The History & Art of Hanafuda

Last updated: .

Hanafuda (“flower cards”) are striking. Their bright, colourful designs depict twelve months of flowers, birds, and natural scenes. Drifts of cherry blossoms fall across one card, the full moon glows on another, while a poet shelters beneath his umbrella in the rain. But where do they come from?

A search for antecedents takes us back centuries — before playing cards were even introduced to the islands of Japan — to the aristocratic “object-comparing” (物合わせ mono-awase) games of the Heian era (平安, 794–1185).

The cards themselves first appeared in the middle of the Edo period (江戸, 1603–1868). But the long path from courtly contests to mass-produced playing cards was neither direct nor inevitable.

Contested Origins

Picture two teams of Japanese courtiers dressed in opposing colours, competing in front of the rest of the court for prestige and influence — being judged not on their martial ability but for their æsthetic sensibility to curate and choose. Their goal was to present, with accompanying poem, the best representative of a selected category, which could be a food, flower, animal, or artefact. This was the game of mono-awase — a contest of æsthetic judgement which helped to define what it meant to be cultured, and which formed an integral part of aristocratic culture.The same terminology of awase was also used for sports such as cock-fighting.A (p. 165)

The idea was simple: players would bring a chosen item and argue for its superior qualities or unique attributes. Items that could be judged in these competitions ranged from craftworks such as fans or paintings,B (242) products including various types of incense or tea,C (26) through to natural specimens: flowers and plants (particularly chrysanthemums, iris roots,A (163) wild pinks), and animals both wild and domesticated (singing insects and songbirdsA (163)). But it is the category of shells which most interests us here, as it would — eventually — lead to Hanafuda.

These competitions were generally organized between two teams named Left (who initiated the game, and usually was the team with higher-ranking members)In Japan, the left-hand side was traditionally considered the dominant or “masculine” side (see the naming of shells below), the opposite of European tradition. In the Heian period, the Minister of the Left (左大臣) outranked the Minister of the Right (右大臣). and Right. The format was a series of rounds in which each team would present one item at a time, often with accompanying poem. Another style of game involved the presentation of a selection of objects on a miniature artificial garden or island called a suhama (洲浜), which was constructed especially for the competition and which could be made out of expensive wood or precious metals. The teams were outfitted in different colours — the Left in warm colours, orange or purple, the Right in cool, yellow or blue — and their accompaniments could also be chosen to match the team colours.D (90)

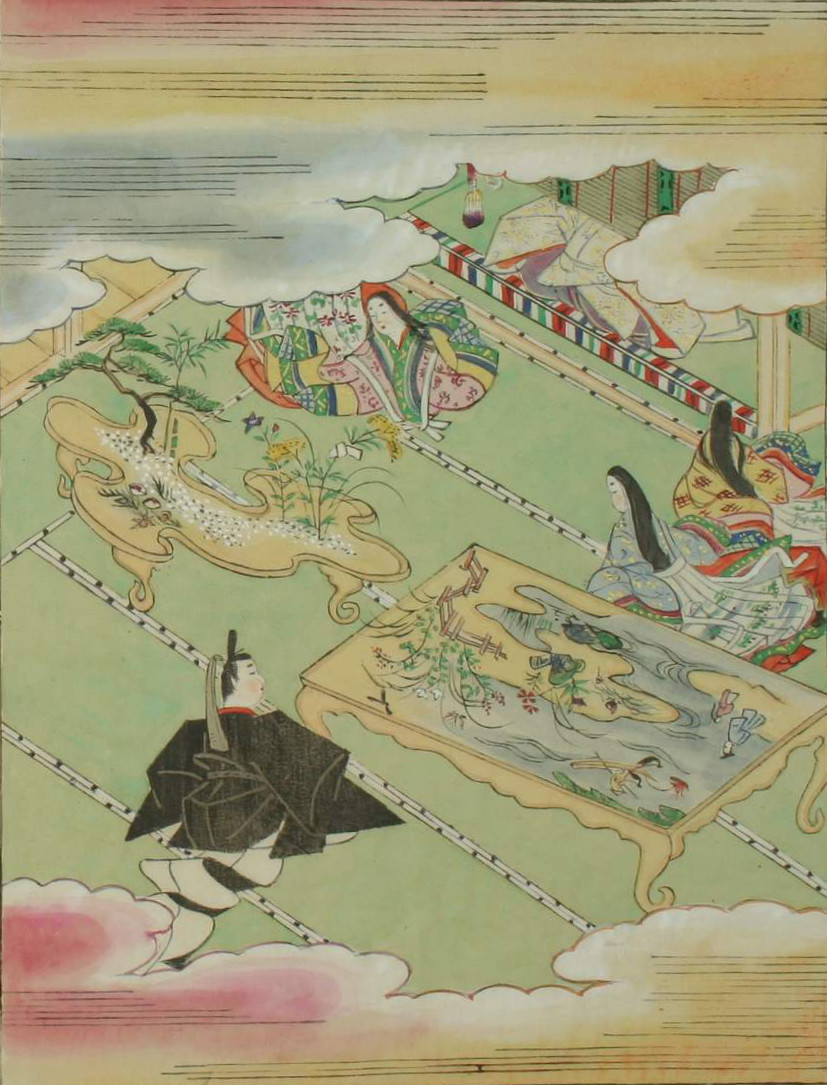

A depiction of the full-moon competition including two suhama, from an edition of unknown date.

On the night of the great autumn moon in 966 (which always fell on the 15th day of the 8th month in the lunisolar calendar), Emperor Murakami staged a lavish mono-awase contest. The construction of each team’s suhama is recorded in the Eiga Monogatari:

Both sides worked furiously, determined not to be outdone. The contestants from the Office of Painting submitted a painted landscape tray depicting flowering plants of heavenly beauty, a garden stream, and massive rocks. Various kinds of insects were lodged in a rustic fence made of silver foil. The artists had also painted a view of the Ōi River, showing figures strolling nearby and cormorant boats with basket fires. Near the insects there was a poem.

The Office of Palace Works presented an interesting tray, carved with great ingenuity to resemble a high tide, which they had planted with artificial flowers and carved bamboo and pines. Their poem was attached to a spray of fresh ominaeshi.E (p. 92)

These elaborate competitions could run all night. Another famous competition held by Emperor Murakami six years earlier — on the 30th day of the 3rd month of 960 — ran from 4 p.m. until it ended at sunrise with the winning team staggering out of the palace drunk, singing and dancing. A courtier’s diary records the elaborate preparations made for the participants:F (pp. 214–217)

[…] Special care was taken on this occasion as many eminent people of refined taste would be attending the event, and so new plants and flowers were carefully chosen and added to the garden. The Chamberlain Minor Captain Sukenobu was in charge of the garden, and he had oak logs arranged like a fence and entwined with ivy so that it looked like a cedar forest. He also placed stepping stones here and there so that one could walk along on them. The garden gave the impression of a pastoral landscape and looked more delightful than usual.

The blinds were replaced by new ones. The Emperor’s seat was arranged in the anteroom at the southern end of the gallery. The atmosphere was so pleasant that it defied description. […]

[…] The poems [of the Left] were engraved on the silver leaves of golden-yellow mountain roses placed in the suhama—truly a beautiful work of art of exquisite workmanship. The tables were made of rosewood and other wood. The design of the suhama was quite interesting and charming. The cover was of varied shades of dark red and wisteria were embroidered on it; the mat was of violet brocade. Then two court girls […] brought in another suhama for scoring, the design of which was wisteria tendrils made of gold and silver. A twig was to be removed each time a point was scored.

