Morabaraba

Last updated: .

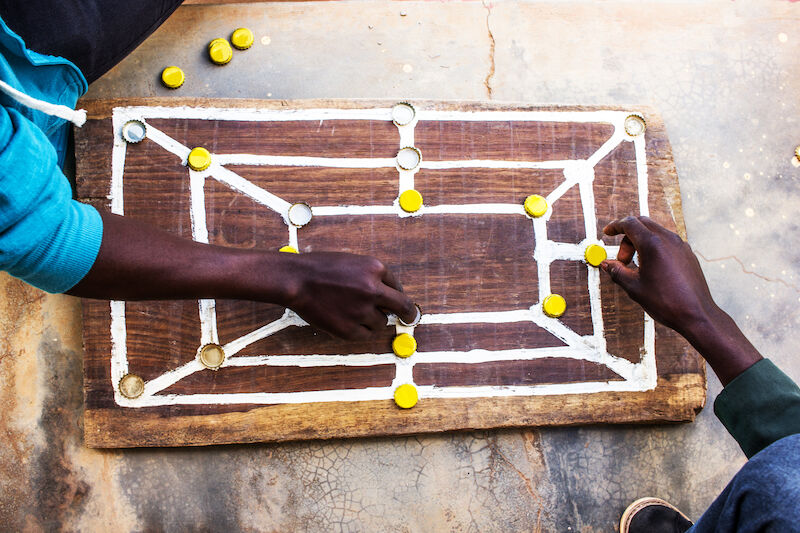

Morabaraba is a popular mill game from south-eastern Africa.

Morabaraba is played across south-eastern Africa.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The gameplay of the standardized version is very similar to Twelve Men’s Morris (with a few minor differences), but the version played in Lesotho has a unique board.

Morabaraba is played as a competitive sport in South Africa, administered by Mind Sports South Africa. It is widely played throughout the country; a poll conducted by The Sowetan in 1996 indicated that 40% of South Africans played the game.A

A game of Morabaraba being played.

History

Surprisingly, unlike most board games we know who was responsible for transmitting the game from Europe:B (p. 134)C (p. 79) it was introduced to Lesotho—then called Basutoland—some time between 1832 and 1855 by Eugène Casalis, a French protestant missionary who acted as Foreign Advisor to King Moshoeshoe I for nearly two decades.Casalis is also sometimes also referred to as Cazalis in English sources. Upon his return to France he wrote about his experiences in Les Bassoutos ou Vingt-trois années de séjour et d’observations au sud de l’Afrique (later published in English as The Basutos; or, Twenty-Three Years in South Africa), but the book contains no mention of any board games. There is now a roundabout in his home town, Orthez, named after him. The introduction of the game had unintended consequences for the mission: young men preferred to play the game rather than attend mass.C (p. 79) Obsession with the game also led herders to neglect their flocks,C (p. 79) so it became known by the epithet sethetsabadisana ‘deceiver of the herd-boys’:F (p. 41) “for when you play it, old or young, you forget your herds, and they wander into the corn…”G (p. 56)

The game was also popular amongst Basotho men who travelled to South Africa to work in its mines. References to Morabaraba can be found in difela/lifela (singular sefela), song–poems that were sung by these migrant workers.H (pp. 17, 175, 229)I (pp. 98–101)

In Lesotho’s past the game was restricted to being played by men, to the point that women were not permitted in the vicinity of the gaming area.J (p. 95) Thankfully, times have changed, and as of 2021, the top-ranked player in Mind Sports South Africa’s league is a woman, named Saudah Bhaimia, who has won the last three national championships.K

Casalis was stationed at Moshoeshoe’s stronghold Thaba-Bosiu, which was positioned atop a sandstone plateau.

Terminology

The name moraba-raba comes from the Sesotho language, and is related to the verb ho raba raba ‘to roam in small circles’,M (p. 304) so could refer to the action of a mill. In Nguni languages (isiZulu, isiXhosa), it is known as (Um)labalaba, with similar meaning,N (pp. 247–50) and in Ronga, spoken in Mozambique, it is called Muravarava.

Two Lesotho herdsmen carrying staffs. What appear to be caps are rolled-up balaclava: most of Lesotho is above 1 800 m, so it is cooler than many neighbouring countries.

