anchor symbols), possibly derived from pictorial versions of Chuck-A-Luck such as “Mustang”. In England there are certainly many old references to “dice boards” or “gaming tables”, but they are not described in detail very often.

At first, the game was played with symbols other than the crown and anchor. The earliest reference I have found is to a version played with “anchors, stars, clubs, spades, hearts, and diamonds” at the coronation fair of George IV in Hyde Park in 1821.This is clearly the same game as six outcomes are listed and the operator announces “three to win, three to lose” — a classically misleading claim!B

Other variants were developed through the 19th century: In 1842, the Punch character Mr. Muff “mistrust[s] the chances of the ‘Dimunt, Star, Hanker, Crown, Club, and Feather’” being played at the (fictional) “Clodpole races”.C In 1859 a game involving “anchor, heart, etc” is described at a fair,D and in 1860 “clubs, spades, &c.” at a game at the races.E An 1864 newspaper article claims that Deacon Brodie played a game of “anchor, club, star, feather, heart, [and] spade” in his youth, but this may be anachronistic — in any case, it is still an early reference.F In 1875 there is reference to a game of “feather, star, and anchor” being played in Epping Forest.G In 1889, chuck-a-luck (as the “three dice game”) is reported in Middlesbrough.H

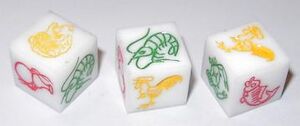

Modern versions of “anchor & sun” dice.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

Early references to the game under the name anker en zon (“anchor and sun”) appear in Flanders in 1880,I and finally as “the crown and anchor game” in Melbourne,The game under the name of Chuck-a-Luck or “old sweat” is known in Melbourne from at least 1866.J Australia in 1882.K An equivalent game is recorded as being played in British-controlled Hong Kong in 1884.L

Information from the people who actually ran the games is hard to find. One notable exception is that of Arthur Harding, whose memoir details his life growing up in The Nichol,The Nichol was a slum in East London, also called the “Jago”, which was torn down in the 1890s. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.M Harding states that “some of the first pennies [he] earned was holding up the boards for ‘Crown and Anchor’”, and describes how the board would be held by a person at each end, with a cloth on which the staking layout was painted placed on top. The entire setup was designed to make it as easy as possible to disappear when the police arrived, although in many cases the games were tolerated by police as the income the games provided prevented the operators from resorting to harder crimes.Such as “snide-pitching” (passing false money), and “shoot-flying” (stealing pocket watches by grabbing their chains)!M (pp. 175–8)