As mentioned in the last paragraph, a special suhama could be used for scoring. During a contest in 1035 one side planted miniature pine trees to track their score; at another in 1078, “the Left inserted arrows with silver shafts and glass feathers into a target to mark their wins, and the Right placed tiny replicas of musical instruments in a silver box inlaid with crystal.”B (p. 243)Elaborate scoring tracks were also used for incense competitions.

An aside about Uta-awase

Of all the types of competition, poetry matches (歌合わせ uta-awase) eventually became the most esteemed. At first they were competitions in the same manner as the others, where the poem was treated as an object to be chosen and presented by the competitor, where the poet might not even be present at the event, and more attention was paid to the accompanying costumes and music than the quality of the poetry.B (242)

The poetry competition was highly ritualized, where the result of a contest was not only about who could compose the better poem; on average, authors of a higher rank were more likely to win. In some cases, the winner of a round was decided by convention, and furthermore, some poems could not lose. The first poem presented by the Left team, a poem complimenting the host, or a poem by the Emperor himself would at worst result in a draw.G (102) At one competition Emperor Uda (宇多天皇) awarded his own poem a draw, stating “how can an imperial poem lose?”B (244)

Later, during what author Ito Setsuko terms the “silver age” of uta-awase,F (207) the work of the poet became more important, and poetry competitions were held without the extravagant suhama. The competitions became more austere and aware of the world outside the courtly realm; in 1083 a planned grand competition was cancelled as it was thought to be inappropriate given the unrest at the time.perhaps the Gosannen War. Smaller and more intimate competitions were held with poetry as their focus. This doesn’t mean that the proceedings were any less elaborate; the largest competition of this type involved nine poets competing over 1500 rounds.

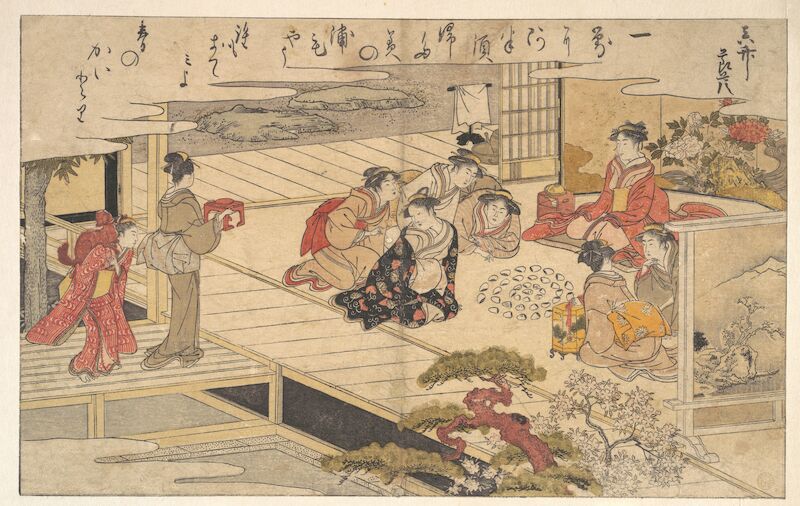

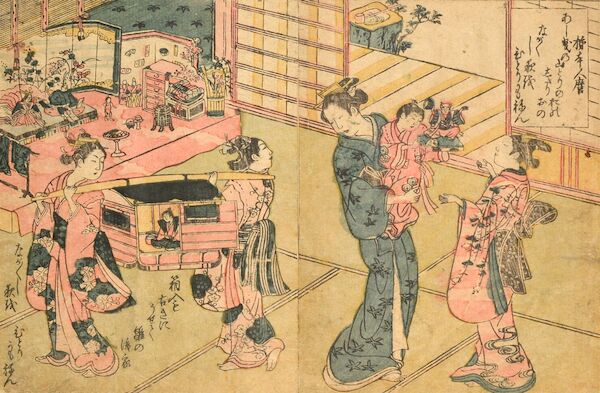

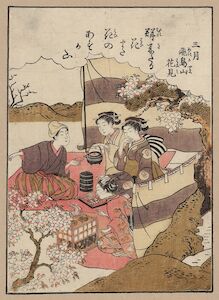

Ladies playing a game of kai-ōi.

From Gifts from the Ebb Tide 潮干のつと (1790), by Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿).

Kai-awase to Kai-ōi

While poetry competitions evolved toward greater pomp and complexity, another category of mono-awase was taking a different path.

The earliest recorded kai-awase (貝合せ, ‘shell competition’) contest dates from 1040, and was held at the Ise shrine by Emperor Go-Suzaku’s first daughter, Princess Nagako. This was a competition very much in the spirit of the other mono-awase games, and consisted of twenty rounds, each shell being presented with an accompanying poem.H (p. 269)

Kai-awase developed from this early comparing-competition form into a completely different style of game called kai-ōi (貝覆い, ‘shell covering’) that was based upon collecting matching pairs of shells. Kai-awase itself died out and there is no record of any competitions taking place after the Heian period.H (270) By the Edo period, these two terms would be conflated, with kai-awase being used for the matching game as well,IH (270) and today kai-awase is the term most commonly used for replica game sets.

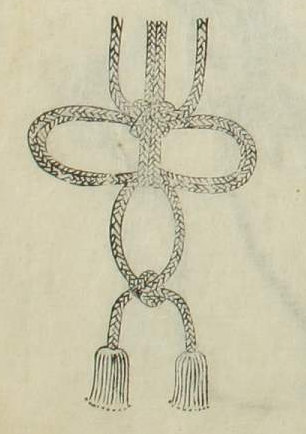

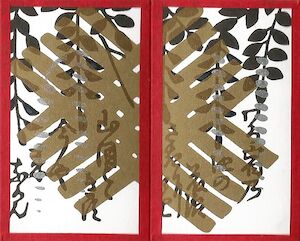

These diagrams indicate knots that could be tied on the decorative cord (組紐 kumihimo) which is used to secure the kai-oke. Two different knots are used to distinguish the “ground” shells (left) from the “coming out” shells (right). From Brocade of Shellfish 貝尽浦の錦 (1751) by Ōeda Ryūhō (大枝流芳).

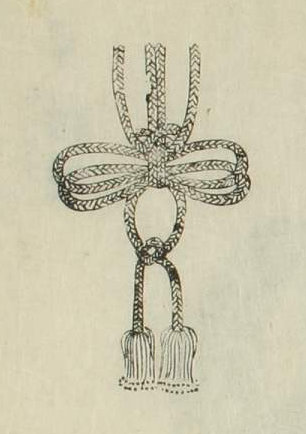

Four generations of women playing kai-ōi.

From 女有職莩文庫 (1866), by Okada Tamayama (岡田玉山).

Unlike kai-awase, the new game was exclusively played with clam (蛤) shells, and it offered definitive terms for deciding the winner. In one method of play, the left-hand sides of the shells — also termed the “male” (陽 yō = yang) or ‘ground’ (地) shells — were arranged face-down on the ground. The right-hand sides — the “female” (陰 in = yin) or ‘coming out’ (出) shells — were then drawn from their kai-oke (貝桶, ‘shell bucket’) one-by-one and the players would attempt to match them with those on the floor.D (92) Whoever was the first to point out a (successful) match would capture both halves of the shell, and the winner was the player who collected the most shells.

Early instructional books for women from the Muromachi period (1392–1573) include rules that state that the game is played with twelve shells,A video showing how this game would have been played can be seen here. which should be arranged in a circle on the ground, and that the drawn shell should be placed in the centre, with the pointed end (“head”) directed towards the highest-ranking person in the room.H (270) The game could apparently grow heated: those same manuals warned their readers that “to quarrel and remove shells by force is something that only men and courtesans do.”

The monk Kenkō (兼好, d. c. 1352) also offered guidance in his book Essays in Idleness, published around 1330:J (130)

If someone engaged in a game of shell matching neglects the shells in front of him while he looks around to check what others might be hiding in their sleeves or by their knees, his own shells will be snatched from in front of him. Those who are good at the game seem not to go to the length of taking shells from distant players but limit themselves to those close at hand, yet they manage to acquire a large number.

While later depictions (such as the images above) usually represent the game as only played by women, diary entries and paintings from the time show that the game was originally played by everyone, often in mixed teams. Losing teams would also request re-matches to try to beat the victorious team.H (257)

Records of the imperial household indicate that the shell-matching game was played formally nearly five hundred times over the period 1481–1589, sometimes as many as nine times a month.H (257)

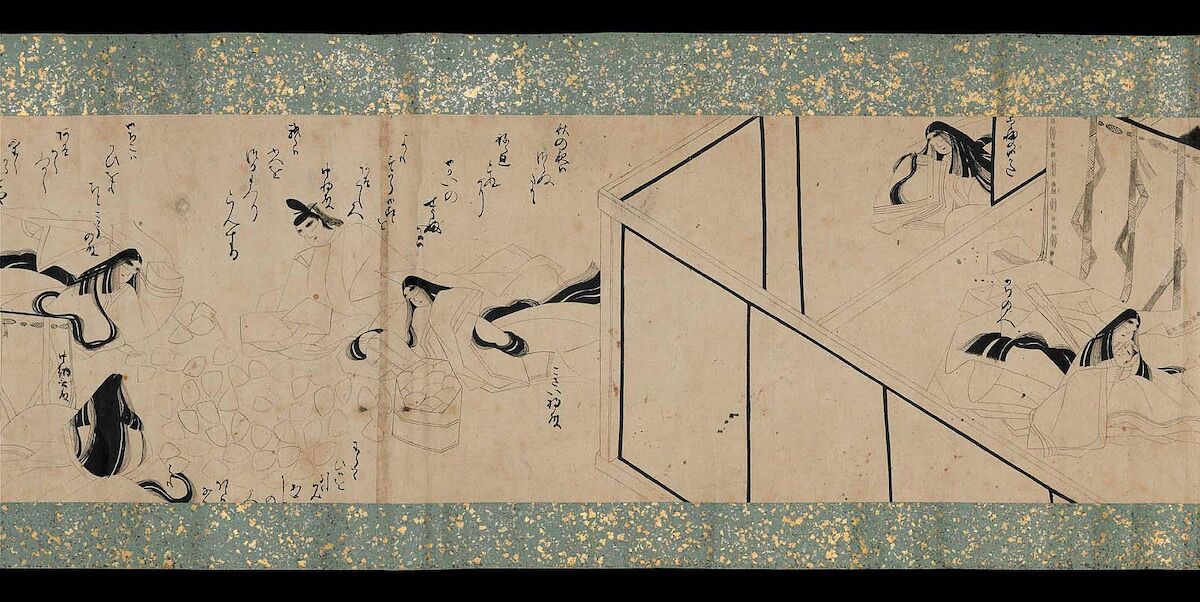

This early depiction from the 16th-century scroll Tale of Brief Slumbers うたたね草紙 shows a mixed group playing kai-ōi (at left).

When played with many shells, the game must have been difficult, since the clues that point to a match are solely the subtle shades and contours of the shell, and the only way to test if shells truly match is to pick them up and attempt to join them together. In fact, white shells with few markings were specifically selected to make the game as difficult as possible.K (11) Considering that traditional sets could contain up to 360 shells,Modern replicas usually only have around 54, but an elaborate set produced between 2013–2015 by forty-six artisans in Wajima contains 720 shells featuring Australian wild flowers.K (4) this was a game for a class of person who had a lot of leisure time on their hands.

Later the game set itself turned into a luxury item: the interior of the shells was at first decorated with matching fabrics, and then elaborately painted or even gilded. These matching images were used to confirm a correct match after both shells were selected. After the Kamakura period (1185–1333), it became common to illustrate the shells with matching scenes from the Tale of Genji (源氏物語 Genji Monogatari) — the game is also played in Chapter 45 of the novel itself. Other designs included shells with half of a poem in each, so that the matching pair could be read as a complete poem; these types of the game would eventually evolve into the uta-garuta (歌骨牌) poetry cards.

An 18th-century kai-ōi set. The paired boxes are the kai-oke, and half of each shell pair was stored in each bucket. The shells are decorated with painted scenes.

By the 17th century, a personal kai-ōi set became a standard component of a noble bride’s wedding gifts. The sets carried symbolic weight as the joining of the matching shells echoed the joining of husband and wife in marriage. However, the elaborate sets with their hand-painted and gilded interiors must have been expensive to create and only owned by the richest of families. Indeed, at times restrictions were put in place so that only noble families of the upper ranks were permitted to include the game in their bridal trousseaux.H (265) When the time came to hand over the wedding gifts, it was customary for the kai-oke to be the first item presented,H (265) and they were eventually to become the most important of all the gifts given to the bride.K (11) This custom faded away as samurai culture declined and was eventually abolished in the late 19th century.K (11)

In this role, miniature kai-oke can be found in hina-matsuri collections, and these are still produced for this purpose today.

Detail of the miniature kai-oke in the print.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

A miniature kai-oke can be seen in this depiction of a hina-matsuri set.

By Okumura Masanobu (奥村政信, 1686–1764).

Hana-awase

The painted shells with their matching pairs, the poetry, and the seasonal themes would all be recombined in a new form with the introduction of (Portuguese) playing cards to Japan in the mid 16th century.

Hanafuda seem to originate in a combination of the themes of kai-awase — matching sets, poetry, conventionalized art — with the ideas introduced by the Portuguese playing cards — a regular structure of suits divided into different ranks.

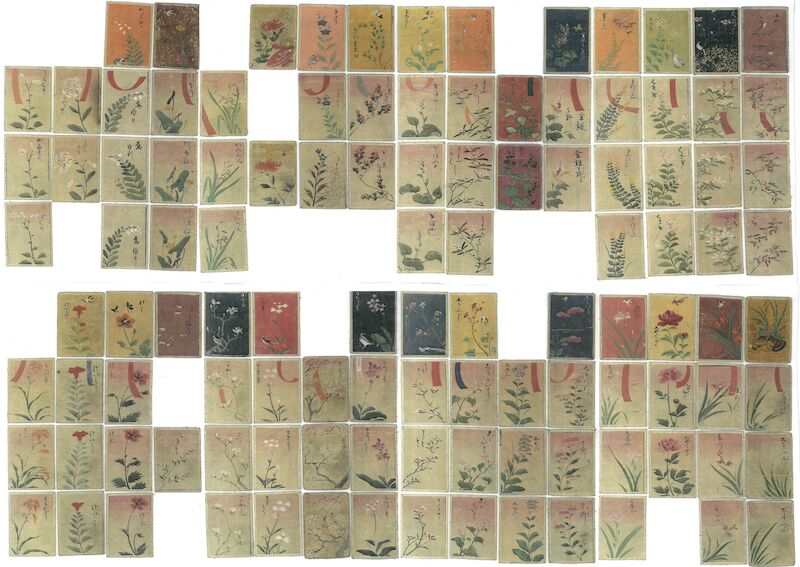

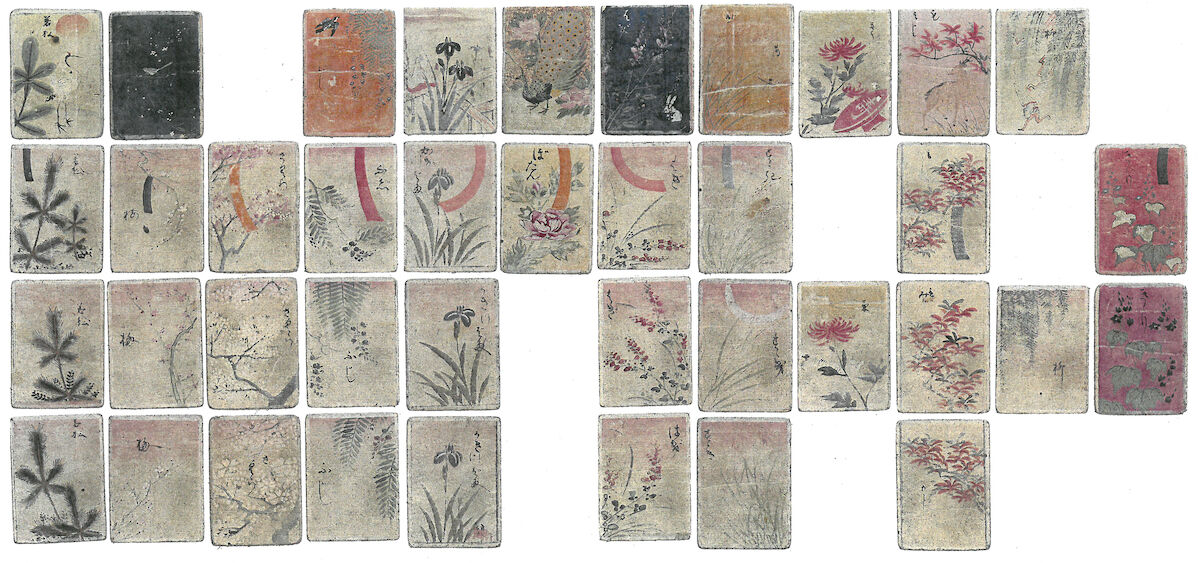

The two distinct schools of playing-card games first combined in the form of hana-awase (花合せ) decks. These early 18th century ancestors of Hanafuda (such as the deck pictured below) show a very regular configuration of cards for each flower, which evolved during the 18th and 19th centuries into the unusual configuration of the Hanafuda deck.

Some of the cards from a hana-awase deck produced circa 1704 (at least before 1710, according to Ebashi). This type of deck originally contained 400 cards but many are missing, and the extant set pictured here comprises cards from several different packs. Note the chrysanthemum with sake cup in the third card on the top row.

© 2019 JPCM, used with permission

While decks such as the above are obviously for a different style of game, most of the imagery that would become part of the hanafuda deck was already present.

Selecting only the 12 flowers used in hanafuda from the above hana-awase deck shows that most of the imagery that would become part of the hanafuda deck was already present. Note, however, the peacock with peony in the 6th month and the rabbit in the 7th, neither of which appear in hanafuda.

© 2019 JPCM, used with permission

While “virtually all major painting lineages produced cycles of birds and flowers of the twelve months”,L (127) it is unclear exactly where the specific imagery of the cards derives from. The most famous 12-month “cycle” which pairs animals and plants is that of the poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241),Teika’s pairings are: willow & bush warbler, cherry & pheasant, wisteria & skylark, deutzia & cuckoo, mandarin & moorhen, pinks & cormorant, maiden flower & magpies, bush clover & geese, eulalia & quail, chrysanthemum & crane, loquat & plover, and plum & waterfowl.L (127) There is perhaps more alignment with the school of artists who followed the Qing (i.e. Chinese) artist Shen Nanpin (c. 1682–1760), whose works became popular in Japan in the Edo period; note, for example, Ishizaki Gensho’s Flowers and Birds after Shen Nanpin with its pairing of the phoenix & paulownia tree.L (128–9) But even this is not a close match, and that particular combination is a feature of the Kanō school. It is perhaps worth noting that one hana-awase deck has been attributed to Kanō Hōgai (1828–88). but it does not correspond closely to the pairings which were selected for the deck.

Thus, at the moment it is not obvious exactly how the Hanafuda deck was developed from the hana-awase cards.I hope to expand on this in future! It seems that at some point an enterprising manufacturer began to produce a stripped-down version that Japanese Hanafuda scholar Ebashi Takashi (江橋崇) calls the Musashino (武蔵野) deck, which should perhaps be considered a pattern in its own right. But because of the illegality of gaming at this time, evidence is scarce.

Banning & Legalization

Some time after their introduction, Hanafuda games were restricted as part of a total ban on gambling introduced during the Kansei ReformsDuring the Kansei Reforms, gambling was prohibited by the 博奕賭ノ勝負禁止ノ儀ニ付触書, promulgated by Matsudaira Sadanobu on the 12th of January, 1788.M (p. 44) (1787–1793).

As a Dutch warehouse master living on Dejima in the 1820s wrote:N (202)

Alle kans- of waagspel, of het eigenlijk gezegde dobbelen, is ten strengste verboden; doch er zijn sommige plaatsen, waar dit in het verborgen geschiedt, want in het openbaar mag men noch dobbelsteenen noch speelkaarten vertoonen.

All games of chance or gambling, or properly speaking dicing, are strictly prohibited; but there are some places where this is done in secret, for in public one may show neither dice nor playing cards.

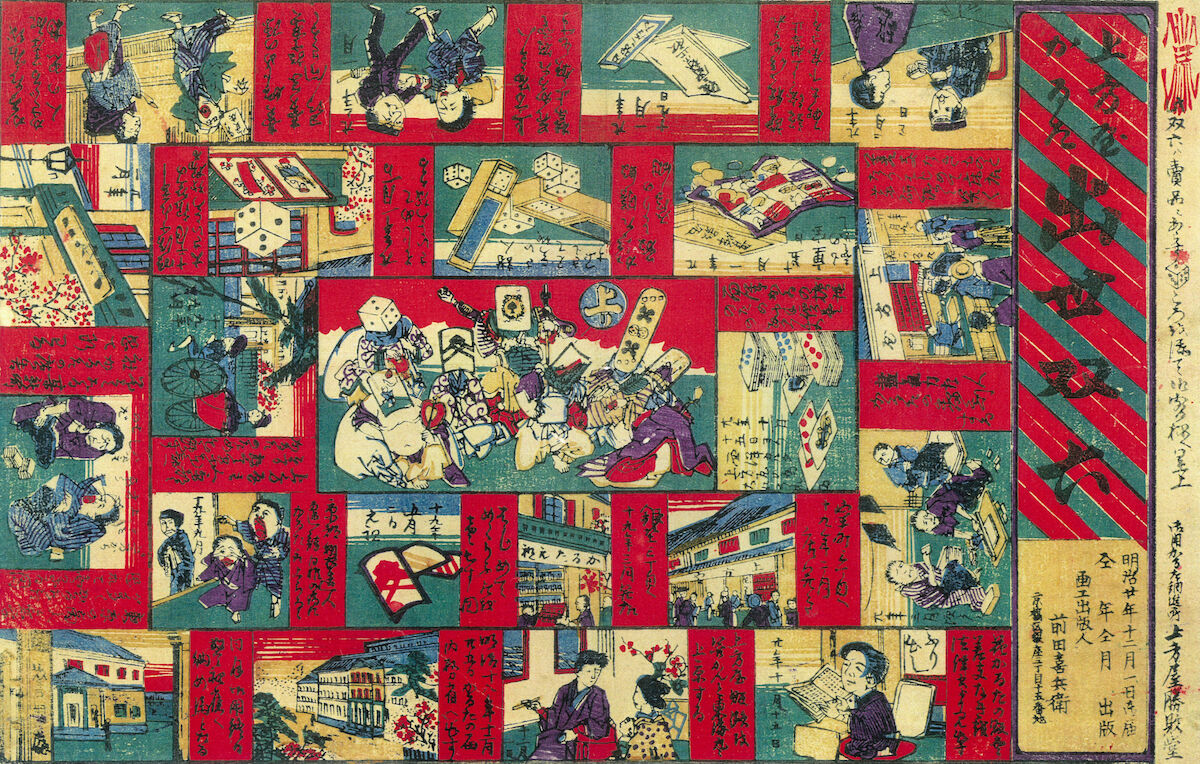

This ban was to remain in place for nearly a century. By 1885, the landscape began to shift, when a ban on Western playing cards (西洋かるた seiyō karuta) was lifted due to complaints from foreign officials.O (pp. 189–192) A bookstore owner in Ōsaka named Maeda Kihei (前田喜兵衛) took note.Kihei appears to have been something of a rogue: he is somewhat infamous in the philately community for selling collections of counterfeit stamps to unsuspecting tourists. Through his careful reading of legal texts he became convinced that the selling of Hanafuda was not actually explicitly prohibited. So, in December 1885 he moved to Tōkyō with a plan to open a shop openly selling Hanafuda cards.

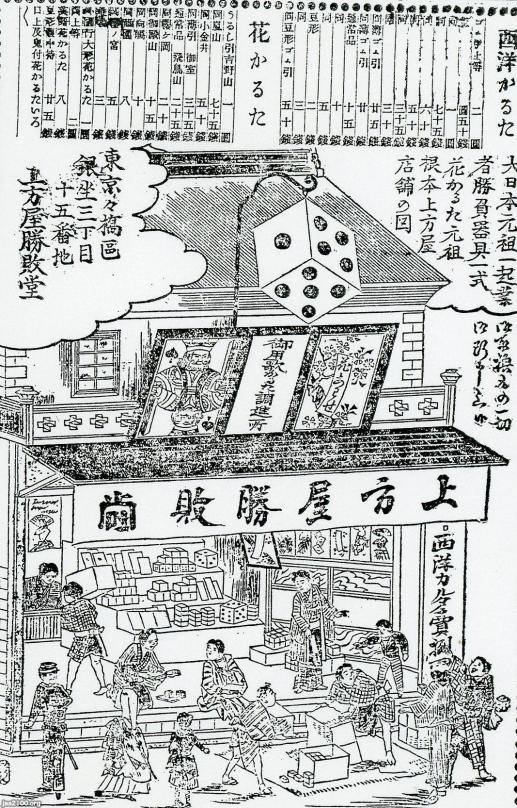

But Tōkyō was not so easily convinced. Local landlords refused to let to him, believing his proposed business illegal, and he was unable to convince newspapers to print his advertisements. In order to prove himself correct, he devised a cunning plan: he officially petitioned the Tōkyō police to ban the sale of Hanafuda. His petition was declined, the police stating that the sale of Hanafuda was legal. Armed with this confirmation, he opened his first shop later that month in the Yagenbori neighbourhood of Chūō district in Tōkyō (中央区薬研堀町, now part of Higashi–Nihonbashi). The shop was named “Kamigataya” (上方屋, ‘Kyōto region store’).O (pp. 189–192)P

Ever the promotor, at the end of 1887, Maeda published this sugoroku game based on the story of his struggle to open a store selling playing cards. The track spirals in a counter-clockwise direction to the centre of the board, where the final square (marked 上り) shows Japanese and Western cards and dice celebrating together.

© JPCM, used with permission

Success came quickly. A month later, Maeda opened a second branch of Kamigataya in Muromachi district (室町), and this was soon followed by a third store in Ginza (銀座) in March. To promote the opening of the Ginza store, Maeda also staged a Hanafuda-themed play in March 1886, which was held at the Chitose theatre (now called the Meiji-za).

Advertisement for Maeda’s play entitled 花合四季盃 (“Flower-matching four seasons sake cup”). The background shows an early form of Hanafuda deck. On left is Onoe Kikugorō V (五代目尾上菊五郎), on right Ichikawa Kuzō III (三代目市川九蔵) as Ono no Michikaze.

In addition to the retail stores, a specialized wholesale store was opened in the Ningyōchō street in the Sumiyoshi neighbourhood,Sumiyoshi-chō was an Edo-period red light district and the birthplace of the Sumiyoshi-kai yakuza organization.Q The area was destroyed along with most of the rest of Nihonbashi in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923; the location where Sumiyoshi-chō existed is now part of Nihon-bashi Ningyō-chō 2–chōme (人形町二丁目). in Tōkyō’s Nihonbashi district (日本橋住吉町人形町通り). Maeda later also started other stores with names that riffed on the original store, such as Nakagataya (中方屋) and Shimogataya (下方屋).P

In this early 20th-century postcard, another branch of Kamigataya can be seen on the left, identified by the large die; this one is in Motomachi in Yokohama.

A newspaper advertisement depicting the outside of the Ginza Kamigataya store, 1889. The large die was added to the store in December 1886.

The storefront of Nakagataya, as shown on a Hyakunin Isshu box.

Once the viability of Hanafuda had been proven, other manufacturers appeared quickly: the company that was later to become Nintendo began producing Hanafuda cards in 1889. Other companies such as Ōishi Tengudō claim to have been operating discreetly during the prohibition period; in their case behind the doors of a rice merchant named Minatoya (湊屋).R

Changing Attitudes

Even after prohibition had ended, Hanafuda retained a poor reputation, and gambling with the cards remained illegal. In 1892, Korekata Kojima (児島惟謙, 1837–1908), who was the head of Japan’s supreme court (大審院 daishinin), was accused along with five other supreme court judges of gambling with Hanafuda (弄花, rōka). Due to a lack of evidence, the case was dropped, but Kojima accepted ‘moral responsibility’ for the scandal and resigned his position.S (p. 813)

Despite this “image problem”, playing Hanafuda became part of what it meant to be a shinshi (紳士) — that is, a modern, worldly gentleman.The Japanese word shinshi had originally been coined to translate the English “gentleman”,T (p. 32–8) and was particularly associated with those who enthusiastically embraced Westernization during the Meiji period. The author Uchida Roan (1868–1929) is said to have joked:

紳士の資格は? 弄花と蓄妾と負債と奔走。

What are the qualifications of a shinshi? Gambling with Hanafuda, keeping a mistress, being in debt, and running about.

Another commentator remarked ironically that “if you can’t play skillfully with 48 flower cards, you can’t be a sōninkan [奏任官, a type of official appointed by the prime minister]”.

The author and politician Suematsu Kenchō (末松 謙澄) described the attitude at the time in his 1905 English-language book A Fantasy of Far Japan: Or, Summer Dream Dialogues (p. 176):

In times gone by no game of cards having any resemblance to gambling was played among the gentry; moral discipline forbade such. Since the introduction of European ideas, the rigidity of discipline has somewhat slackened and cards are now played to some extent. Nevertheless, people do not consider card-playing good taste. If they play they do so with some diffidence, somewhat in a similar way as smoking is done by ladies in European society nowadays.

However, despite his protestation in the book that “I do not care for playing at cards, but I know the methods”, he goes on to give a detailed account of the gameplay — far more than a casual observer would know!

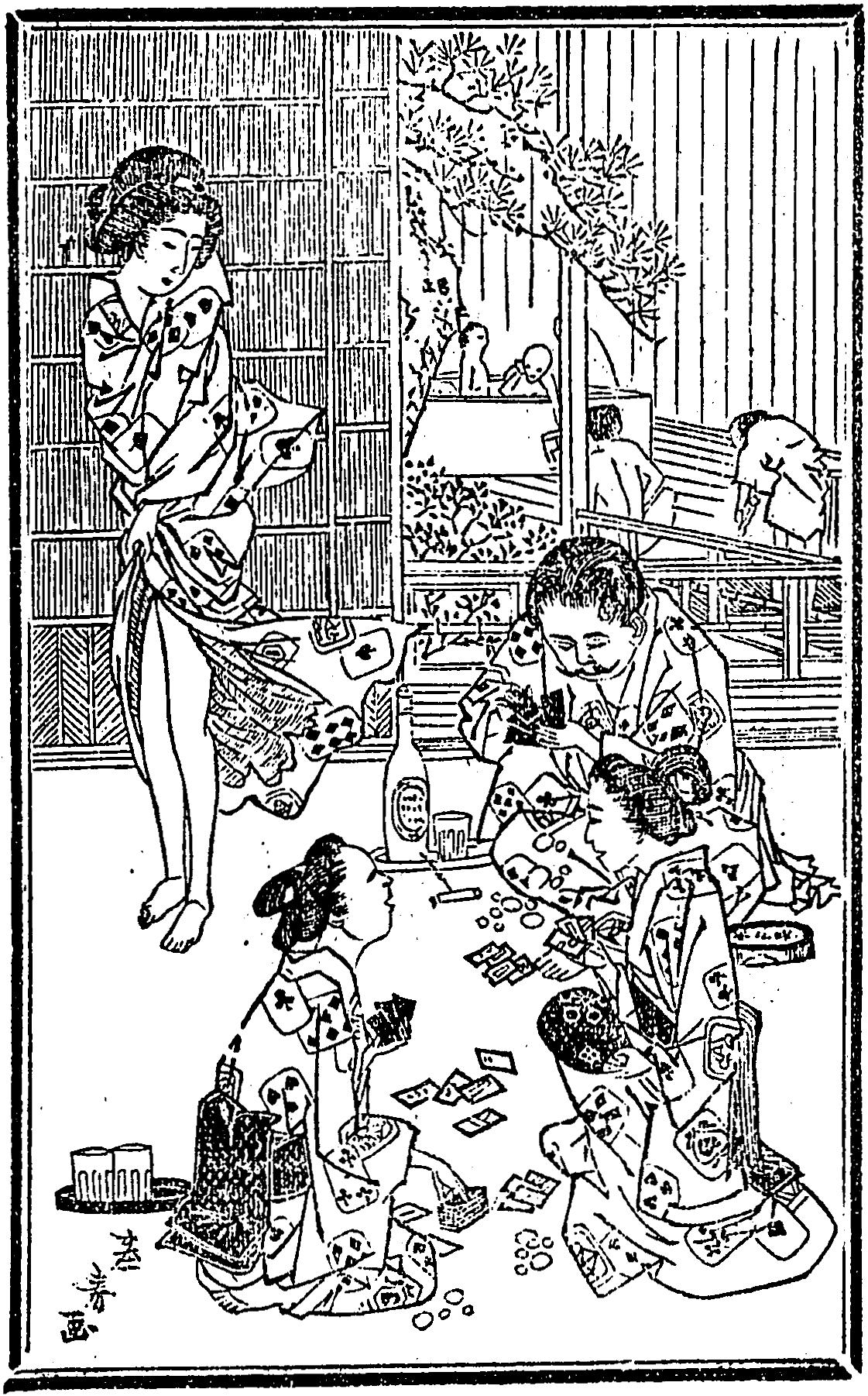

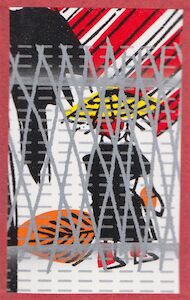

A Westernized gentleman playing cards with geisha, all of them wearing playing-card themed clothing. Note cigarette and ashtray.V (p. 25)

Apparently a family playing with Hanafuda cards.V (p. 13)