There are other names which are probably derived from the European name of ‘mill’:B (p. 134) an alternate Sesotho name is mmila/’mila, ‘road’.O (p. 283) This is also sometimes given as mmela.P (p. 378)

In some places, the name morabaraba refers solely to a mancala game, and the board game goes by other names. This is the case in Botswana,Q where it is called mohele or mhele in Setswana (‘reedbuck’R (p. 350) or ‘grey rhebuck’,S (p. 92) a type of antelope), and also the neighbouring South African province Limpopo, where it is called mmela (possibly in sePedi).Because of the large overlap of names, in written descriptions Morabaraba is often confused with or included in lists of other mancala games, such as mefuvha (from Limpopo) or tsoro (from Mozambique/Zimbabwe) (see, for example, [A]). In other places, the same name is used to refer to both the board game and the mancala game; the Lozi people refer to both as mulabalaba.T (170)

A distinctive feature of this game is its bovine theme: the pieces are usually called ‘cows’. In Sesotho this is dikgomo/likhomo (singular kgomo/khomo);U (p. 588) in isiZulu it is izinkomo (singular inkomo). In isiZulu a mill is a isibhamu (‘gun’), which allows you to “shoot” an opponent’s cow, while in Sesotho the mill is called a molamu (a staff carried by shepherds), and you can eat (ja) a cow.F (p. 36)

Play

The following description is based on Mind Sports South Africa’s “Generally Accepted Rules”. As with all traditional board games, local rules can vary.

Each player has 12 pieces. Commonly, plastic or metal bottle capsThe use of bottle caps is so common that even commercial sets use bottle caps, and they show up in computerized versions as a skeuomorphic feature. are used in two contrasting colours.

Standard Morabaraba is played on the large mill board with diagonals.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

During the placement phase, players must place a single piece on any vacant point of the board. Once all their pieces are placed, players can move a single piece to another vacant point, along one of the lines.

If a player places or moves a piece to form a new mill, they remove one of the opponent’s pieces. The removed piece may not be from a mill unless there are no other pieces that can be removed.

During the placement phase it is possible to form two mills at once. In Morabaraba this only allows a player to remove one piece.

When a player is reduced to three pieces, their pieces can ‘fly’ and move to any vacant point on the board, ignoring the lines.

A player loses the game when they are reduced to fewer than three pieces, or if they are unable to make a valid move on their turn.

A game of Muravarava being played in Mozambique, at Chinhamapere Secondary School.

© 2018 Shutterstock.com/ivanfolio

In tournament play, Mind Sports adopted an additional rule: During the movement phase, a piece that is moved from one mill to form another mill may not move back to form a mill again at the original point on the next turn. Instead, a different move must be taken before doing so. This rule prevents a player from moving backwards and forwards between two mills quickly. This rule seems to me to be unlikely to be used in casual play.

Analysis

With perfect play, the first player can force a win in 49 moves.V

Variants

Sotho version

The Sotho version of the game is played on a board with a central cross.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The Sotho version of the game is played on a special board or flat stone (letlapa)F (p. 35) where the centre square is also crossed, and the inner diagonals are missing, giving 25 points that can be played on.WB (p. 133) This means that there is no possibility of a deadlock after the placement phase.

The centre of the board is called the hole (koti)X or well (diba).F (p. 40)

Most rulesets state that a piece on the central point can only be the middle piece of a mill. Other lines of three formed with the central point do not count as mills.YZ (pp. 67–70) Note also that it is not possible to form a diagonal mill on this board.

Mosimege (2006, p. 16) reports that the game ends as soon as one player is reduced to 3 pieces, rather than 2.

Strategems

In Lesotho, there are some well-known strategems (mawa/maoa, singular lewa/leoa) that have been named:

ka selibeng ‘using the well’, khomo ea koti ‘cow in the hole’: to start the game by placing a piece in the middle of the boardX

chitja/tjhitja ‘round’, also meaning a cow without horns: to completely surround the opponent so that they cannot move, a winning strategyXF (p. 40)

khutla/kgutla ‘return’, a “running mill” which can be formed and reformedXB (p. 134)F (p. 40)

mapeli ‘two’, semufu (?), or thwenthwere/thoenthoere (onomatopœic): to form two mills at the same time (in a corner)XF (p. 40)

There are also others that I have not been able to figure out; see the sources linked above.

Some examples of valid mills on the Sotho board.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Not a mill; any mill using the centre point must have its middle piece on the centre point.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

A Sotho-style morabaraba board in Kliptown, Soweto (more examples of this board can be seen on Instagram: 1, 2, 3, 4).

© 2012 Nagarjun Kandukuru, 🅭🅯🄏⊜

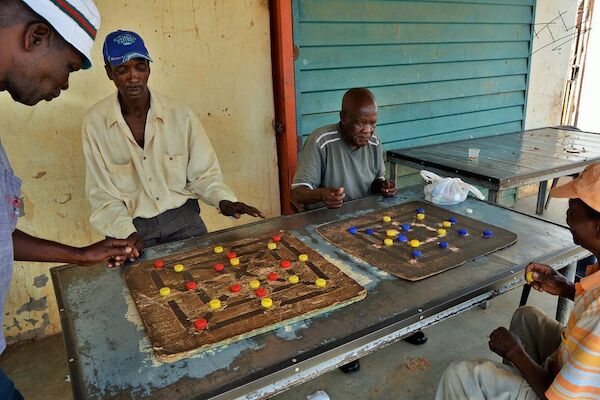

Alternate board

An alternate Morabaraba board.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Another board pattern is also used to play Morabaraba, with a diagonally crossed central square. I do not know if the rules vary in any way.

