Kōnane

Last updated: .

Kōnane (sometimes also called mū, which is also used to refer to draughts) is a traditional Hawaiian abstract game for two players. While it looks similar to checkers at first glance, the object of the game is different, and the strategy is very deep.

A game of kōnane in action.

2018 NPS/Janice Wei, 🅮

History

Kōnane stands alone as a purely-abstract game in Hawaiian culture.John F. G. Stokes (1875–1960, an Australian archæologist on Hawaiʻi) suggested at one point—with only a sliver of linguistic evidence—that Kōnane could be a distant descendant of Go, which had been transmitted by the survivors of Japanese shipwrecks.A However, it definitely existed before European contact, as it was described by Captain Cook’s voyage, which was the first of its kind to reach the islands (see below).

The game dates at least from the early 18th century, as it was played by Kahekili II (c. 1737–1794), who was high chief (aliʻi nui) of Maui. Kahekili and his advisers possibly used the board, or at least the pieces, to plan battles:

[T]here was no other king so genuinely accomplished in making war as King Kahekili of Maui and the actions on the battlefield plainly showed his knowledge of the checkers game of war. […] It was also said that at the house of Kahekili the heaps of little stones were maneuvered for battle strategy so that his generals need only fulfill their movements.B (p. 41)

Not only were [the old kāhuna of this land] seers, but some of them used the papa kōnane hoʻoneʻe ʻiliʻili [kōnane stones] to guide them in understanding the movements on the battlefield.B (p. 123)

The gods were also rumoured to enjoy kōnane: the volcano goddess Pele was said to play it at her home in Hale-maʻumaʻu crater.C (p. 183)

The earliest written record we have of the game is from James King,At the time of the entry quoted, Captain Cook himself had been killed. James King completed the official account of the voyage upon returning to England. who was an officer that sailed on board Captain Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific. In an entry dated March 1779, he wrote:

It is very remarkable, that the people of theſe iſlands are great gamblers. They have a game very much like our draughts; but, if one may judge from the number of ſquares, it is much more intricate. The board is about two feet long, and it is divided into two hundred and thirty-eight ſquares, of which there are fourteen in a row, and they make uſe of black and white pebbles, which they move from ſquare to ſquare.D (p. 144)

Another early witness was Archibald Campbell,Campbell arrived in Hawaiʻi aboard the Neva, the first Russian ship to circumnavigate the world, on the 29th of January 1809, and left aboard the Duke of Portland, a whaler, on the 4th of March 1810. The Duke of Portland also carried a letter from King Kamehameha to King George III, see Hackler (1986). More information about the ships is available in Jackson (1992). a Scottish sailor who visited Oʻahu from 1809–1810. In his book, he described the game:

They have a game somewhat resembling draughts, but more complicated. It is played upon a board about twenty-two inches by fourteen, painted black, with white spots, on which the men are placed; these consist of black and white pebbles, eighteen upon each side, and the game is won by the capture of the adversary’s pieces.

Tamaahmaah [King Kamehameha I, rumoured to be the son of Kahekili II] excels at this game. I have seen him sit for hours playing with his chiefs, giving an occasional smile, but without uttering a word. I could not play, but William Moxely [Campbell’s interpreter], who understood it well, told me that he had seen none who could beat the king.

The game of draughts is now introduced, and the natives play it uncommonly well.G (p. 145)

The area around where Kamehameha lived was called Kou, and was famous as being a location for playing kōnane.H (p. 8) A large stone kōnane boardLegends of old Honolulu indicates that the site of the large stone board was the “Spreckels Building”, which was on Fort Street between Merchant St and Queen St, and that the smaller boards mentioned were near Kekūanāoʻa’s house, which was on the corner of King and Richards Streets. was reported to be opposite the temple (marked “Hale o Lono” in the map below), in the current location of the Hawaii Community Foundation. Smaller boards were near what is now Iolani Palace.

A reconstruction of Honolulu as it was in 1810. Kamehameha lived in the large compound on the point at the bottom centre. Kou is the area around there, bordered by the yam field at the top. Archibald Campbell stayed for some time with Isaac Davis, who lived in the rightmost of the three houses on the left. (Map from the University of Hawaiʻi.)

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The game continued to be popular throughout the 19th century; William Brigham (first director of Hawaii’s state museum) reported that King Kalākaua (1836–1891) and his wife Queen Kapiʻolani (1834–1899) were “experts at konane”.I (p. 378)

In current times, it is a popular game during the Makahiki (new year) festival.J

Equipment

The Board

The board (papakōnane or papamū) is a square or rectangular grid of pits (lua). Traditionally, boards were carved out of wood and raised slightly off the ground for ease of play, or were made by scraping holes into a slab of volcanic rock. Games could also be played on the squares of a woven lauhala mat.K (p. 85)

Stone boardsPeter Faris’ ‘Rock Art Blog’ has pictures of several stone boards. can be found all over the islands of Hawaii, whereas traditional wooden boards are now hard to find, and are mostly restricted to museums.An image of a traditional carved board from Iolani Palace can be seen in this Hawaiʻi Magazine article. In November 2017, an antique wooden board with shell inlay sold at auction for €150 000. Wooden boards sometimes had a human molar inset in the central hole (piko, ‘navel’), or in some cases in all the holes of the board.L

Historical board sizes vary greatly, and there is no standard size. King’s account implies a board of 14×17 squares, while Campbell’s account implies a 6×6 board. An archæological survey on the island of LanaiK (p. 84) found 14 boards, with sizes ranging from 8×8 to 13×20.The complete list of sizes found by Emory’s team was: 8×8, 8×11, 8×13, 9×10 (2 boards), 9×13 (2), 10×10, 11×11, 11×13, 13×13, 13×15, 13×20, and 15×15. Peter Buck shows two 12×15 boardsOne of the boards shown by Peter Buck is also shown by Culin.M from the Bishop Museum.L

Peter Buck also describes another board in the Bishop Museum which has 10 rows that alternate in length between 6 & 7 holes.L This seems to be the same board described by Emory, where the pits are set quincuncially.K (p. 84) This is probably not a board for playing kōnane, but for playing a game similar to damas (‘Spanish draughts’), which is known in Hawaii as mū. However, it could also be used to play kōnane by playing the game on the diagonal.

A kōnane board at Alahaka Bay.

© 2017 Deb Nystrom, 🅭🅯

The Pieces

The game is played with black & white pebbles (ʻiliʻili); often the black pieces (ʻiliʻili ʻeloʻelo) were basalt and the white pieces (ʻiliʻili keʻokeʻo or kea) made of branch coral.C (p. 159) One wahi pana (celebrated location) for stones was Kōloa,Kōloa was also famous for its reproducing stones (ʻiliʻili hānau). For more about these, see Beaches of the Big Island or Majestic Kaʻū: Moʻolelo of Nine Ahupuaʻa. a beach situated between Nīnole and Punaluʻu in Kaʻū on Hawaiʻi.C (p. 258) Unfortunately most of this beach has been stripped of its stones for (unrelated) commercial purposes.N (p. 62)

Acquiring a set

Commercially produced boards are readily available in Hawaii or online. They are often wooden, with black and white glass pieces. You can also play the game on a beach, using rocks or shells in contrasting colours.

Play

The board is set up by filling it with black and white pieces in a checkerboard pattern.

A kōnane board ready to play.

© 2016 Kris Arnold, 🅭🅯

To begin, the first player removes a piece from the centre of the board (or one of the squares adjacent to that, on an even-sized board), or from any corner. The second player removes a piece adjacent to the first, and play commences with each player moving the pieces of the colour that they removed.

On their turn, a player must move a single piece by jumping it over an orthogonally-adjacent enemy piece into an empty hole, thereby capturing the enemy piece and removing it from the board. A piece may also make multiple captures in the same direction by jumping multiple times – this is called kāholo, ‘to move quickly’.

The first player that cannot move any piece on their turn loses; draws are not possible.

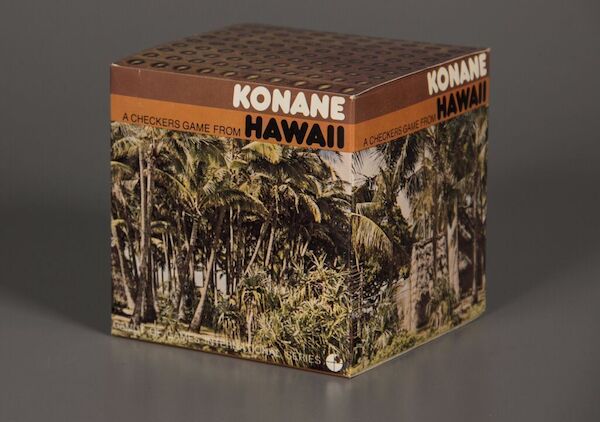

A commercial version of kōnane. The board can be seen on the top of the box.

Analysis

Michael Ernst has performed game-theoretic analysis of various board positions.P Analysis of techniques for AI play has been done by Teaching a Neural Network to Play Konane and Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Konane.

See also

Take It Away and Leap-Frog play similarly but have different winning conditions.

References

Stokes, John F. G. (). ‘Japanese cultural influences in Hawaii’. Pages 2791–2803 in Proceedings of the fifth Pacific Science Congress volume 4. Pacific Science Congress: Vancouver, BC, Canada. Pacific Science Congress: Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Desha, Stephen L. (). Kamehameha and his warrior Kekūhaupiʻo. Kamehameha Schools Press: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi.

Ellis, William (). A Narrative of a Tour through Hawaii, or Owhyhee; with remarks on the History, Traditions, Manners, Customs and Language of the Inhabitants of the Sandwich Islands. Hawaiian Gazette Company: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. ark:/13960/t3st7f903. First published in 1827.

King, James (). A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean volume 3. W. and A. Strahan: London, England, UK. ark:/13960/t7mp54w69.

Hackler, Rhoda E. A. (). ‘Alliance or Cession? Missing Letter from Kamehameha I to King George III Casts Light on 1794 Agreement’. The Hawaiian Journal of History vol. 20: pages 1–12. hdl:10524/548.

Jackson, Frances (). ‘The Duke of Portland, the Traveller, and the Prince Regent: Three Little-known Vessels from Australia’. The Hawaiian Journal of History vol. 26: pages 45–54. hdl:10524/200.

Campbell, Archibald (). A Voyage Round the World. Van Winkle, Wiley & Co.: New York, NY, USA. ark:/13960/t7fr00v6f.

Westervelt, William Drake (). Legends of old Honolulu. Press of Geo. H. Ellis: Boston, MA, USA.

Brigham, William Tufts (). The Ancient Hawaiian house; Memoirs of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum of Polynesian Ethnology and Natural History volume 2, number 3. Bishop Museum Press: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. ark:/13960/t9d513m88.

Ahles, Jessica (). ‘Konane: A Game Played, Value Won’. The Molokai Dispatch, .

Emory, Kenneth Pike (). The island of Lanai: A survey of native culture; Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletins number 12. Bernice P. Bishop Museum: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. hdl:2027/miun.arf6076.0001.001.

Buck, Peter (). Arts and Crafts of Hawaii. Bishop Museum Press: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. ISBN: 1-58178-027-3.

Culin, Stewart (). ‘Hawaiian Games’. American Anthropologist vol. 1 (2), : pages 201–247.

Clark, John R. K. (). Beaches of the Big Island. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN: 978-0-8248-0976-8.

Kelly, Marion (). Majestic Kaʻū: Moʻolelo of Nine Ahupuaʻa. Bernice P. Bishop Museum: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi.

Ernst, Michael D. (). ‘Playing Konane mathematically: A combinatorial game-theoretic analysis’. UMAP Journal vol. 16 (2): pages 95–121.

Thompson, Darby (). Teaching a Neural Network to Play Konane [archived]. Bryn Mawr College: Bryn Mawr, PA, USA.

Hendrick, Kaitlin (). Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Konane [archived]. Honors Thesis, Texas Christian University: Fort Worth, TX, USA.