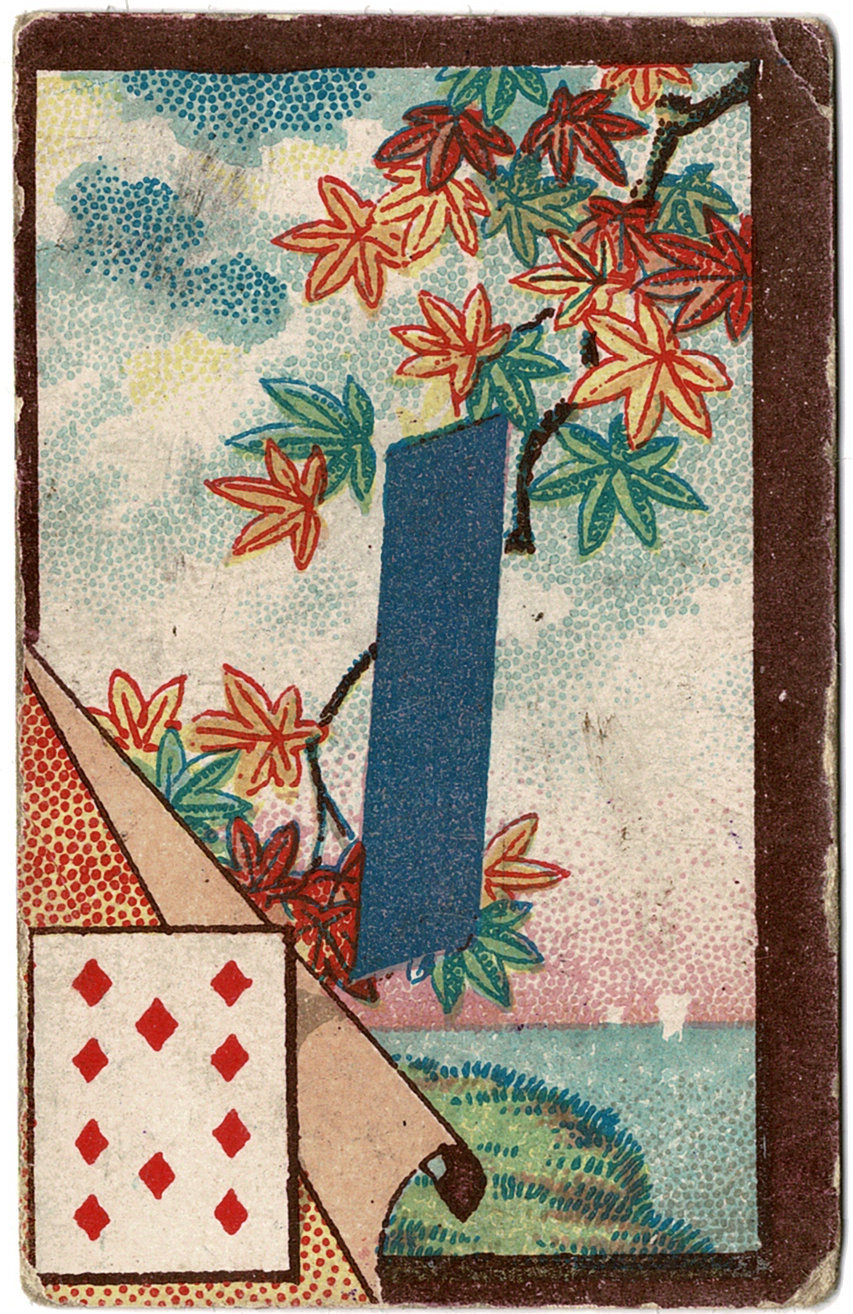

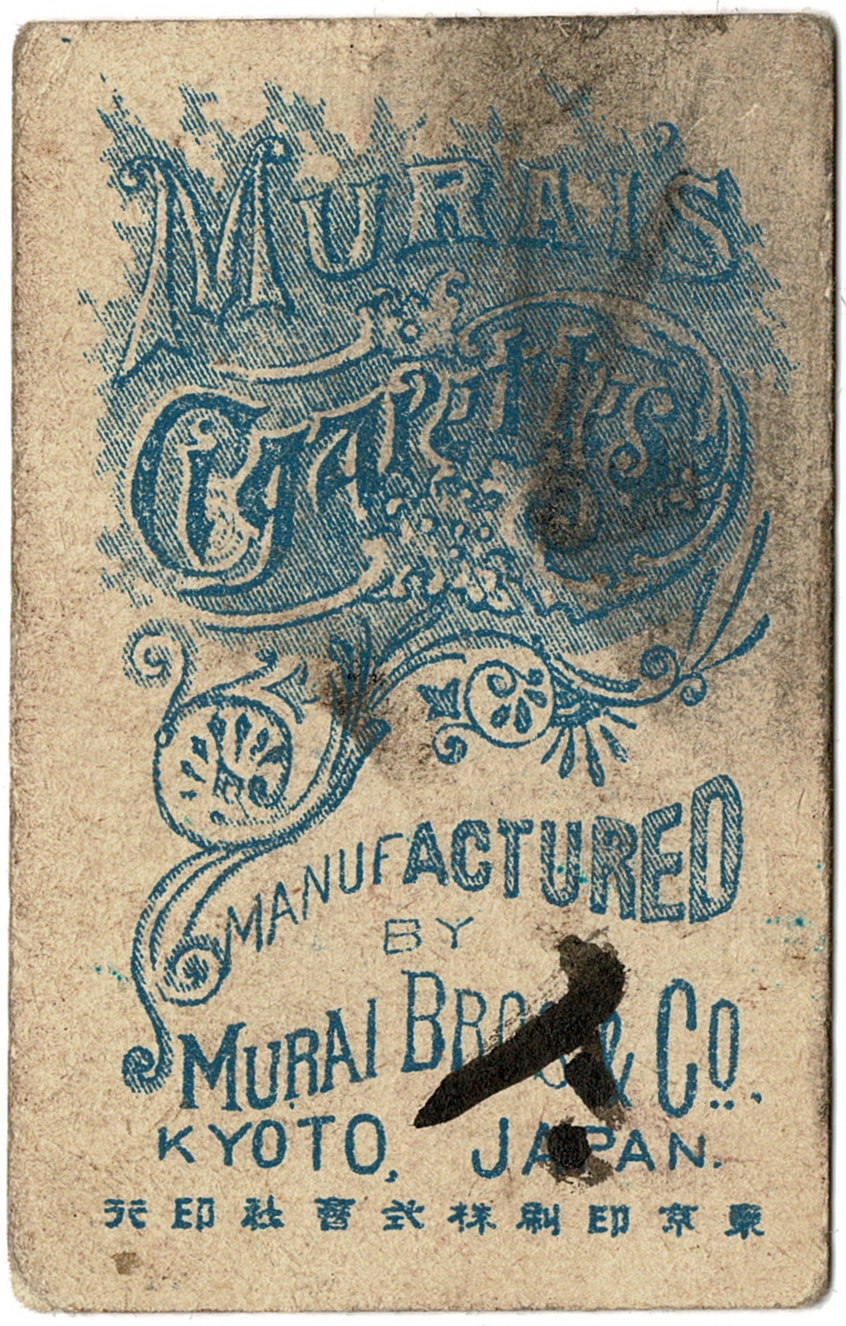

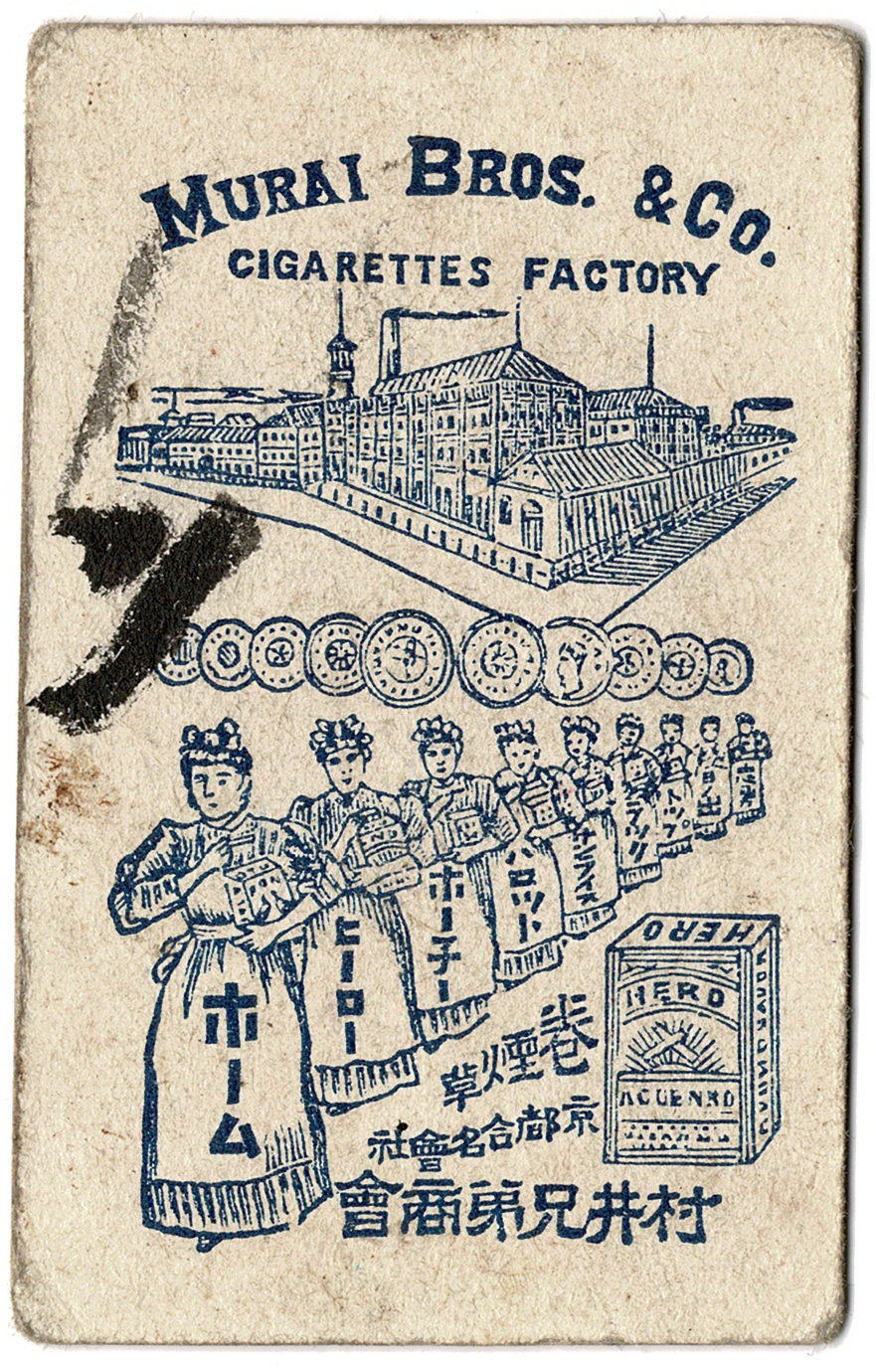

Another popularizing force during this period was that of cigarette manufacturers who began to include Hanafuda-patterned cards in cigarette packages as collectible items. The manufacturer Murai Brothers (村井兄弟商會, founded by the “tobacco king” Murai Kichibei (村井吉兵衛) in Kyōto in 1892) included tobacco cards which combined Hanafuda with Western playing cards. Murai was a progressive company that enthusiastically embraced Westernization across the whole of its business. They operated in conjunction with Western tobacco companies such as the British-American Tobacco Company, and many of their cigarette brands bore English titles. Where his competitor Iwaya would name a brand 日乃出 (hinode “sunrise”), Murai used the English name “Sunshine”.

In 1899, Murai formed the subsidiary “Tōyō Printing”In some sources this is given in its translated form as the “Oriental Printing Company”. (東洋印刷), and acquired printing equipment and training from the United States. With this equipment, they were able to produce high-quality packaging, and there is some suggestion that they worked with Nintendō to produce the first Western-style playing cards produced in Japan (1902).W Certainly, Nintendō’s early cards are often imitations of those produced by such US companies as the National Card Company which had been merged with the United States Playing-card Company in 1894.X

In 1904, the Japanese government nationalizedKichibei was compensated massively for being pushed out of the industry and later founded a bank, among many other enterprises.Y (p. 632) the manufacture of all tobacco products, and the Tōyō Printing subsidiary was taken over by British-American Tobacco.Z (p. 362)

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎Fronts and backs of combination tobacco cards produced by Murai Brothers, prior to 1904. The hand-written markings on the backs possibly indicate that they were adapted to be used as Iroha cards.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Traditional Methods of Manufacture

Before the mass-production era, Hanafuda cards were made by hand using traditional Japanese papermaking and printing techniques. The process was labour-intensive and required great skill.

Traditional types of paper made from fibres such as paper mulberry (kōzo)Not, as is often incorrectly repeated, cards “painted upon mulberry tree bark”, made of “mulberry paste”, or “from crushed mulberry bark”!AAAB (6)AC (103)ADAE (16)AFAG (6)AH (6)AI (26)AJ (3)AK (6)ALAM (9)AN (111) The best paper was made from the inner bark of paper mulberry, just as ‘normal’ paper is manufactured from wood such as pine — as if books are printed on “crushed pine”. (New Mythologies in Design and Culture (157) gets the distinction correct!) Neither, for that matter, did Nintendō founder Fusajiro Yamauchi create paper from scratch with the power of his “will”, as described in Game Over, Press Start to Continue (14) — which seems to be the original source that eventually transmuted into the mulberry-bark claim. were used in the construction process. Rougher, heavier paper was used for the internal core of the card, which would then be coated with higher quality white paper which had been printed with the black outlines using a woodblock press. Glue was also made heavier with the addition of powdered clay or stone, to give extra heft to the cards. After this, the colour of the cards was added using stencils and brushes, then the cards were cut and the rear of the cards back-pasted with contrasting paper, and the edges folded over. A final step in the process was to run the cards through a roller to polish them and provide the curvature expected by the players.