Men playing on a different Morabaraba board. More examples of this board can be found on Instagram: 1, 2.

© 2017 mk11photography , used with permission

References

Russouw, Sheree (). ‘Getting morabaraba back on board’. On the website City of Johannesburg.

Mkele, N. (). ‘A Note on “Bantu Games”’. Journal of the National Institute for Personnel Research vol. 6 (3): pages 132–134.

Mosimann–Barbier, Marie-Claude (). From Béarn to Southern Africa, or the Amazing Destiny of Eugène Casalis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, England, UK. ISBN: 978-1-4438-5665-2.

Casalis, Eugène (). Les Bassoutos ou Vingt-trois années de séjour et d’observations au sud de l’Afrique. Ch. Meyrueis et Cie: Paris.

Casalis, Eugène (). The Basutos; or, Twenty-Three Years in South Africa. James Nisbet & Co.: London.

Masiea, Joshua Rawley (). The Traditional Games of Basotho Children. Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa.

Mopeli-Paulus, Atwell Sidwell (). The World and the Cattle. Penguin: South Africa. ISBN: 978-0-14-318557-4.

Tšiu, William Moruti (). Basotho oral poetry at the beginning of the 21st century volume 1. PhD thesis, University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa.

Coplin, David B. (). In the time of cannibals: the word music of South Africa’s Basotho migrants. The University Of Chicago Press: Chicago.

Turner, Stephen D. (). Sesotho farming: the condition and prospects of agriculture in the lowlands and foothills of Lesotho. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Mind Sports South Africa (). ‘Saudah Bhaimia (Curro Klerksdorp) leads the pack’ [archived]. On the website Esports, and other games (accessed ). Mind Sports South Africa.

Bennett, John and Nthuseng Tsoeu (). Multilingual Illustrated Dictionary: English, IsiZulu, Sesotho, IsiXhosa, Setswana, Afrikaans, Sepedi. Pharos Dictionaries: Cape Town, South Africa. ISBN: 978-0-7021-6712-6.

Mabille, Adolphe and E. Jacottet (). Se-Suto–English and English–Se-Suto Vocabulary. Khatiso: Moria, Limpopo, South Africa.

Ntšihlele, Flora Mpho (). Games, Gestures and Learning in Basotho Children’s Play Songs. PhD thesis, University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa.

Nkopodi, Nkopodi (). ‘Using Games To Promote Multicultural Mathematics’ [archived]. Pages 283–287 in Proceedings of the International Conference on New Ideas in Mathematics Education, edited by Alan Rogerson. Mathematics Education into the 21st Century Project: Palm Cove, Cairns, Australia. Mathematics Education into the 21st Century Project: Palm Cove, Cairns, Australia.

Nkopodi, Nkopodi and Mogege Mosimege (). ‘Incorporating the indigenous game of morabaraba in the learning of mathematics’. South African Journal of Education vol. 29: pages 377–392.

Garegae-Garekwe, Kgomotso Gertrude (). Cultural games and mathematics teaching: a study of teachers in Botswana. Master’s thesis, University of Alberta: Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. doi:10.7939/R3GQ6RB47.

Cole, Desmond T. (). ‘Old Tswana and new Latin’. South African Journal of African Languages vol. 10 (4): pages 345–353. doi:10.1080/02572117.1990.10586868.

Snyman, J. W., J. S. Shole, and J. C. Le Roux (eds.) (). Dikišinare ya Setswana–English–Afrikaans [text in Tswana]. Via Afrika: Pretoria, South Africa. ISBN: 0-7994-1218-X.

Chaplin, J. H. (). ‘A Note on Mancala Games in Northern Rhodesia’. Man vol. 56, : pages 168–70.

Moloi, Tshele J (). ‘The Use of Morabara Game to Concretise the Teaching of the Mathematical Content’. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences vol. 5 (27): pages 585–591. doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p585.

Gévay, Gábor E. and Gábor Danner (). ‘Calculating Ultrastrong and Extended Solutions for Nine Men’s Morris, Morabaraba, and Lasker Morris’. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games vol. 8 (3): pages 256–267.

Sport and Recreation South Africa (). Indigenous Games Rule Book. Sport and Recreation South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa.

Khoro, Tšepo (). ‘Papali ea Moraba-raba’ [text in Southern Sotho] [archived]. On the website Slideshare (accessed ).

Powe, Edward L. (). ‘What is Umlablaba?’ [archived]. On the website BLAC Foundation (accessed ).

Zaslavsky, Claudia (). Tic Tac Toe and other three-in-a-row games from Ancient Egypt to the modern computer. Thomas Y. Crowell: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 0-690-04317-1.

Mosimege, Mogege (). ‘Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Ethnomathematics’. In Third International Conference on Ethnomathematics. Auckland, New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand.