白鴿票 · The Pigeon Lottery

Last updated: .

The Pigeon Lottery (白鴿票/白鸽票 Cantonese: baak⁶ gaap³ piu³) is a gambling game that originated in Guangdong during the late Qing dynasty, and which in the 19th and 20th centuries was spread throughout countries bordering the Pacific Ocean by Chinese emigrants.

The recent history of the game is often a story of racism and hypocrisy: as a Chinese gambling game, Chinese migrants were punished for running the game while at the same time gambling games favoured by Europeans were permitted. In the 20th century the game was adapted by Americans who profited from a now-legal game even as the Chinese game was suppressed. Eventually the game became known under the modern name of Keno, which is now played in casinos around the world.

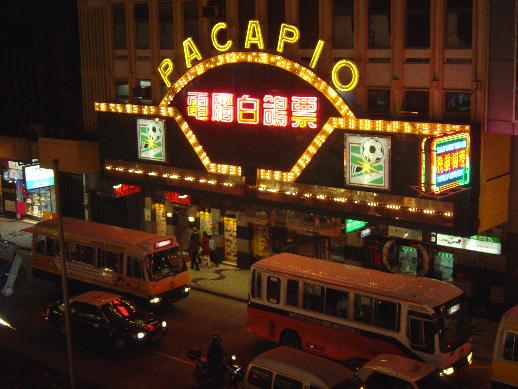

In European sources, the game is often referred to as simply “the Chinese lottery”. The transliteration of the game is usually given as “pak-a-poo” (most common in New Zealand) or “pak-a(h)-pu” (most common in Australia). In London (particularly centred around the Chinese community in Pennyfields, Poplar) it was referred to as “puk-a-pu” or “puk-a-poo”, and in South Africa “pa-ka-pu”.E (p. 423) Other variants are “pak-a-peu”,F “puck-a-pu”, “pukka-poo”, or “pac-a-poo”. In Macau it is given with the Portuguese romanization of “pacapio”, which remains standard in current usage (previous terms include p’u-pioG). In the USA it was at first referred to as “boc hop bu”H before picking up a variety of the other names mentioned above, as well as “Bock Ka Pian”,I but in Hawaiʻi it was referred to as “pakapio”.J

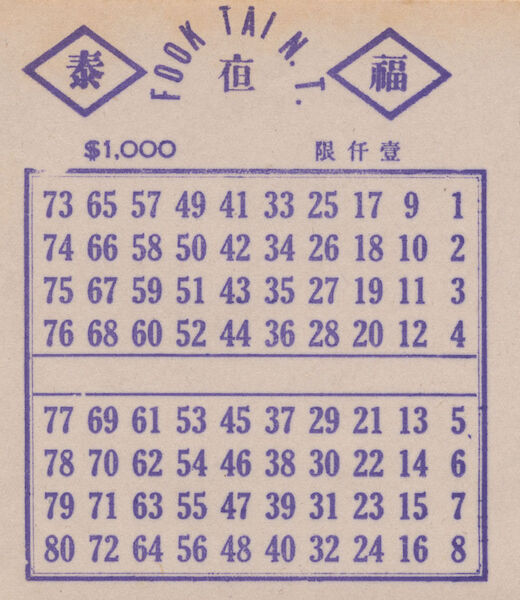

While the specifics vary, the play of the game is simple: each player purchases one or more tickets upon which they mark some set of characters out of the eighty that are printed on the ticket. The seller or “bank” then randomly selects a given number of characters, and players win money according to the number of matching characters they have marked on their ticket. The specific numbers of characters chosen and the permissible bets vary by both time and location.

In many locations the game was treated as illegal, running afoul of anti-lottery laws; this despite it not being a lottery.See, for example, Gambling Games of Malaya (p. 48): “although this form of gambling is named in the Chinese as ‘Lottery’, there is doubt that it is in fact a ‘lottery’. In a lottery there is a distribution of prices (usually money) by chance or lot. But in this form of gambling there are no prizes in the accepted sense, and although money paid out by a promoter to lucky punters is dependant on numbers drawn by chance, that money is not a distribution of prize money, but is in fulfilment of betting contracts.” Even when it started to become popular in American casinos, many Keno writers (ticket markers) believed it to be a lottery, and that it had only become quasi-legal through subterfuge (for example, see A Family Affair: Harolds Club and the Smiths Remembered (p. 179), and many other examples stating it to be a lottery).

Early origins

It is sometimes fancifully claimed that the name of the game is due the the method of ticket selection, in that supposedly originally white pigeons were used to choose winning tickets, but that is not possible given the way the game is played; it is not a lottery where one or more tickets are selected to be winners.

One Chinese origin story says that the name is because white pigeons were used to transmit the results from gambling houses to the bettors.L (p. 157) Another dates the game to the foundation of the Han dynasty, saying that it was invented by Zhāng Liáng (張良, c. 251–189 BCE),Older sources transliterate his name as Cheung Leung. advisor to Emperor Gāozǔ, in order to raise money for the support of the army when a city was beseiged.L (p. 156) While Zhāng Liáng may have really used a lottery to raise funds, it seems to be unlikely to be identical to the modern game. For one thing, the Thousand Character Classic upon which the game is based is traditionally dated to the Liang dynasty (502–557 CE).

The true origin of the game apparently lies in gambling that was carried out as part of the early-Qing “white pigeon festival” (白鴿會 Cantonese: baak⁶ gap³ wui²) which was held in Guangdong. Pigeons were raced from Qingyuan (清遠) to Foshan (佛山), and groups of pigeons were numbered using the opening characters from the Thousand Character Classic (千字文).This system of enumeration has also been used to number volumes of books and other objects, including in the instructions for assembly kit-set furniture.M (p. 53) Bets were made on which group of pigeons would return intact.N (p. 84) Eventually the pigeons were dropped entirely and a game was developed based on characters being drawn at random.

Known history

According to the Draft History of Qing,O the official Qin Ying (秦瀛, 1743–1821) banned pigeon tickets in Guangdong in the “ninth year of Jiaqing” (1804/5), so the game must have existed at this point.D

In 1849, a traveller from Yunnan province visited Guangdong and reported that:

In the western part of the provincial capital Guangzhou, people in Henan area developed cunning ways to operate the “white pigeon” lottery. Even women and children were addicted to the game. The former governor of Guangdong considered the “white pigeon” lottery to have been going out of control so he prohibited it. When this governor got promoted and left, the trend of playing the lottery came back.N (p. 64)

In the late 19th century, the game was also known as xiǎowéixìng 小闈姓 ‘small surname guessing lottery’,N (p. 85) after the main wéixìng 闈姓 ‘surname guessing lottery’, which was based upon guessing the surnames of people who passed the imperial service examinations.

What is known for certain is that it was first legalized in Macau by João Maria Ferreira do Amaral (1803–1849), who authorized the game in January 1847 upon the request of local Chinese businessmen.P (p. 110) Macau had been declared a free port in 1845, hoping to increase trade and business under competition from the recently-established British colony at Hong Kong (1842). Despite this, Macau was still in decline and Amaral was under pressure to raise revenue. Attempts by Amaral to introduce new taxes were unpopular and had even led to an armed revolt in October 1846. Thus, a system was devised whereby monopoly rights for important goods (including pork and beef, fish, salt, oysters and opium) were sold or auctioned off. Gambling monopolies were a logical extension of this idea.

The Macau Senate were unhappy with a number of the decisions made by the governor, and complained directly to Lisbon that, among other things,

… the Chinese were given license to operate lotteries inside the city, a thing that the same Government which allowed it had just two months before forbidden as immoral and harmful to peacefulness and public tranquillity.P (p. 110)

Nevertheless, the game was permitted to continue and licenses to run pacapio began to be issued on an annual basis from April 5, 1848. The game is still played today in Macau, but it is not very popular.A study in 2019 found that only 4 out of 855 gamblers (0.5%) had played the game in the last 12 months.Q

A “Pacapio” sign in Macau.