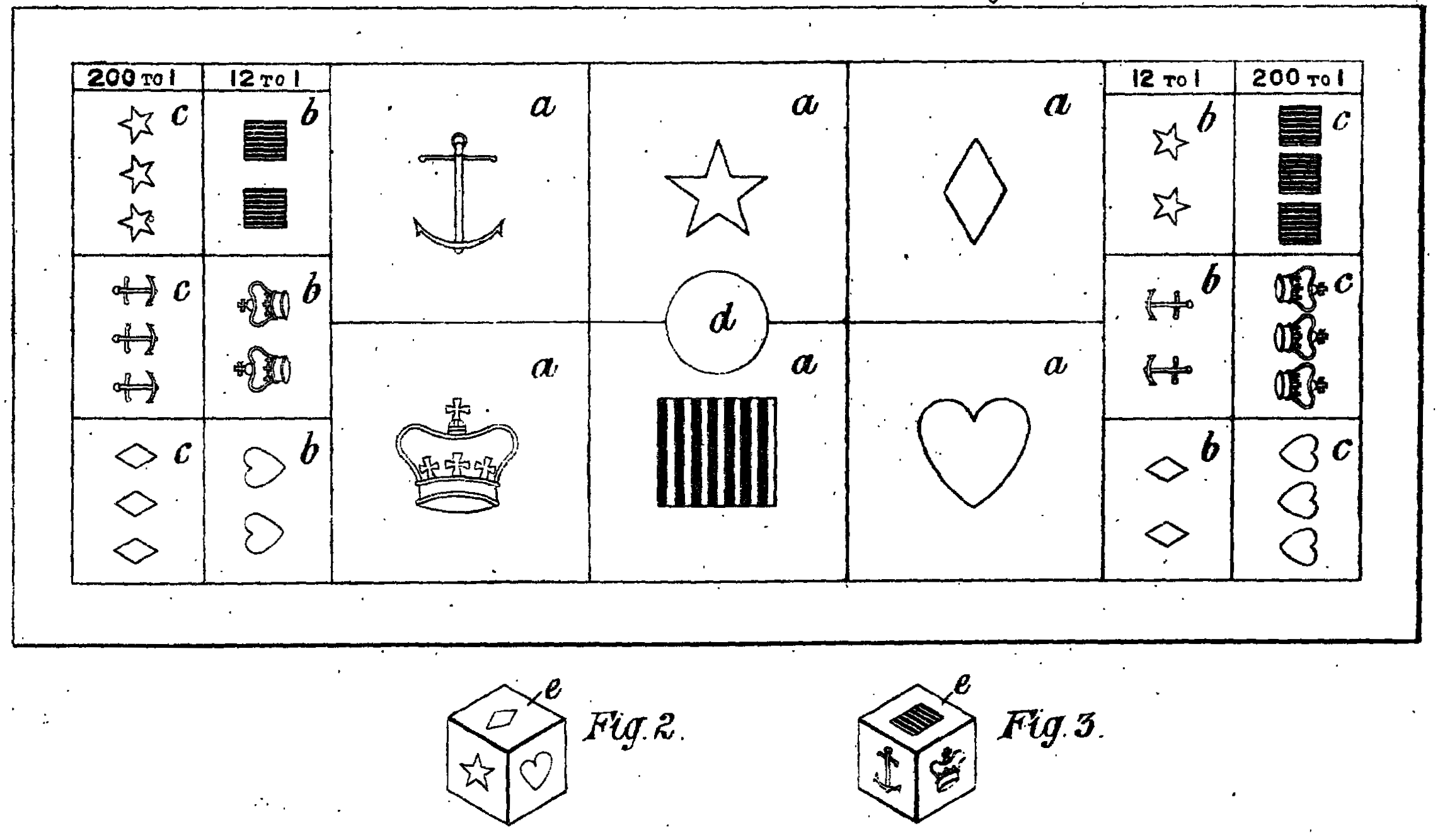

An interesting patent lodged in England in 1895 (see image) indicates that the crown-and-anchor version of the game must have been known at that time, but I have yet to find any other references to it this early on, and the patent does not mention Crown & Anchor by name.P

An image from the patent for the game “Stars and Stripes”.

The game has also at times been called “bubble and buck”,Q “bumble and buck”,R (p. 189) “diddlum buck”S (p. 44) or “toodlum buck(s)”.This name was also used in Australia to refer to a children’s game played with a teetotum; perhaps the version on sale here is Crown & Anchor played with a teetotum.T

Boer War

The game seems to have first became popular with British soldiers during the Second Boer War (1899–1902), when British and Australian troops fought alongside American volunteers. It was possibly transmitted from American troops at this time. Sir Bertram Fox Hayes describes the game being played aboard his ship,The SS Britannic. while transporting troops to South Africa.U (p. 103) In 1900, the game is recorded as having been played by English POWs at the Waterval prison camp, under both the names of “chuck-a-luck”V and “crown and anchor”.W British soldiers’ diaries also record the game being played in military camps at De AarX (p. 391) and on transport ships.Y (p. 157)

In 1902, the game was described in London as “a new game from South Africa”,Z and a syndicated article from 1914 also discusses the game as having been played in the army “since the first South African campaign”.AA

References from the end of the Boer War period refer to returning British soldiers being swindled at the game,AB returning Australian troops playing it aboard transport ships (including the last troopship the Drayton Grange,AC which returned over-crowded and disease-ridden), and a report by an American who played the game with English troops.AD

World War I

British gun crews with two 9″ guns, May 1918; the counterweight “dirt box” in front is painted with Crown & Anchor iconography.

At the beginning of WWI the game was, at least at first, still unfamiliar to many British soldiers, and seems to have been most strongly associated with Australian troops. Sam Sutcliffe described a camp scene at Abbassia in 1915:AE (p. 191)

Gambling was forbidden to us and, officially, it may have been to them, but a mighty sight worth seeing was the Australian Crown And Anchor school. Soon after dusk, quite some distance from their camp, a line of little lights would commence to twinkle. Curiosity lured me over there, spiced by the knowledge that, if our Military Police caught me near those wicked Aussies, I’d be in real trouble.English troops were not permitted to mingle with the Australians. I believe I planned to vanish into the dark desert if trouble threatened, and make my merry way back to our camp later.