© 2005 Brian Chow, 🅭🅯

Back in Guangdong, the game was made legal in 1900 under similar terms, with the Hongyuan company (宏遠公司) winning the contract for the first four years for a total contribution of 3.6 million yuan.This source says “dollars” but yuan is intended, comparing with his original paper 何 (1995, 527).S (8) Other syndicates made competing offers, which eventually resulted in the transfer of the rights to a syndicate which offered better terms, only for that syndicate to collapse after it was unable to meet its obligations. The rights reverted to the Hongyuan company, but in 1904 the company did not attempt to renew the franchise due to the difficulty of meeting payments, and the incoming governor Cen Chunxuan reinstated a ban on the game from May 1904.S (8)

The Game

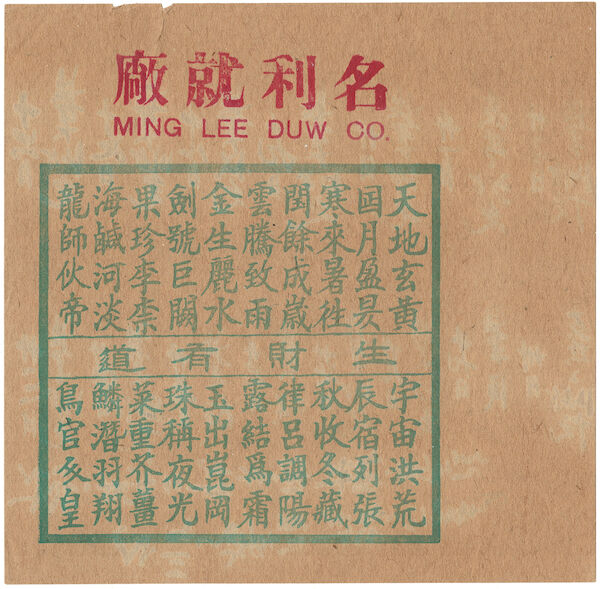

The primary artifact of the game is the ticket, a slip of paper upon which is printed the name of the bank (see below) and 80 unique Chinese characters. These characters are the first 80 taken from the Thousand Character Classic (千字文), and are always printed in a top-down, right-to-left order, broken into four-character blocks:

天地玄黄 宇宙洪荒

囸月盈昃 辰宿列張

寒來暑徃 秋收冬藏

閠餘成嵗 律呂調陽

雲騰致雨 露結爲霜

金生麗水 玉出崑岡

剣號巨闕 珠稱夜光

果珍李柰 菜重芥薑

海鹹河淡 鱗潛羽翔

龍師伙帝 鳥官人皇

A striking thing about this layout is just how consistent it was across all countries where the game was played. A ticket as used in Nevada was almost identical to one used in Victoria (Australia) or Otago (New Zealand). Tickets were printed locally,The National Library of New Zealand has at least 10 pakapoo printing blocks, and another photo documents the movement of a printing press that was originally used by one Joe Quinn to print pakapoo tickets in Wellington. as well as exported from China to other countries.See, for example, this ticket which is explicitly printed “Made in China”. Other tickets show evidence that the bank name was stamped onto the ticket at some stage later than the character grid was printed. Stewart Culin also describes how tickets were shipped from China in “large quantities”.B (p. 7) Tickets often bore the phrase 照來原底給 “printed according to the original”, so fidelity to the ideal form of the ticket was apparently sought-after.

A Ming Lee Duw Co. ticket from California (reading 名利就廠 right-to-left). The center reads 生財有道, a four-character idiom meaning “an expert in making money”, a reference to an extract from the Confucian Book of Rites.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The place that distributed the winnings and collected the profits was invariably referred to as the “bank”, and each bank would have its own name. In places such as California, where tongs (堂) were established, the banks would often be tied to a particular tong.T (p. 8) Guidebooks such as Essentials of the Lottery (票圖撮要, 1894) were also published, instructing prospective bank owners how to calculate payouts for various forms of tickets.

To play the game, a player would take a blank ticket, mark ten characters of their choosing, and then register their ticket with the bank. The bank would make a copy of the player’s ticket to ensure the security of the draw. Later, at a specified time, twenty numbers would be drawn, and any registered tickets with at least five matching characters be paid out at their specified rates (for which, see below).

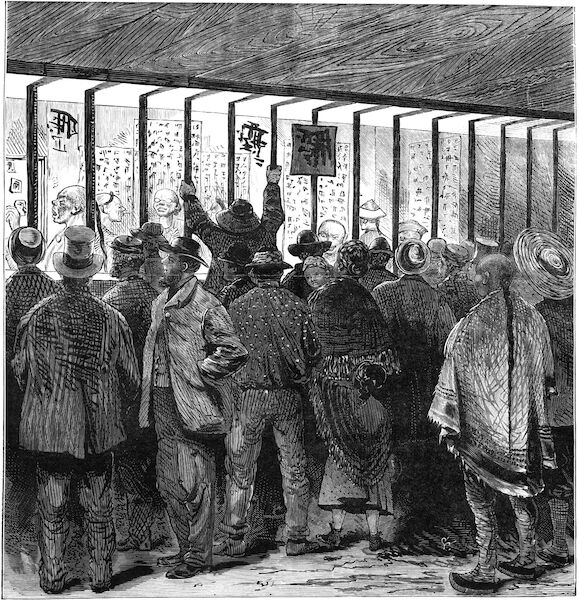

There were different methods for selecting the winning numbers. The drawing of numbers was performed publicly to assure bettors that the game was fair. A Sydney newspaper report of a court case from 1886 gives the following method:The same method is described in Melbourne in 1876.U (p. 7) 80 pieces of paper with one character each were rolled up and then mixed in a jar. From this jar, the pieces of paper were divided into four bowls, giving 20 tickets per bowl. Next, four pieces of wood engraved with a character each and then wrapped in paper (to hide the characters) were randomly placed, one in each bowl. Four pieces of paper with matching characters were rolled up and presented to an onlooker, who selected one, and then the wooden pieces were unwrapped to reveal their characters and find the matching bowl. The 20 winning numbers from this bowl were then read out.V

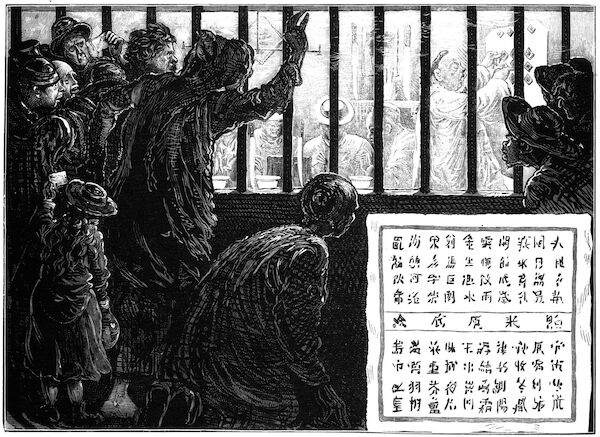

The area where the tickets were to be drawn, and where the bank’s capital was kept, was usually separated from onlookers by wooden bars. European descriptions and depictions often mention or show long knives that were kept behind the bars to defend against any attempts upon the bank’s chest (see, e.g. the image on the right below).

Drawing of tickets (Australia, 1873).W

Drawing of tickets, with a rather mangled representation of a ticket (Australia, 1876).U

In some Chinese versions of the game, there were restrictions imposed upon which characters could be drawn: ten had to be chosen from each of the upper and lower halves of the tickets, the whole four characters in a particular line, or four in a block or diagonal could not be selected at once (it is not stated how these restrictions were enforced).N (p. 104) These rules would allow the players to feel like they were able to have more control by making informed selections of characters.

Another feature that was sometimes used that allowed players to feel like they had some control over the game was the book called the “character container” (字容), which recorded the number of times each character had been drawn in the recent past.N (p. 102) In reality, this would function similarly to a Roulette tote board which displays the most recent results, and thus play up the effect of the gambler’s fallacy on the players.

Example payoff schemes

Below are a sampling of payoff schemes, to give a taste of the ratios used. The payouts vary based upon the number of correctly-chosen characters, in the left column:

Australia | New Zealand | New Zealand | Montana | Malaya | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

cost | 3厘 (cash) | 6d | 6d | 6d | 6d | 25¢ | $1 | 60¢ |

5 | 5厘 (cash) | 1/2 | 1/– | ? | 6d | 50¢ | $1 | $1.20 |

6 | 5分 (candareen) | 9/– | 8/6 | ? | 18/6 | $4.5 | $10 | $12 |

7 | 5錢 (mace) | £3 18/6 | £3 10/– | £4 | £3 15/– | $45 | $100 | $90 |

8 | 2兩 (tael) 5錢 (mace) | £20 15/– | £19 2/6 | £20 | £18 10/– | $225 | $625 | $660 |

9 | 5兩 (tael) | £36 | £35 | £40 | £36 | $450 | $1250 | $2400 |

10 | 10兩 (tael) | £70 | £70 | £80 | £85 | $900 | $2500 | $12,500 |

H.A. | 33.10% | 29.89% | 36.40% | — | 17.46% | 26.72% | 58.01% | 25.01% |

The trend over time has been to increase the payouts on the higher end, which makes the game more attractive to players while not unduly affecting the house margin — as long as the house has sufficient capital to avoid going bankrupt when a player hits a big win. Aggregate payout limits are also used to prevent such an occurrence; for example, a casino might advertise a $50,000 limit, which is the maximum combined winnings that players can win on any single game (bigger winners being paid out first).

Spread to other countries

Countries where the game was played in the past (before becoming Keno); locations with particular reports highlighted.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The game traveled everywhere that Chinese people migrated to. In particular, it seems to have been popular in places with goldfields where Chinese men came to work in the late 19th century: San Francisco in the USA, British Columbia in Canada, Victoria in Australia, and Otago in New Zealand.

Despite the existence of other very similar games in China, such as the ‘mountain lottery’ (山票 Mandarin: shān piào, Cantonese: saan¹ piu³), the pigeon lottery was the only one that was successfully popularized amongst Europeans.N (p. 193) Conversely, in countries such as Malaya, where the game was legal during the Japanese occupation (1941–42), the pigeon lottery was apparently never as popular as Chee Fah or Chee Tam (games based upon selecting one out of 36 or 80 characters, respectively).A (p. 48)

In the United States

According to Encyclopedia of Keno, the game was introduced to the Western United States in the mid-19th century, and had reached the Eastern cities by 1870.

Mentions of “Chinese lotteries” begin to appear in Californian newspapers from the 1860s, and sometime around 1863 Mark Twain mentioned the game in a report for Nevada’s Territorial Enterprise, noting its popularity in that “about every third Chinaman runs a lottery”, and that “we could not see that these lotteries differed in any respect from our own… the manner of drawing is similar to ours”.AB (p. 396)

The view that many Chinese immigrants were involved in lotteries was not only one coloured by European eyes; LiangQichao (梁啟超, 1873–1929), who visited Canada and the United States between 1899 and 1903, claimed that almost every Chinese family was involved with gambling in some way.N (p. 191)

According to Stewart CulinB (p. 11), by 1886 four banks were operating in PhiladelphiaHe provides the names “Extensive Increase” (廣泰 gwong² taai³), “Heavenly Harmony” (天和 tin¹ wo⁴), “Fortunate Increase” (福泰 fuk¹ taai³), and “Encouraging Fountain” (釗泉 ciu¹ cyun⁴). and five in New York, along with others in Boston and Chicago.

There were ten Chinese lottery banks operating in San Francisco in 1890,AC (p. 450) and by 1892 the same number operating in New York.AD In 1893 a report from the San Francisco Chief of Police stated that the police had in their possession 22 tons of blank lottery tickets which had been confiscated during the previous 13 years;AE (p. 150) by 1898 this had risen to 26 tons.AF (p. 173)The police were occasionally (and unsuccessfully) sued for the repossession of these tickets.

By the time Liang Qichao visited the United States in 1903, he estimated that one in ten of the Chinese immigrants in the large cities worked in gambling houses.N (p. 191)

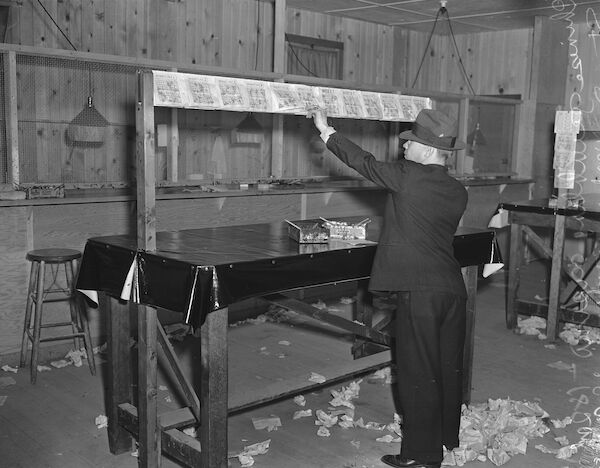

Interior of a Chinese lottery & casino in California, 1938, during a police raid. Ink and brushes are provided to mark the chosen numbers, and on the floor lie discarded losing tickets.

In Seattle, some known banks known in the 20th century were named: Union, N.P., Shanghai, New American, and Wing Tien.AG During World War II, the army forced the closure of many lotteries to stop servicemen stationed on the West Coast from spending their money on gambling; most did not re-open after the war.AG

Other banks (often termed “companies” on 20th-century tickets) I have seen include:The suffix of the ticket title in Chinese here indicates whether the ticket was for a day (日) or night (夜) draw. American Co. (Chinese title 花旗夜廠), Liberty Co. (自由日廠), Sun Set Co. (順式日廠), Cleveland Co. (企李倫夜廠), New World Co. (新世界夜廠), and Oregon Co. (柯利近日廠). In the Penn Museum are bundles of 19th-century tickets from Lee Kee Co. (利記廠) and Tai Kee Co. (泰記厰). Californian companies included Fook Tai (泰福夜厰), The Sun (?), Lee Tai (利泰日厰), Boston (保市頓), and American Co. (花旗).

In Australia

Chinese lotteries are first discussed in Australian newspapers in the 1860s; pak-a-pu is clearly described in one article of 1863.AH The game seems to have first appeared in the goldfields of Victoria, and the aforementioned article describes three or four banks operating in Castlemaine.

Despite one newspaper’s recommendation to “take a ticket, see the drawing, and so spend a very entertaining half-hour in a Chinese lottery-office,”AI by 1864 lotteries were being raided by police and the proprietors charged.AJ

The first explicit mention of the game that I have found under the name “pak-a-pu” is in 1873, when a case was brought against the proprietors of the Heng Hi store on Little Bourke Street in Melbourne for running a pak-a-pu bank.AK The bank was known as the “No. 6” or “You Lee” lottery. Picking all ten numbers on a sixpenny ticket would return £75. A similar case was brought against the “No. 2” or “Shing Lee” lottery in 1874.AL Both banks were reported to carry a capital of £300, which is also reported elsewhere as the standard amount carried (and usually limited the maximum payouts).

There were perhaps attempts by the banks to make themselves publicly acceptable, as in 1874 the “Chinese Pak-Cup-Pew Trading Company” made a donation of £100 towards the hospital in Melbourne.AM

In any case, despite suppression, the game became very popular in Melbourne: in 1876 it was reported that there were 25 agents operating in the area between Swanston and Russell streets.U (p. 7)

By 1877 the inequality between the prosecution of Chinese and European games was noted in the papers:

One of the most humiliating anomalies in our penal code is the law which visits fantan and pak-a-pu with fine and imprisonment, and winks complacently at the wholesale public gambling of Europeans. With the Chinese, games of chance are almost the sole national recreation in this colony, and it seems scarcely fair to enforce upon them the rigid and austere virtue which we take care never to practice ourselves. On the racecourse, in the stock exchange, and in the streets, betting goes on apace, and oftener than not the worldly prosperity of a man’s family hangs upon the issue of a wager.AN

However, not everyone agreed. The BulletinThe Bulletin was an astoundingly racist publication during this period, whose motto would soon be “Australia for the White Man”. claimed the opposite to be true:

If an Australian started a fan-tan hell, Darlinghursti.e. Darlinghurst > Gaol would be his home, and stone-breaking his employment, within a month; and indulgence in pak-ah-pu lottery would similarly mean penal seclusion for a lengthy period. But no such just retribution overtakes the Mongolian.AO

This article was accompanied by what has been called the “most scandalous and racist cartoon ever to grace the Australian media”,AP depicting “pak ah pu” as one leg of the “Mongolian octopus”, alongside “immorality”, “small-pox” and “typhoid”, “opium”, “fan tan”, “bribery”, “cheap labour”, and “customs robbery”.This cartoon was drawn by Phil May and is easy enough to find online.

In New Zealand

As in Australia, racist depictions of Chinese gambling were common. And yet, while newspaper reports often decried gambling and gamblers, others came to the defence of the game. Here I focus more heavily on the counter-current, as it is all too easy to find examples of the former.

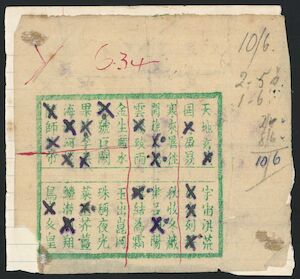

Legality and Hypocrisy

A used “pakapoo” ticket from New Zealand, probably from the 1920s. This ticket records four simultaneous bets on sets of five numbers; the drawn lines divide the ticket into four separate zones.

© Alexander Turnbull Library, used with permission: Eph-A-LOTTERY-1920s-01

Pakapoo was illegal from 1862 in Otago,Y (p. 93) and would be made illegal nationwide with the passage of the Gaming and Lotteries Act of 1881, where it was listed alongside Fan-Tan. The addition of the games was made despite the lawmakers’ lack of knowledge about what the games actually were:

Our representatives in Parliament seem to have had a good deal of fun over the Gaming and Lotteries Bill on Friday night. […] considerable amusement was caused by the numerous enquiries of Colonial Secretary Dick as to the meaning of the Chinese game of ‘fan-tan’. One after another of the members impressed upon him the necessity of giving full explanations, as no doubt he knew all about it, and badgered him on all sides. Amidst considerable cheering he shortly rose, and with signs of conscious ignorance, yet inward satisfaction, protested that he really did not know anything about it. Then numerous questions were asked as to who did know, and other members rose, and each gave delightfully varied descriptions, each member beseeching the Committee not to let words pass of which they did not know the meaning, as they might play ‘fan-tan’ without knowing it, which, in the light of subsequent and apparently authoritative explanation, seemed quite possible, seeing that it is simply termed ‘odd or even.’ Mr Barron increased the dilemma by moving that ‘pakapoo’ be inserted after ‘fan-tan’. The Colonial Secretary intimated that he did not know its meaning, but thought it a good word, and after the mover had satisfactorily explained that his knowledge was as exhaustive of ‘pakapoo’ as that of the Colonial Secretary of fan-tan, the words were added.AQ

By 1902 and 1903 there was some legal tussle over the status of the game due to unclear definitions in the Act.

Firstly, a case in 1902 concerning one “Joe Quick” (who had been fined several times for the game previously) reached the Supreme Court, and had its conviction quashed upon insufficient evidence.ARAS

At the time, Wellington’s Evening Post opined that:

… it seems the essence of petty spite to start a crusade against the cottager’s Christmas goose or the Chinaman’s pakapoo.AT

John Liddell Kelly’s bitingly sarcastic poem “In China” (1901) contains the following verse upon the topic:AU (p. 56)

The practice of gambling’s a terrible vice

’Mong the sin-sodden people of China!