I found a long line of improvised desks, a space of several yards between each of them. A couple of candles on each desk illuminated the Crown And Anchor board — actually a leatherette sheet, easily folded up and pocketed in an emergency, with the six symbols of the game printed on it. The operator sat on a box and called out his line of persuasion or temptation, such as “Come on, me lucky lads! The more you put down the more you pick up. Who’ll have a bet on the old mudhook?”i.e. anchor, see below.

Some operators always had a group of punters around them, others did less business. Why should some be more successful than others, even there at the edge of the desert? All had the same set-up, although they did vary the odds. The lowest offer made was to double your money if the symbol you’d backed turned up when the dice was thrown. Perhaps the variations which could be introduced by ingenious operators attracted men who applied careful thought to their gambling. Watching from my respectful distance, I was very impressed, at times amazed, at the quantity of money which changed hands.

Australians playing Crown & Anchor aboard HMAT Medic, c. 1919.

As seen in the last quote, each symbol had its own nickname. The crown could also be termed the “sergeant-major” or “Teddy’s hat”, the spade the “shovel” or “pioneer’s tool”, the diamond the “curse” or “Kimberley”, the heart the “jam tart”, the club the “shamrock”, and the anchor the “mud-hook”, “mud-rake”, or “meat-hook”.R (pp. 187-8)AF

According to several observers, the game was even played on the frontlines, in trenches. An anecdote from the Ypres Salient in 1916, by a soldier of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps:AG

Alf, who owned a Crown and Anchor board of great antiquity, had it spread out on two petrol cans at the bottom of a shell-hole.

Around it four of us squatted and began to deposit thereon our dirty half- and one-franc notes, with occasional coins of lesser value. The constant whistle of passing fragments was punctuated by the voice of Alf calling upon the company to “’ave a bit on the ’eart” or alternately to “’ave a dig in the grave”, when a spent bullet crashed on his tin hat and fell with a thud into the crown square.

“’struth,” gasped Alf, “old squarehead wants to back the sergeant-major.” He gave a final shake to the cup and exposed the dice — one heart and two crowns. “Blimey,” exclaimed Alf, “would yer blinkin’ well believe it? Jerry’s backed a winner. ’Arf a mo,” and picking up the spent bullet, he threw it with all his might towards the German lines, exclaiming, “’Ere’s yer blinking bet back, Jerry, and ’ere’s yer winnings.” He cautiously fired two rounds.

Similar samples of the proprietors’ patter resound from many memoirs of the war:R (p. 178)

Where you lay we pay. Come and put your money with the lucky old man. I touch the money, but I never touch the dice. Any more for the lucky old heart? Make it even on the lucky old heart. Are you all done, gentlemen? … Are you all done? … The diamond, meat-hook, and lucky old sergeant-major. (He shakes the dice again.) Now, then, will any one down on his luck put a little bit of snow (some silver) on the curse? Does any one say a bit of snow on the old hook? Are you all done, gentlemen? Are you all done? … Cocked dice are no man’s dice. Change your bets or double them! Now, then, up she comes again. The mud-rake, the shamrock, and the lucky old heart. Copper to copper, silver to silver, and gold to gold We shall have to drag the old anchor a bit. (Rattles the dice.) Now who tries his luck on the name of the game?

Another report from Gallipoli in 1916 also mentions it being played in trenches, and indicates that it was associated with “colonials” (Australians and New Zealanders):AH

I am satisifed there is as much chance of stopping colonials gambling as old Canute had of stopping the tide rising. I have see them playing “crown and anchor,” a great game with them (don’t know if you ever saw it) in all sorts of unlikely places, even on the fire step in first line trenches. It was funny on the Ionian, going back to Egypt, when there was a church parade. The padre paused in the sermon, and in the middle of the silence came a yell from behind the deck-house, “Who’s going to put a bob on the lucky old mud hook?” whilst straight on the bridge, and absolutely the nearest to the parson, was a ring of men gambling all the time, and too straight under the parson for him to see them. It did look comical…

In 1917 it was described as being played by “colonial” New Zealanders at an English NCO school:AI

Colonial slang appears strange to the “Tommy,” […] an invitation to a game of “pounds, coins, or browns” lets one know that the popoular gambling game of “crown and anchor,” for anything from a £1 note to a penny, is in progress.

In 1916, one author reported that a local toy store in Boulogne was selling game sets to English troops.AJ (p. 66)

Despite all the previous quotations, some American troops believed it to be a British game.AK (p. 369)AL (p. 66)

Canadian troops also report playing the game during the war.AM (p. 94)AN (pp. 21, 140)

In 1919, it was reported to be played on the ill-fated returning Australian transport Sardinia.AO

Post-war memoirs indicate that the game was commonly played in POW camps as in the Boer War, including the German camp Münster II (AKA K47, Rennbahn), although gambling games were not permitted to be played.AP (pp. 204–6)

World War II

In 1940, it was reported that Australian Imperial Force troops stationed in Mandatory Palestine had figured out how to play the game without dice: several slaters were placed under an upturned ashtray which had indentations for resting cigarettes; the holes from which the slaters emerged determined the winning numbers.AQ

A “St. George Series” Crown & Anchor board, c. 1930s?

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Post-War

After the first and second World Wars, mentions of the game become much more common, as the game diffused from returning soldiery back into the wider population.

A version of the game played by workers constructing Scotland’s hydro-electric dams in the middle of the 20th century was played with six dice, but two matches were required to win anything.AR (pp. 162–163) This version of the game has a much higher house edge of 13.865%.

Around the World

Countries known to play Crown & Anchor.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The game is played in many locations around the world, some of which are described below. Note that American-style games including casino versions are discussed in the Chuck-a-Luck article.

China and amongst Peranakans

Modern Chinese dice.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

In English the Chinese name is usually given as “Hoo Hey How”; this appears to derive from the Hokkien hû hê hāu 魚蝦鱟.AS (p. 109) The modern Chinese name is 魚蝦蟹/鱼虾鲎 ‘fish prawn crab’; these are several of the symbols that commonly appear on the staking layout.

Example of a Chinese-style staking layout. At the top is the manufacturer’s name 高慶坊 Gāo Qìng Fāng, followed by 翹骰不算 “cocked dice don’t count”.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

An equivalent (perhaps older) game can be played with three standard six-sided dice. It does not need to be played with a layout board but it can be. In this form it can be called 么二三 io jī sam (‘ace, two, three’, romanized “Yew Yee Sam” in older texts).AS (p. 95)

‘Grasping Eight’

CulinAT (p. 495–6) describes a very similar game that he calls “Grasping Eight” (八㪥, Cantonese: baat³ zaa¹),Culin transcribes this as pát chá. which uses eight dice.

The staking board contains the six squares with the dice symbols

, and players place their stakes on the squares. The eight dice are rolled. If at least three match a number, the players who staked on that number win 8×; if at least six match, they win 16×. All other stakes are lost.

Indochina

The game is widely played across the countries of the Indochinese peninsula, despite gambling being illegal in most of them. The presentation of the game is very similar in all regions.

Vietnam

The Vietnamese game has a similar æsthetic to the Chinese version, including the name: bầu cua tôm cá (‘gourd crab prawn fish’).

Modern Vietnamese dice, made out of paper.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

Three dice as used in the Vietnamese game.

© Shutterstock.com/Marie Shark: 541065082

Thailand

I have little information about the game in Thailand other than that the paraphernalia for playing exists; gambling is illegal in Thailand.

Modern Thai dice.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

From what little I have seen, the game is called (น้ำ)เต้า ปู ปลา ((nam)tao pu pla, ‘(water)gourd crab fish’).AU (p. 85) The images that the game is played with are: goldfish (ปลาทอง pla-thong), chicken (ไก่ kai), crab (ปู pu), gourd (เต้า tao), tiger (เสือ suea), and shrimp (กุ้ง kung). Sometimes a frog (กบ kop) appears instead of a tiger.AU (p. 85)

It is possible, although difficult, to obtain official permission to play the game at funerals.AU (p. 86)

Dice with Thai names.

© Shutterstock.com/jointstar : 319181276

Cambodia

In Khmer the game is called ខ្លាឃ្លោក khlaa khlook (‘tiger and gourds’),AV and the images are usually tiger, gourd, chicken, prawn, crab, fish. As in Thailand, gambling is illegal.

Myanmar

The name of the game appears to be ဂျောက်ဂျက် gjau’ gje’,AW but I have no other information.

Laos

Again I have little information about the game here. Some images of the game being played in Laos follow. Interestingly, both photos show a board with Thai names.

India and Nepal

The game was known in Mumbai and PuneThen called Bombay and Poona. as early as 1905, as indicated by court cases from the time,AXAY but it may have been in India for a long time prior to that.

In current times, the game is called झंडी मुंडा Jhaṇḍī Muṇḍā (“flag crown”?), or खोर खोरे Khor Khore.

Gambling remains illegal in most of India but the game is commonly played during Diwali.

An example of a staking layout for Jhaṇḍī Muṇḍā.

Note that the heart is presented with the same orientation as the spade; this appears to be a typical feature (see more examples: 1, 2).

© Shutterstock.com/rajanpy : 1958829937

The names of the symbols are (in Hindi):

flag: झंडी jhaṇḍī (flag, specifically a triangular flag associated with Hinduism)

crown: मुंडा muṇḍā (“shaven”?)/बुर्जा burjā (tower?)/मुकुट mukuṭ (crown)

spade: हुकुम hukum

club: चिड़ी ciṛī

diamond: ईंट īṇṭ (literally ‘brick’)

heart: पान pān (‘betel leaf’)

The game being played with 6 dice in Pokhara, Nepal.

© 2017 Shutterstock.com/Kondoruk : 1035142783

Modern dice for the Nepalese game.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

In Nepal the game is called langur burja (लंगूर or लङ्गुर बुर्जा).Langur would seem to derive from the Hindi लंगर langar, “anchor”, but the association has been lost in Nepal as the anchor symbol was replaced by a flag. It is commonly played during the festivals of Dashain (दशैं) and Tihar (तिहार), and it is usually played with six dice (requiring a minimum of two matches to pay out).

Some Nepali names for the playing-card symbols are:

spade: सुरथ surath

club: चीड chid (‘pine’)

diamond इँट itta (‘brick’)

heart: पान pana (‘betel leaf’)

Malaysia and Brunei

Modern Malaysian dice.

© Arjan Verweij, used with permission

In Malaysia the game can be known as ikan, udang, dan ketam (‘fish, shrimp, and crab’), ketam-ketam (‘crabs’), or yu ha hai (derived from a non-Mandarin pronunciation of the Chinese name). Chinese-style staking layouts are often used.

The game is very popular amongst the Kadazan–Dusun people of Sabah (Northern Borneo), where it is known as katam-katam (‘crabs’). It is played during the festive season and also at funerals.

In Brunei the game is also known as katam-katam.AZ

Bali and Indonesia

In Bali the game is played in many forms and known under many names: mong-mongan (the name of a set of three small gongs used in Sumatra), or one of a variety of similar names such as kocok(an) (‘shake’/‘shaking’, as of the dice), koprok, kolok, or kopyok(an) (also ‘shake’/‘shaker’; used also for lotteries).BA

Bali is (based on appearances on the internet) possibly the part of the world where the game is currently the most popular; this despite all gambling being illegal in the country.

As in many cultures, gambling is often associated with religious festivals. While other Balinese gambling activities such as the cock-fight are restricted to men, the game can be played by anyone, including young children.

A game being played with 6 dice and 12 squares (including one featuring the Teletubbies!) at Pura Samuan Tiga temple; note the men wearing traditional Balinese dress including udeng.

© 2011 Walther Tjon Pian Gi , 🅭🅯🄏⊜

In the Balinese game, bets can be placed spanning two symbols.

Some of the sets of symbols used are:

basir, robin, rare (baby), ikan barong (fish Barong), kepiting (crab), ayam (chicken); see images below

basir, bayi ajaib (magic baby), [???], [a duck], macan (tiger), elang (Javan hawk-eagle)Seen here.

kak tua (grandfather), elang, cewek (girl), singa (lion), ikan (fish), kodok (frog)Seen here.

A game being played in Bali: bets are placed…

© 2013 Shutterstock.com/Novie Charleen Magne : 1350321158

…and the dice are revealed.

© 2013 Shutterstock.com/Novie Charleen Magne : 1350321164

The game can also be played without symbols, but the dice used are still very highly stylized:

A Balinese game played without imagery.

© 2017 Shutterstock.com/Nomad1988 : 1398460952

West Indies

The game was probably played throughout the British West Indies; there are records of it from Trinidad,BB (p. 692) Antigua, Jamaica, and Bermuda.BC (pp. 622–3)

The game is still played today in Jamaica.

A busy game being played during the Cup Match in Bermuda.

In Bermuda, the game is legal during the weekend of the Cup Match (a cricket tournament), and played in large tents known as the “stock market”.BD (p. 267) It is also known as Hook and Hat.BE (p. 123)

Fairground variants

As with Chuck-a-Luck, the game has been adapted for mass play at fairgrounds and carnivals. As noted on that article, the modified games usually have worse odds for the players.

A Crown & Anchor wheel in Toronto.

See also

The French game of Tribord et Bâbord appears to be similar to Crown & Anchor, but the rules are very different.

References

Lynd, Robert (). It’s a Fine World. Methuen & Co.: London. hdl:2027/mdp.39015048888211.

Anonymous (). ‘Dissolution of Coronation Fair in Hyde Park’. The Statesman, : page 2. London, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘Curiosities of Medical Experience No. VIII’. Punch, or The London Charivari vol. 2: page 227. London, England.

Anonymous (). ‘Gambling at Fairs’. London Evening Standard, : page 7. London, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘Gambling at the Races’. Walsall Free Press and General Advertiser, : page 4.

Anonymous (). ‘The Mysteries of Edinburgh: Part I—Deacon Brodie, Chapter II’. North Briton, : page 4.

Anonymous (). ‘Easter Monday in the Forest’. East London Observer, : page 2. London, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘Gambling in Middlesbrough: A Visit “Down the Bank”’. The North-Eastern Weekly Gazette, : page 5. Middlesbrough, Yorkshire, England.

Teirlinck, Isidoor and Reimond Stijns (). Aldenardiana: Novellen Uit het Zuiden van Oost-Vlaanderen [text in Dutch]. Xavier Havermans: Brussels.

Anonymous (). ‘Lay of a Melbourne Vagrant’. Melbourne Punch, : page 6. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Public Business’. The Herald, : page 2. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Hong Kong’. Overland China Mail vol. 40 (817), : page 2.

Harding, Arthur and Raphael Samuel (). East End Underworld: Chapters in the Life of Arthur Harding. Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, England, UK. ISBN: 0-7100-0725-6.

Collier, Alfred (). ‘Games played with boards and dice’. Patent application 14,636. Filed Saturday, 29th August 1891.

Collier, Alfred (). ‘Means for Playing a New Game’. Patent GB190506544A. Filed Tuesday, 28th March 1905. Issued Thursday, 28th September 1905.

Young, David (). ‘An Improved Game, and Means for Playing the same’. Patent GB189504141A. Filed Tuesday, 26th February 1895. Issued Saturday, 16th November 1895.

Anonymous (). ‘“Crown and Anchor” Explained By A Policeman’. Melton Mowbray Mercury and Oakham and Uppingham News vol. 29 (1,157), : page 6. Leicestershire, England.

Graham, Stephen (). A Private in the Guards. Macmillan and Co: London, England, UK.

Partridge, Eric (). Smaller Slang Dictionary (2nd edition). Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, England. ISBN: 0-7100-1938-6.

Anonymous (). ‘Whitcombes Sale (advertisement)’. The Press vol. 77 (23,378), . Christchurch, New Zealand.

Hayes, Bertram (). Hull Down: Reminiscences of Wind-jammers, Troops and Travellers. The Macmillan Company: New York. hdl:2027/uc1.$b556318.

Anonymous (). ‘A Glimpse at Waterval Prison’. The Scone Advocate, : page 5. NSW, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Trooper Milverton Ford’s Escape’. The Sydney Morning Herald, : page 3. NSW, Australia.

Josling, Harold (). The Autobiography of a Military Great Coat: Being a Story of the 1st Norfolk Volunteer Active Service Company. Jarrold & Sons: London, England.

Johnson, L. H. (). The Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry Cavalry, 23rd Co., I. Y..

Anonymous (). ‘A new game from South Africa’. Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, : page 2. Hillingdon, London, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘Gambling In The Army’. Cobram Courier, : page 3. Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Robbing Tommy Atkins’. The Ottawa Citizen, : page 5. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Anonymous (). ‘The Drayton Grange’. The Sydney Morning Herald, : pages 7–8. NSW, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘From Tombs Baker warns boys against bad company’. The Pittsburgh Press, : page 29. Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Sutcliffe, Sam (). Nobody Of Any Importance. Sutcliffe & Son. ISBN: 978-0-9929567-2-1.

Brophy, John and Eric Partridge (). The Long Trail: What the British soldier sang and said in the Great War of 1914–18. Andre Deutsch: London, England.

Raby, G. S. (). ‘Jerry Wins a Bet’. Page 119 in 500 of the Best Cockney War Stories. Associated Newspapers: London, England.

Anonymous (). ‘An Interesting Narrative’. The Sun, : page 2. Christchurch, New Zealand.

Edwards, S. (). ‘At an English N.C.O. school’. Gisborne Times, : page 3. Gisborne, New Zealand.

Candler, Edmund (). The Year of Chivalry. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.: London. ark:/13960/t25b02s9t.

Jacobson, Gerald F. (). History of the 107th Infantry, U.S.A.. Seventh Regiment Armory: New York. doi:2027/mdp.39015027341364.

Breul, Harold (). 307 At Home and In France. Country Life Press. hdl:2027/wu.89066035734.

McAvity, Frederick Gerald (). ‘With The Ammunition Train’. Pages 91–95 in What the “Boys” did Overthere, by “Themselves”, edited by Henry L. Fox. The Allied Overseas Veterans Stories Co.: New York. ark:/13960/t2z32nv4t.

Rae, Herbert (). Maple Leaves in Flanders Fields. E. P. Dutton and Company: New York. ark:/13960/t9k35xv39.

Anonymous (). ‘Life on Transport Sardinia’. The Herald, : page 6. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

MacDonald, Frank Cecil (). The Kaiser’s Guest. Country Life Press.

Anonymous (). ‘A New Game’. Illawarra Mercury vol. 63 (16), : page 12. Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia.

Miller, James (). The Dam Builders: Power from the Glens. Birlinn: Edinburgh, Scotland. ISBN: 1-84158-225-5.

Dobree, C. T. (). Gambling Games of Malaya. The Caxton Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Culin, Stewart (). Chinese Games with Dice and Dominoes. Government Printing Office: Washington.

วงศ์ณาศรี, ปัณณพงศ์ [Pannapong Wongnasri] and นันธิดา จันทร์ศิริ [Nanthida Chansiri] (). พนันกับการบูรณาการหลักธรรมเพื่อแก้ปัญหาจากการพนันของชุมชน [text in Thai]. ศูนย์ศึกษาปัญหาการพนัน คณะเศรษฐศาสตร์ จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย: Thailand.

SEAlang (). ‘SEAlang library Khmer dictionary’. SEAlang.

SEAlang (). ‘SEAlang library Burmese dictionary’. SEAlang.

Anonymous (). ‘A Sensation at the Poona Races’. Madras Weekly Mail vol. 61 (15), : page 16. Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Anonymous (). ‘Emperor v. Hussein Noor Mahomed and Others’. The Indian Law Reports, Bombay Series vol. 30: pages 348–358.

Yunos, Rozan (). ‘Hua Hui and Gambling Games in Brunei’ [archived]. On the website The Daily Brunei Resources (accessed ).

SEAlang (). ‘SEAlang library Balinese dictionary’. SEAlang.

Low, Alfred M. (). ‘Sports and Pastimes in the West Indies’. The Windsor Magazine vol. 16: pages 689–695.

Manning, Frank E. (). ‘Celebrating Cricket: The Symbolic Construction of Caribbean Politics’. American Ethnologist vol. 8 (3), : pages 616–632.

Manning, Frank E. (). ‘Cup Match and Carnival: Secular Rites of Revitalization in Decolonizing, Tourist-Oriented Societies’. Pages 265–281 in Secular Ritual, edited by Sally F. Moore and Barbara G. Myerhoff. Van Gorcum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. ISBN: 90-232-1457-9. Van Gorcum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Macdonald–Smith, Ian (). A Scape To Bermuda.