Fan-tan, pak-a-pu, and a species of dice

Are all known to the gamblers of China.

True, we bet in our streets, and play cards in our pubs;

We have poker and nap in our big, toney clubs;

But we cannot attend to our own dirty dubs

While we’re preaching reform—out in China.

The decision of this case, wherein the Chief Justice mentioned — obiter dictum — that pakapoo was defined by the Act as a “game of chance” and not a lottery,AV was to have a lasting effect on other cases. In 1903 a case in the Magistrate’s Court was dismissed on the basis that pakapoo was a game of chance, and not a lottery;AW taken at face value, the Act stated that games of chance were only illegal if played in public places.

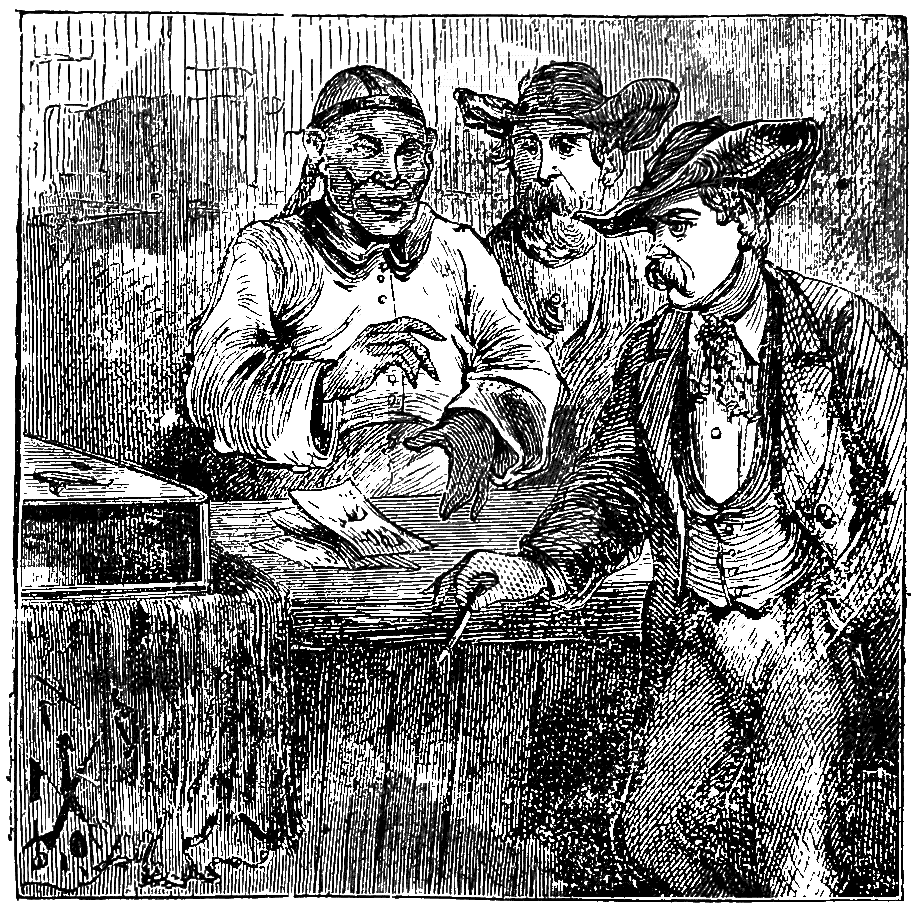

Two men in the “Southern Bank” on Walker Street in Dunedin, 1904.

© Alexander Turnbull Library, used with permission: PUBL-0090-001

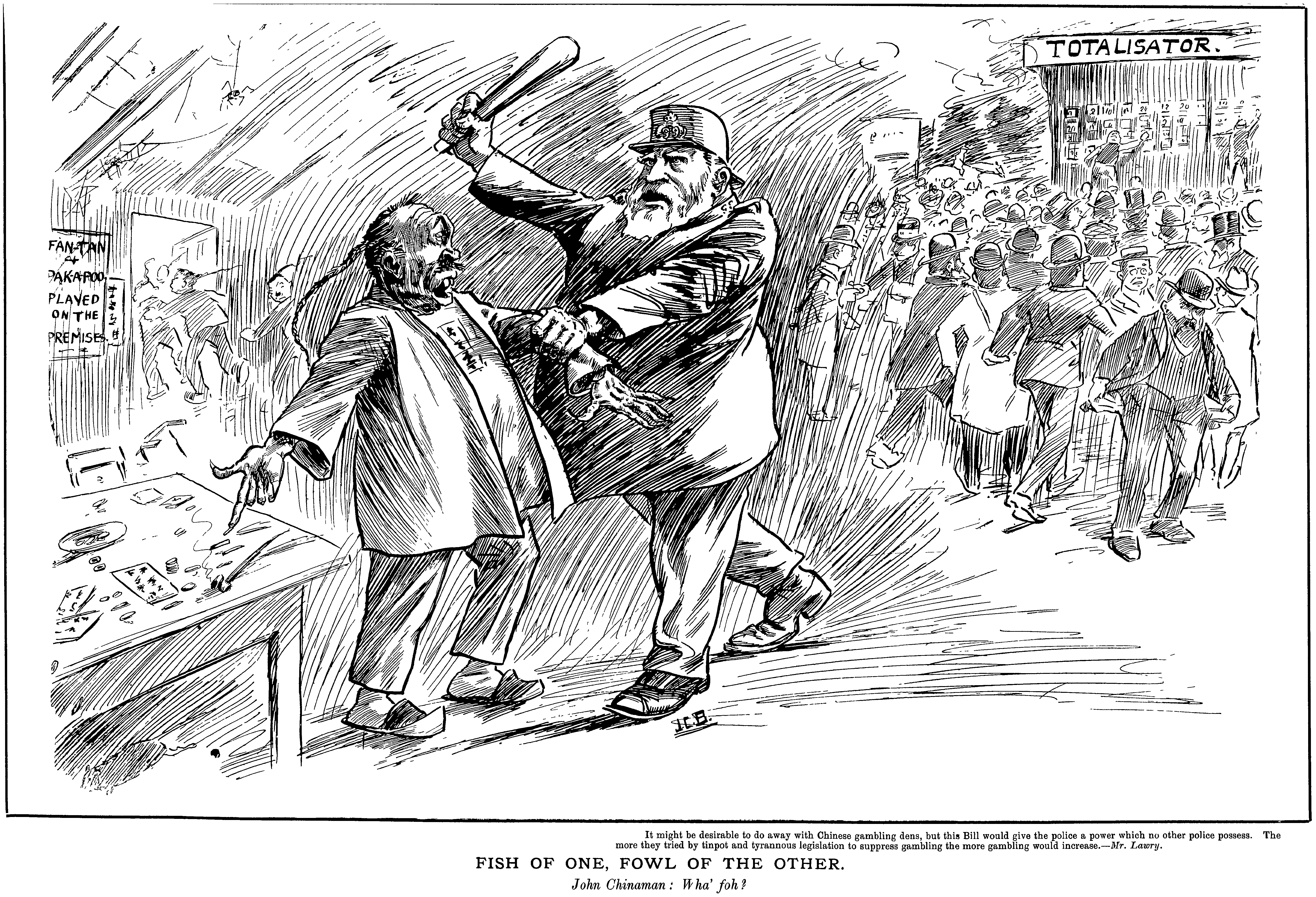

With the game seeming to be on the verge of becoming legal, in 1904, the “Gaming and Lotteries Act Amendment Bill” was introduced to parliament by James McGowan. The bill sought — among other things — to declare pakapoo a lottery, and thus ban it outright. By the reception of this bill in the newspapers, it is clear that this was felt to be inconsistent with laws governing games played by Europeans:

For a country which not only countenances the totalisator, but also derives revenue from it, it is the height of inconsistency to discriminate between different forms of gambling. Why should fan-tan be more wicked than bridge, or pakapoo than poker, and why should not both be legalised if it is legal to gamble by means of the totalisator?AX

During parliamentary debate on the proposed bill,

Mr Hone Hekei.e. Hōne Heke Ngāpua, a Liberal party member and great-nephew of the more famous Hōne Heke Pōkai. wanted to know why the Chinese were to be limited in their games and recreations, when lotteries at church bazaars were allowed to proceed without interference.

Mr W. FraserWilliam Fraser, at this point an independent, later a member of the conservative Reform party. thought it was right to punish Europeans found in a Chinese gambling house, but seeing that Europeans were allowed to participate in various games of chance, he objected to punishing Chinese for doing the same thing.AY

As noted in that last paragraph, it was often considered that the game was suitable for Chinese people but not Europeans. Robin Hyde, writing later in 1934, noted:

… the Chinese quarter in most cities suffers from its hangers-on. Auckland’s pakapoo dens receive such loving care from the police for much the same reason. No harm in a friendly all-Chinese game of fantan and pakapoo — and ninety-nine games out of a hundred are ‘on the level’ — but the drawing of the tickets induces whites of the very worst class to make the site thereof their little home away from home.Z (p. 235)

At one point it was even suggested by a police inspector that only Europeans should be fined for playing pakapoo, and that “it would be as hard to stop such recreation amongst the Chinese as to stop whist and other games amongst Europeans.”AZ

In any case, McGowan’s 1904 bill was subsequently withdrawn and this version of the amendment was never passed.

By 1906 the appetite had increased for regulation of all forms of gambling.

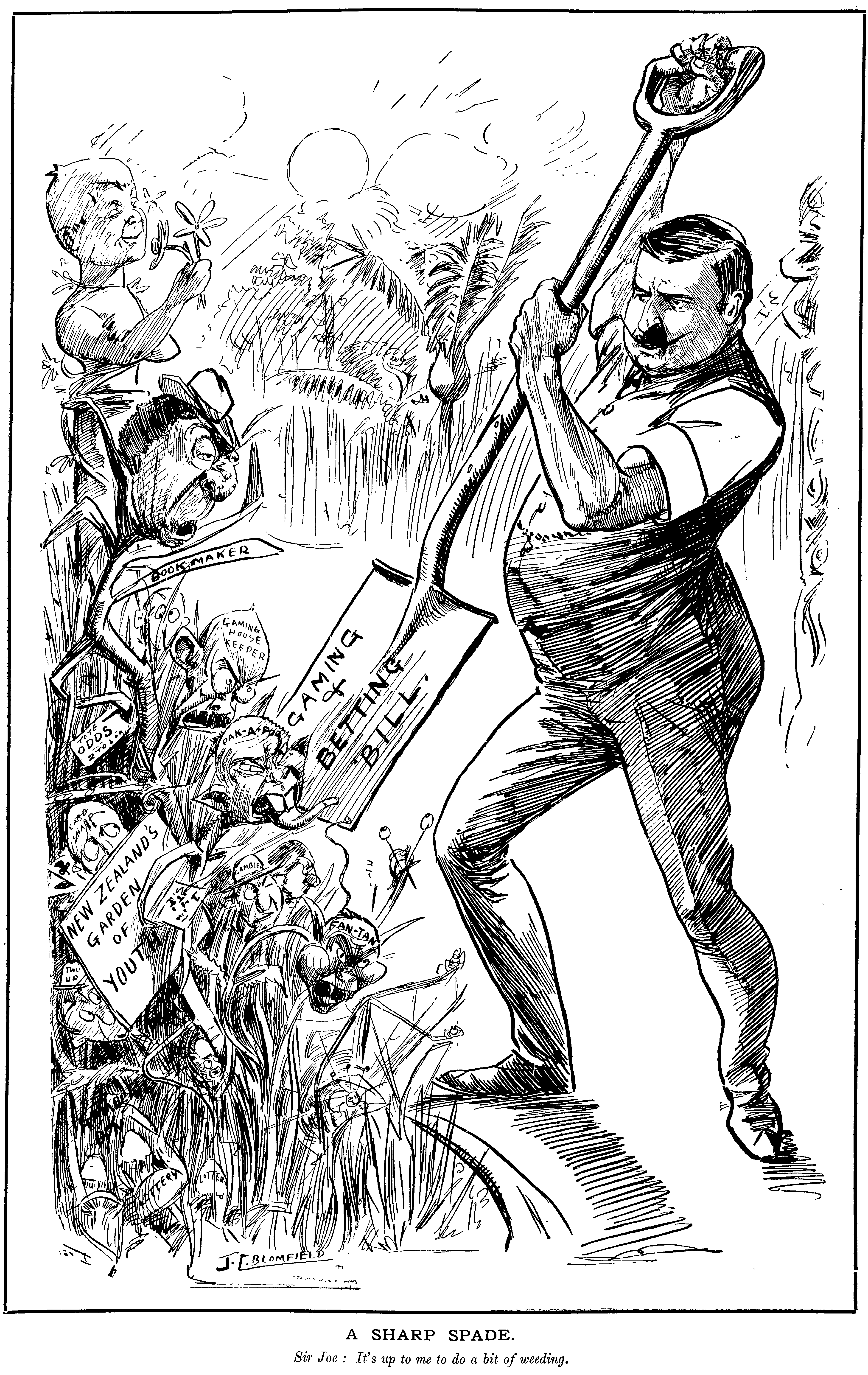

This 1904 cartoon from The Free Lance protests against the inconsistent application of gambling laws, whilst still portraying a Chinese man in a racist manner.

Only a year later, in 1905, the Supreme Court again heard a case regarding Pak-A-Poo (Lee Sun v. Daniel Conolly),BA and this time Justice Williams determined that not only was Pak-A-Poo a game of chance, but it was also a lottery, and therefore illegal.Apparently Williams and Stout were professional rivals — Williams had been passed over when Stout was selected as Chief Justice — and I am tempted to wonder if this had some part to play in the overruling of the earlier obiter dictum.

Finally, in 1907, the Gaming and Lotteries Act Amendment Act was passed, which declared all games of chance to be explicitly unlawful. The game was to remain illegal until the passage of a new Gaming and Lotteries Act in 1977.

Even after all gambling was made illegal, protests were made about the inequal application of the law, and these would continue throughout the twentieth century; in 1933, one businessman complained about the effect the ban could have upon trade with China:

“It is well known,” [Mr. John MacGibbon] said, “that in most homes in New Zealand the gambling laws are broken with impunity. This harrying of Chinese who play pakapoo and fan tan has an effect on Chinese who are likely to buy our products. It is well known that the Chinese are among the most law-abiding people in the world, and it should be remembered that we forced opium on them because of the profit in it. It is utter hypocrisy.” BB

Pakapoo tickets discovered during the demolition of a house on Wellington’s Haining Street, May 1960. Haining Street was the centre of Wellington’s Chinese community and had also been the centre of pakapoo activity: of the 53 buildings that existed on the street, 20 of them were used for pakapoo at some stage or another.BC (pp. 94–135)

© Alexander Turnbull Library, used with permission: PAColl-7796-35

Now that we are able to look back with the benefit of time and more sources, it is clear that, despite lurid newspaper and magazine reports of pakapoo dens and the supposed conditions thereof, the pakapoo shops functioned not only as a gambling house but as a meeting-place with a convivial atmosphere, providing a safe ‘third place’ for Chinese (men, at least) to gather, catch up on news from home, drink tea, and eat.M (p. 52, 62) Interviews with ex-police officers indicate that they thought it a “clean and well-run game”, and only raided the game when specific complaints had been made.M (p. 59)

During the remainder of the 20th century, pakapoo slowly dropped out of the public eye. I am not aware of any current use of the game — although it is now legal. Despite this disappearance, it was to have ongoing influence upon New Zealand: Allan Highet, who was responsible for early attempts to introduce Lotto as a government minister, had gained his appetite for gambling by purchasing pakapoo tickets in Haining Street during the 1930s.BD (p. 247)

In the United Kingdom

Pak-a-pu seems to have reached London later than the other locations discussed here; it doesn’t begin to appear in the newspaper until the early 1920s. Even as late as 1924 it is described as a “new gambling game”.BF

More evidence for this is that, although Fan-Tan is a feature of several stories in Thomas Burke’s 1917 collection Limehouse Nights — set in Limehouse, London’s main Chinese community at the time — Pak-a-pu is not, but it does make an appearance in his short story “The Yellow Box” which was first published in 1938.

In South Africa

According to The Bantu In The City (p. 219), four syndicates were operating throughout the Johannesburg area in 1935.

In Canada

Visiting in 1899, Liang Qichao stated that there were more than 15 pigeon lotteries operating in Vancouver.N (p. 191)

Globalization, or Kenoization

The “Chinese lottery” was to become Europeanized — and therefore, acceptable — through its adoption and development by American casino operators in the early 20th century. It is probable that there were many such attempts to adapt the game by both Chinese and Americans looking to popularize it,For example, Eugene Diullo, Harrah’s first keno manager, learned the game growing up in the mining town of Ely,BH (p. 125) but this was still at the time the Chinese game. but here I recount what appears to be the main thread of popularization which led to widespread commercial implementation of Keno.

Evidence of Chinese attempts at popularizing the game include tickets with numerals written in place of Chinese characters.

UC Berkeley, Ethnic Studies Library, 🅮: AAS ARC 2000/13: box: fol. 4

In the early 20th century, versions of the “Chinese lottery” were being played in Butte, Montana. Just like the examples above of other locations the game had spread to, Butte was a mining town with a significant migrant Chinese population. The game was played illegally in the backrooms of “cigar stores”, which also operated as speakeasies. One in particular, the Crown Cigar Store, was operating the Chinese game in 1927.BI (p. 50) A court case from 1948 shows that at the Crown the adapted game, using numbers, was at that time known as “the Crown Game” or the “Crown punchboard game”,AA but it was clearly derived from the “Chinese lottery”. The gambling operation was managed by two brothers named Joe and Francis Lyden.Some sources give the name as “Frances”. The Lyden brothers — Joseph Michael (1899–1982)BJ and Francis — were Irish immigrants who had inherited the store from their step-father.BK

These Butte games were routinely shut down by the police, but in 1931 Nevada legalized gambling by passing Assembly Bill No. 98 (popularly known as the “Wide Open Gambling Bill”). The bill explicitly legalized “keno”, as long as the person running the game had procured a license to do so. It is worth noting, given the ongoing theme of anti-Chinese discrimination here, that these licenses were only available to US citizens, and ‘aliens’ were not allowed to even operate a licensed game.This seems particularly egregious given that the distinctly Chinese game of Fan-Tan was also explicitly legalized by the bill… but only for US citizens!

At this time, the name “keno” (or “quino”) referred to a Bingo-like game from the 19th century (see the Keno (Bingo) article for more).Interestingly, one of the few books to get the distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new’ Keno straight is Playboy’s Illustrated Treasury of Gambling (p. 215). This game used pre-printed sheets and randomly-drawn numbers, and is not directly related to the Chinese-derived modern game of Keno, where sheets are marked by the players.

However, it seems that the Lyden brothers seized upon this opportunity to rebrand their game under the “keno” name. In 1935 Francis moved to Reno,Joe Lyden doesn’t feature any further in this story, but he would also later (after 1938?) move to Las Vegas and start the first Keno game there, at the Fremont. where he began to work for John Petricciani, owner of the newly-opened Palace Club.BM

“Chinese Keno”

As early as 1899, the Chinese game had been referred to as “Chinese Keno” to distinguish it from the existing Keno game.BN Despite this, earlier attempts to run the Chinese lottery under the “keno” name had failed: in 1932, one Woo Sing had purchased a Keno license under which to operate the “Chinese lottery” in the Henry ClubOne of the earliest licensed gambling establishments in Reno, located at 133 Lake Street. (located in Reno, Nevada), only to have the license revoked by the Reno city council and his staff arrested.BO While the case against the staff was eventually dropped, Woo Sing was unable to recover his $300 ($6870 in 2022 dollars) license fee. In May 1933, a J. B. Crane, an associate of Woo Sing’s, attempted to procure a license to run the game as “keno”.At the Lucky Club, 233 Lake Street. Crane stated (correctly) that the game was not actually a lottery and hence not illegal, and that his game would use numbers in place of Chinese characters, and the license was subsequently granted.BP By the middle of June the club had been ordered to stop the game,BQ then permitted to reopen it,BR until finally Crane’s licenses were revoked and his club was ordered shut.BSCrane had previously boasted that the council did not have the power to refuse a license, which must not have helped his cause.

Another operator named Walter Tun, who had watched the proceedings closely, also chose to close his “lottery” operation.BT While all this was going on there seems to have been something of a turf war between Tun and Sing,BU and in July, Woo Sing was shot by an unknown assailant.The case was never solved, despite a $500 ($11,400 in 2022) reward being offered for information by the Yick Keong Benevolent Association. Crane again sought licenses in July,BV and August,BW at which point the petition was referred to a grand jury in September,BX but I cannot find any further trace of it.Perhaps the death of Crane’s wife’s father in September brought an end to his pursuit of the matter.

A newspaper report of the time shows the confused reaction to Crane’s August application, as Crane’s lawyer James T. Boyd debated the meaning of “keno” with City Attorney Pike:BY

Pike—“Does the license ask for keno? Do they intend to play keno or Chinese keno?”

Boyd—“Try and find a definition for keno?”

Pike—“I can show you one in Corpus Juris and it does not include the Chinese game.”

Boyd—“Does it include the games played in places on Virginia street. Any time you take numbered balls out of—”

Pike—“They call the games on Virginia street tango—I don’t think they’re legal either.”Tango (from Spanish tengo, “I have it”) at this time also referred to a version of the Bingo-style Keno game.BZ It had been played since 1931 at the Reno Club on Virginia Street,CA and the name was probably influenced by the tango (dance) which was popular at the time.

By July 1934, things seem to have calmed down somewhat, as both Walter Tun and Woo Sing were simultaneously granted keno licenses, to operate at the Star Club and Public Club, respectively.CB Despite one councillor immediately attempting to revoke these licenses, and the debate reopening upon “Chinese keno”,CC they were apparently able to operate unmolested until May 1935, at which point the District Attorney stepped in and ordered them to shut down.CDWoo Sing would eventually be arrested on narcotics charges in 1937 and the Public Club closed down permanently.

Despite the repeated failure of these previous cases, Francis Lyden proposed running a “keno” game in Reno based upon the Chinese lottery, and contacted Warren Nelson, whom he knew from Butte, to run it at the Palace Club.CE (p. 26) At the time Warren was running games in Great Falls.

Warren had at first run the game in the backroom of the Mint Cigar Store in Butte.Warren states his father and a man named Cal Lewis ran the game together in the Mint Cigar Store, but that he was taught the game by a younger man named Jimmy Shea after his father refused to teach him.CF (p. 29) Initially, they had used the same method of drawing the numbers as in the Chinese version of the game (paper strips rolled and placed in four containers), but eventually moved on to using balls which were jumbled in a tumbler. The number of drawings was also increased to a much faster pace of one every fifteen minutes. It was this version of the game that was taken to the Palace Club in Nevada.CF (p. 34–5, 50–1)

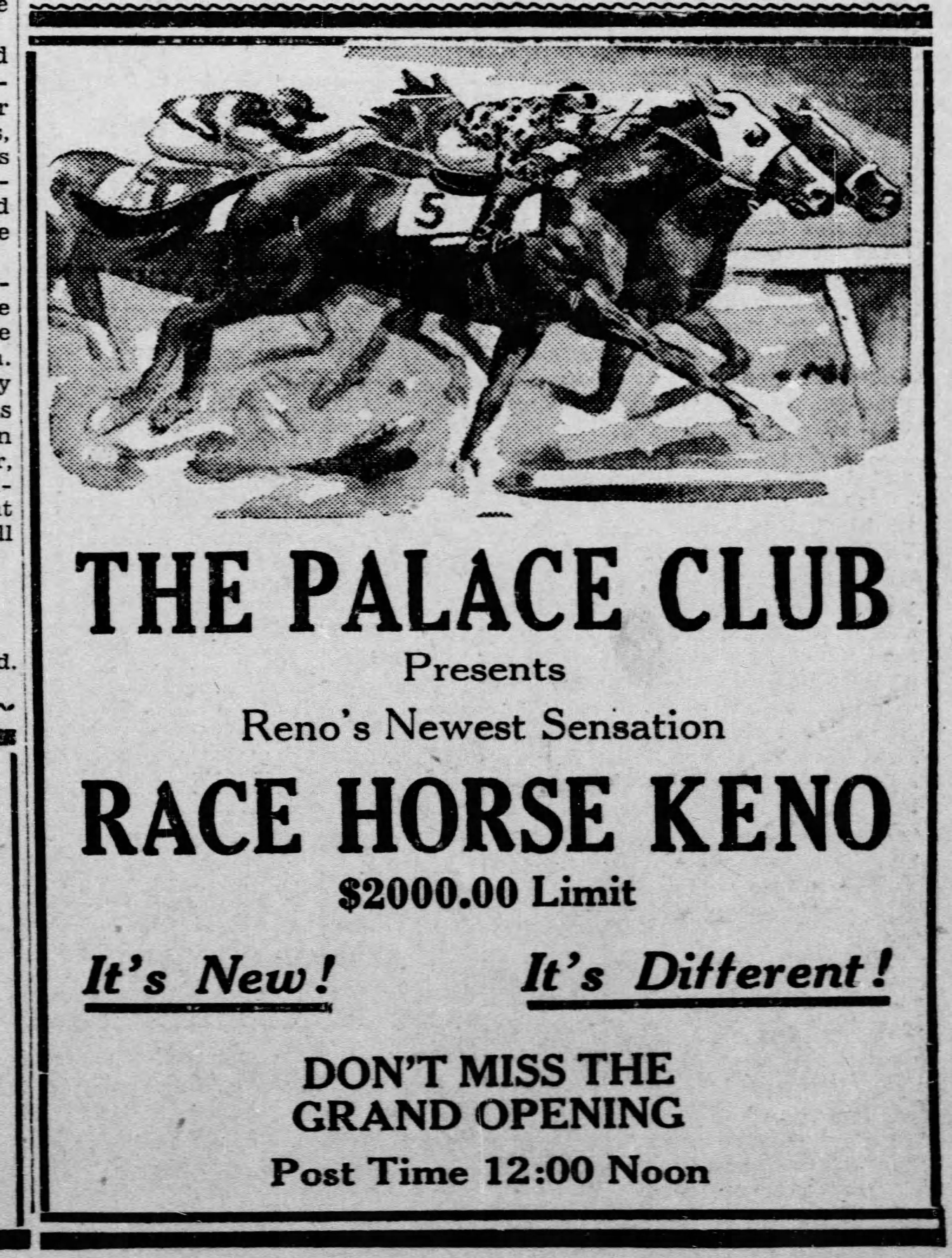

Thus, the first publicly played version of the Americanized game appears to have been “Race Horse Keno”, which was launched by the Palace Club in Reno in 1936. The game was given a horse-racing theme, and the Chinese characters were replaced by the numbers 1 to 80. Balls with these numbers could then be drawn to determine the “winning horses”. It is interesting to note that this inadvertently returned the game to its pigeon-racing roots.

Racehorse Keno

Race Horse Keno was introduced to the Palace Club in Reno upon its grand (re)opening on the 25th of April 1936.

As a game of chance and not a lottery, the “new” game was legal under Nevada laws.CE (p. 26) Warren describes in his own words how the game was lifted from the Chinese:CF (p. 30)

Keno, which was originally a Chinese game, was well known throughout the West. Everywhere you’d go, Chinese could be found running illegal keno games. Some of them had tried to start games in Butte, but their competition, white professional gamblers, would get their games closed up. Then a fellow went in partners with a Chinaman, and when he learned everything he could from him, he kicked him out. The Chinese were looked down upon so much that you could do anything to them and no one would say a word.

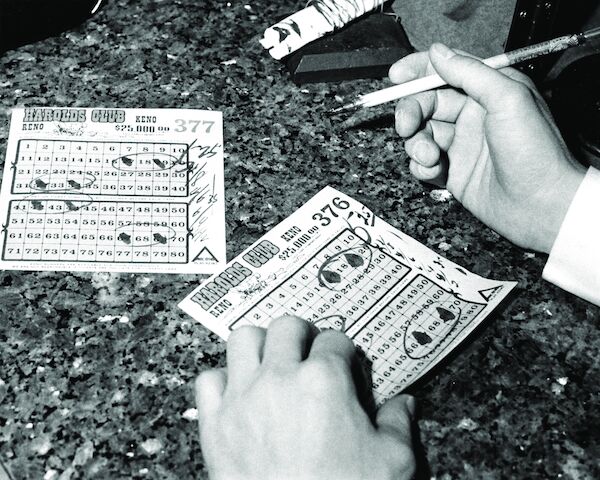

Despite purposefully divorcing the game from its Chinese origins, the keno “writers” who marked the tickets still used hair brushes imported from China,BH (p. 129) and the ink was purchased from Chinese suppliers.CF (p. 50)

A keno writer using a horsehair brush to mark tickets in Harolds Club, Nevada.

In this “racehorse” version of the game, each number had a horse’s name assigned to it, and the names were announced in a similar way to the way that “bingo calls” are now performed. Warren gives an example of the patter (or “ballyhoo”) that was used to announce the game, mimicking the style of a horse racing commentator:CF (p. 158)

All right, they’re off and running!

Jockey number 1 on Nanny Dee.

Jockey 16 on Mainstreet,

Right down the main drag.

You’ve got a hell of a race,

And a hell of a bunch of horses!

Jockey number 69 on Kay Dugan,

That old Irish girl again.

Other examples of horse names include:

The race-horse keno counter at Harolds Club in the 1940s. Note the “squirrel cage” containing the balls. The payoffs listed are identical to those reported at the Crown Cigar Store in Montana, 1948.AA

The Bank Club (the next-door rival of the Palace Club) and Harolds Club were soon to follow by installing Keno games of their own.CF (p. 53) In 1938 Warren opened the game at the Nevada Club in Lake Tahoe.CH (p. 10)

The racehorse version of the game died out some time in the mid 1950s.BH (p. 128) However, keno games are still referred to as races.CI (p. 23)

Keno

Modern Keno is much the same game as the Chinese lottery: the players select their numbers, the numbers are drawn and displayed — nowadays on an electronic ‘flashboard’ — and any winning bets are paid out.

Catches, Spots, & Ways

In modern parlance the traditional ticket would be called a 10-spot ticket, as ten numbers were chosen. Many casinos or other operators allow players to choose 1-spot to 10- or 15-spot tickets, or even higher — some offer 20-spot tickets.

The payoff tables vary depending on the number of spots chosen and are usually arranged by the number of catches: that is, numbers chosen that match the drawn numbers.

The basic ticket with a certain number of spots chosen is now called a straight ticket. Other ways of marking tickets indicate multiple simultaneous bets being placed. These bets could be placed as separate bets, but it is more convenient to mark them on one ticket.

The simplest form of this is a split ticket, which has a line (or multiple lines) drawn across it to separate two or more distinct bets on one ticket.

A way ticket has multiple circled groups of numbers written on it.Some writers distinguish between way tickets and ‘combination’ tickets, where a way ticket has all groups of the same size. However, this seems to be an unnecessary distinction. The player must then condition the ticket by indicating what their intended bets are. For example, if a ticket has three circled groups of four, this can be used as a 3-way 8-spot ticket (there are three ways of forming eight spots by combining the groups) by writing “3/8” and the amount bet on each way on the ticket. The total cost of the ticket is the amount bet per way multiplied by the number of ways. The same could also be used as a 3-way 4-spot ticket (by writing 3/4), and/or also a one-way 12-spot ticket (1/12), if the player wanted. On a way ticket an individual circled number is called a king, as it greatly increases the number of possible bets.

Extreme versions of the way-ticket include the 190-way 8-spot ticket, where all 80 numbers on the ticket are marked by dividing them into twenty groups.CI (p. 119) At a rate of 10¢/way, this costs $19 per race!

Casinos provide ‘keno books’ which indicate various ways to mark way tickets and the corresponding payoffs depending on what catches are made.Examples can be found here for Bally’s Las Vegas or the Sahara Las Vegas. See Complete Guide to Winning Keno for more examples. In some cases certain payoffs are “enhanced” and pay more than they would on a straight ticket.CI (p. 128) It has also happened that paybooks have contained mistakes, which has allowed players to capitalize on better odds for themselves.CI (p. 189)

Alternative bets

Other ways of placing bets change how the game works: a catch-all ticket only pays if all of your selected numbers match. Conversely, a catch-zero only pays if no numbers are matched. An all-or-nothing ticket combines both of these and wins if either all or none of the numbers match.

A top or bottom or left or right ticket is placed by dividing the ticket in half horizontally (or vertically, depending on the bet to be placed) and then writing T/B/L/R on the appropriate section to indicate which half of the ticket has been chosen. No spots are picked for this bet, and it wins if more numbers are drawn on the chosen half than the non-chosen half, paying more if more numbers end up there.CI (p. 90)

A top-or-bottom or left-or-right (also called top-and-bottom or left-and-right) bet is placed by marking both sides of the divided ticket. This bet wins if the distribution of numbers drawn is inequal, and wins more the more inequal the distribution is (usually requiring at least 13 on one side to pay out).CI (p. 91)

Other Keno games

There are many other Keno variants which are invented on a month-by-month basis by casinos. Wizard of Odds has an extensive list on their Keno page.

Outside the casino: “Lottery” Keno

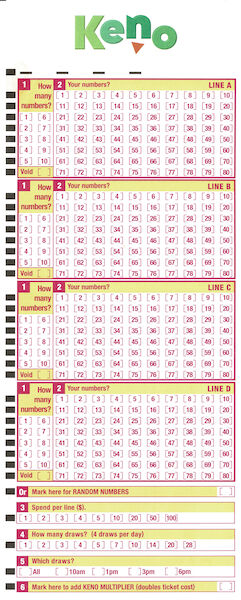

A modern non-casino Keno ticket, as used in New Zealand.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Keno is also run as a large-scale operation by lotteries operators. In this form of the game, only ‘straight’ tickets may be played — due to the number of different ways a ticket may be marked, the job of the ticket writers is highly skilled and not easily constrained to a computerizable form.

References

Dobree, C. T. (). Gambling Games of Malaya. The Caxton Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Culin, Stewart (). The Gambling Games of the Chinese in America. University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Hughes, Joan (ed.) (). Australian Words and Their Origins. Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. ISBN: 0-19-553087-X.

譚, 世寶 [Tán Shìbǎo] (). ‘“麻雀牌”與“白鴿票”之原詞形音義探討’ [text in Chinese]. Revista de Cultura vol. 93: pages 26–37.

Phillips, Ray E. (). The Bantu In The City. Lovedale Press: Lovedale, South Africa. First published in 1938.

Anonymous (). ‘“Pak-A-Peu” at Lawrence’. The Evening Star (6,899), : page 3. Dunedin, New Zealand.

Amor, M. Antunes (). ‘Macau: A Cidade Mais Pitoresca Do Nosso Dominio Ultramarino’ [text in Portuguese]. Ilustração Portuguesa (896), : pages 495–497.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Games of Chance’. The New York Times vol. 37 (11,360), : page 3.

Foo, Wong Chin (). ‘What the Heathen Plays: The Inner-Life of a Chinese Gambling Den’. Lowell Daily Courier, : page 2. Lowell, Mass., USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Police Court’. The Honoulu Advertiser, : page 2. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi.

Kling, Dwayne and Robert Thomas King (). A Family Affair: Harolds Club and the Smiths Remembered. University of Nevada Oral History Program: Reno, Nevada, USA. ISBN: 1-56475-388-3.

Lobscheid, William (). Grammar of the Chinese Language volume 2. Hong Kong.

Shum, Lynette (). Representing Haining Street: Wellington’s Chinatown 1920–1960 volume 1. Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington, New Zealand.

Li, En (). Betting on Empire: A Socio-Cultural History of Gambling in Late-Qing China. PhD thesis, Washington University: St. Louis, MO, USA.

趙, 爾巽 [Zhào Ěrxùn] (). ‘列傳一百四十一’ [text in Chinese]. In 清史稿.

Godinho, Jorge (). ‘A History of Games of Chance in Macau: Part 2 — The Foundation of the Macau Gaming Industry’. Gaming Law Review and Economics vol. 17 (2): pages 107–117. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2263191.

Nong, Sunny Zhenzhen, Lawrence Hoc Nang Fong, Davis Ka Chio Fong, and Desmond Lam (). ‘Segmenting Chinese Gamblers Based on Gambling Forms: A Latent Class Analysis’. Journal of Gambling Studies vol. 36: pages 141–159. doi:10.1007/s10899-019-09877-6.

何, 漢威 [Ho Hon-wai] (). ‘清末廣東的賭博與賭稅’ [Gamble and Gambling Taxes in Late Ch’ing Kwangtung; text in Chinese] [archived]. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica vol. 66 (2), .

Ho, Hon-wai [何漢威] (). Gambling Operations in Late Qing Guangdong [archived]; The Asian Business History Occasional Paper Series number 2. Asian Business History Centre – History Department, The University of Queensland. ISBN: 1-86499-044-9.

Mechigian, John (). Encyclopedia of Keno. Funtime Enterprises: Fresno, California.

Anonymous (). ‘In A Chinese Lottery Shop’. Australasian Sketcher vol. 4 (40), : page 6. Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Gambling in Sydney’. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser vol. 43 (5,913), : page 7. New South Wales, Australia.

Calvert, Samuel (). ‘Chinese Lotteries—Drawing the Numbers for the Bank Ticket’ [archived]. On the website State Library Victoria (accessed ).

Anonymous (). ‘Sydney Fan-Taneries and Lottery Cribs’. The Bulletin vol. 3 (134), : page 22.

Shum, Lynette (). ‘Remembering Chinatown: Haining Street of Wellington’. Pages 73–93 in Unfolding History, Evolving Identity: The Chinese in New Zealand, edited by Manying Ip. Auckland University Press: Auckland, New Zealand. ISBN: 1-86940-289-8.

Boddy, Gillian and Jacqueline Matthews (eds.) (). Disputed Ground: Robin Hyde, Journalist. Victoria University Press: Wellington, New Zealand. ISBN: 0-86473-204-X.

Supreme Court of Montana (). ‘State v. Crown Cigar Store’. Supreme Court of Montana.

Twain, Mark (). Roughing It. American Publishing Company: Hartford, Connecticut.

Quinn, John Philip (). Fools of Fortune, or, Gambling and Gamblers. G. L. Howe & Co.: Chicago, IL, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Fan-Tan Games to Reopen’. The New York Times, : page 9. New York, NY, USA.

San Francisco Board of Supervisors (). San Francisco Municipal Reports for the Fiscal Year 1892–93, Ending June 30, 1893 volume 1. San Francisco Board of Supervisors: San Francisco.

San Francisco Board of Supervisors (). San Francisco Municipal Reports for the Fiscal Year 1897–98, Ending June 30, 1898 volume 1. San Francisco Board of Supervisors: San Francisco.

Chin, Donnie (). ‘When Chinatown had its own lotteries’. International Examiner vol. 10 (1), : page 5. Seattle, WA, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘The Chinese Lottery’. Mount Alexander Mail (1,390), : page 3. Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Saturday, May 28, 1864’. The Argus (5,608), : page 5. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Police Courts: City Court: A Chinese Lottery’. The Herald vol. 75 (5,841), : page 3. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘The Chinese Gambling Houses’. The Age (5,665), : page 3. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘The Chinese Lottery Cases’. The Age (6,092), : page 4. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Melbourne’. Geelong Advertiser (8,398), : page 3. Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Editorial’. The Gippsland Times (1,976), : page 2. Gippsland, Victoria, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘The Chinese in Australia: Their Vices and Their Victims’. The Bulletin vol. 4 (171), : page 11.

Anonymous (). ‘Racism rife aboard the Shanghai Trader’. The Canberra Times vol. 60 (18,592), : page 17. Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Anonymous (). ‘Political’. Clutha Leader vol. 8 (408), : page 3. Balcutha, Otago, New Zealand.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Gaming Cases: Appeal to the Supreme Court — When Does A Man Play Pak-A-Pu?’. New Zealand Times vol. 72 (4,632), : page 7.

Anonymous (). ‘Supreme Court: Sitting in Banco — Important Judgement’. New Zealand Times vol. 72 (4,634), : page 2.

Anonymous (). ‘The Policeman and the Geese’. Evening Post vol. 63 (11), : page 4.

Kelly, John Liddell (). Heather and Fern: songs of Scotland and Maoriland. New Zealand Times Company: Wellington, New Zealand.

Stout, C. J. (). ‘Joe Quick (and others) v. Cox’. New Zealand Gazette Law Reports vol. 7: pages 492–494.

Anonymous (). ‘Pak-A-Poo Is Not A Lottery: The Chief Justice’s Recent Dictum — Followed By The Magistrate’. Evening Star (11,946), : page 4.

Anonymous (). ‘Daily Notes: Inconsistent Legislation’. Star (8,072), : page 2.

Anonymous (). ‘Parliamentary: House of Representatives’. Oamaru Mail vol. 29 (8,568), : page 4.

Anonymous (). ‘Political Gossip: Gambling Among Chinese’. The Evening Star (12,279), : page 7.

Williams, J. (). ‘Lee Sun v. Daniel Conolly’. New Zealand Gazette Law Reports vol. 7: pages 494–497.

Anonymous (). ‘Harrying of Chinese’. Evening Post vol. 116 (60), : page 9.

Shum, Lynette (). Representing Haining Street: Wellington’s Chinatown 1920–1960 volume 2. Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington, New Zealand.

Grant, David (). On A Roll: A History of Gambling & Lotteries in New Zealand. Victoria University Press: Wellington, New Zealand. ISBN: 0-86473-266-X.

Dearling, Robert, Celia Dearling, and Brian Rust (). The Guinness Book of Music Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives: Middlesex, England, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘New Gambling Game’. Derby Daily Telegraph vol. 74 (13,756), : page 3. Derby, England, UK.

Burke, Thomas (). Limehouse Nights. Robert M. McBride & Company: New York, NY, USA.

Kling, Dwayne (). Every Light Was On: Bill Harrah and His Clubs Remembered, edited by Robert Thomas King. University of Nevada Oral History Program: Reno, Nevada, USA.

Gibson, Richard I. (). Lost Butte, Montana. The History Press: Charleston, SC, USA. ISBN: 978-1-61423-819-5.

Associated Press (). ‘Joseph Michael Lyden’. The New York Times, : pages 6 (Section B). New York, NY, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Peter Naughton Passes on Coast’. Montana Standard: Butte vol. 75 (178), : page 2. Butte, Montana, USA.

Carroll, David (). Playboy’s Illustrated Treasury of Gambling. Crown Publishers: New York. ISBN: 0-517-53050-3.

Anonymous (). ‘Reno After Dark’. Nevada State Journal vol. 65 (205), : page 9. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Gamblers Raided By Police’. Washington Times (1,871), : page 8. Washington, District of Columbia, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Lottery And Keno Contrasted At Trial Of Chinese’. Reno Evening Gazette (234), : page 10. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Crane Is Issued Keno License By Council’. Reno Evening Gazette (123), : page 16. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Lottery Ordered Closed By Official Of City’. Reno Evening Gazette (136), : page 12. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese “Keno” Games To Operate’. Reno Evening Gazette (140), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Mayor Decides Who’s Who’. Nevada State Journal vol. 62 (322), : page 1. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Council Revokes Crane’s Game Permits’. Reno Evening Gazette (143), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Dispute Settlement Is Tried But Fails’. Reno Evening Gazette (206), : page 12. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Gambler Is Wounded By Gunman At His Home’. Reno Evening Gazette (172), : page 12. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Council Adjourns And Crane Fails In License Plea’. Nevada State Journal vol. 62 (282), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Washoe Co. Grand Jury Will Make Its Report Today’. Nevada State Journal vol. 62 (312), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘‘We Are Recessed,’ Says Mayor: And Recess Was Taken as His Honor Marched Out — Council Holds Hectic Session’. Reno Evening Gazette (194), : page 12. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘You Can’t Miss’. Nevada State Journal vol. 57 (257), : page 8. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Open Today: The Reno Club (Advertisement)’. Nevada State Journal vol. 57 (60), : page 8. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Granted Keno Licenses By Council’. Reno Evening Gazette (164), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Keno Discussion Again Heard By Council’. Reno Evening Gazette (176), : page 2. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Anonymous (). ‘Chinese Lotteries Ordered Closed by District Attorney’. Reno Evening Gazette (117), : page 14. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Totton, Kathryn M. (). Silvio E. Petricciani: The Evolution of Gaming in Nevada: The Twenties to the Eighties. University of Nevada Oral History Program: Reno, Nevada, USA.

Adams, Ken, Robert Thomas King, and Gail K. Nelson (). Always Bet on the Butcher: Warren Nelson and Casino Gaming, 1930s–1980s. University of Nevada Oral History Program: Reno, Nevada, USA.

Langford, Johnny (). ‘Center Street Gossip’. Nevada State Journal vol. 67 (102), : page 5. Reno, Nevada, USA.

Becker, Keith (). Warren Nelson: Gaming From the Old Days to Computers. University of Nevada Oral History Program: Reno, Nevada, USA.

Cowles, David W. (). Complete Guide to Winning Keno. Cardoza Publishing: New York. ISBN: 0-940685-62-0.