At the end of the Edo period, these cards were often manufactured by kuge nobles — the non-military aristocratic class which surrounded the court. Despite holding aristocratic rank they were often very poor:

Among the lower ranks of the Court Nobles, many were so poverty-stricken that they had to rely for subsistence on menial labour. One of the commonest kinds of such labour was the manufacture of hana-garuta and uta-garuta.AQ

Card-making offered these impoverished nobles a way to survive. The financial desperation of the family of Iwakura Tomomi (1825–83) — later to be one of the leading figures of the Meiji restoration — was such that they had even resorted to renting out their house as a gambling den.S (4)He himself was excluded from the grants mentioned in the just-cited article.

The tradition of hand-made cards would not survive long into the modern era. With rising taxation many of these enterprises would close or become consolidated into larger companies, and machine-produced cards would become the norm after the end of the second world war.

Taxation, Decline, and Revival

In 1902 a stamp duty was introduced that was inspired by similar taxes imposed in Western countries, the intent being to raise the cost of cards (and thereby discourage their use) but also to increase tax revenue. The tax imposed was crushing: 20 sen per set,The sen (銭) was a unit of currency representing 1⁄100 of a yen. in a time when cheap Hanafuda decks could be had for as little as 2–3 sen. The effect on card manufacturers was “dire”, as Rebecca Salter puts it.AR (p. 186) Ebashi states that the law led to the closure of many small producers, and made it much harder for new manufacturers to enter the industry; both due to the tax itself as well as onerous record-keeping and inspection requirements.AS

During this period, Nintendō managed to survive in part by taking up the manufacture of regional patterns of Japanese cards (地方札 chihōfuda), whose original, small-time, manufacturers had failed due to the new taxation law.AT

By the mid to late 20th century, interest in the game was waning. A poll by Japan’s Cabinet Office in 1956 indicated that only 9% of people played Hanafuda, compared with 28% who played with Western playing cards.AU Starting in the late 20th century, Hanafuda seems to have had something of a revival. “Character” decks featuring popular anime and manga characters began to be produced, and the popularity of Hanafuda has also been boosted by films featuring the cards, such as Summer Wars (2009).

While Japan produces many new types of Hanafuda cards, in Korea Hwatu games appear to be much more popular than their Japanese counterparts, and several films about gambling with Hwatu — most prominently the Tazza series (2006, 2014, 2019) — have been box-office successes.

Image search results on Instagram (as of writing in 2021) for the hashtags #花札 and #화투 showed about twice as many Korean-tagged images, despite Korea having only a third of the number of Instagram users that Japan has.AVAW The content of the images also gave many clues to the game’s popularity: Korean images often show games in progress, and many times being played for money, whereas Japanese images are often just of the cards themselves, focusing on their æsthetic value.

The Art of the Cards

The culture of the Edo period in which Hanafuda cards first appeared was heavily influenced by the aristocratic culture of the earlier Heian period. As such, the artwork on the cards abounds with references to Heian period literature, festivals, and artistic tropes:

With the exception of the peony, which entered the poetic canon in the Edo period, all the images are from classical poetry of the Heian period and reflect urban commoners’ knowledge of the poetic and cultural associations of the months.AX (loc. 1739–1741)

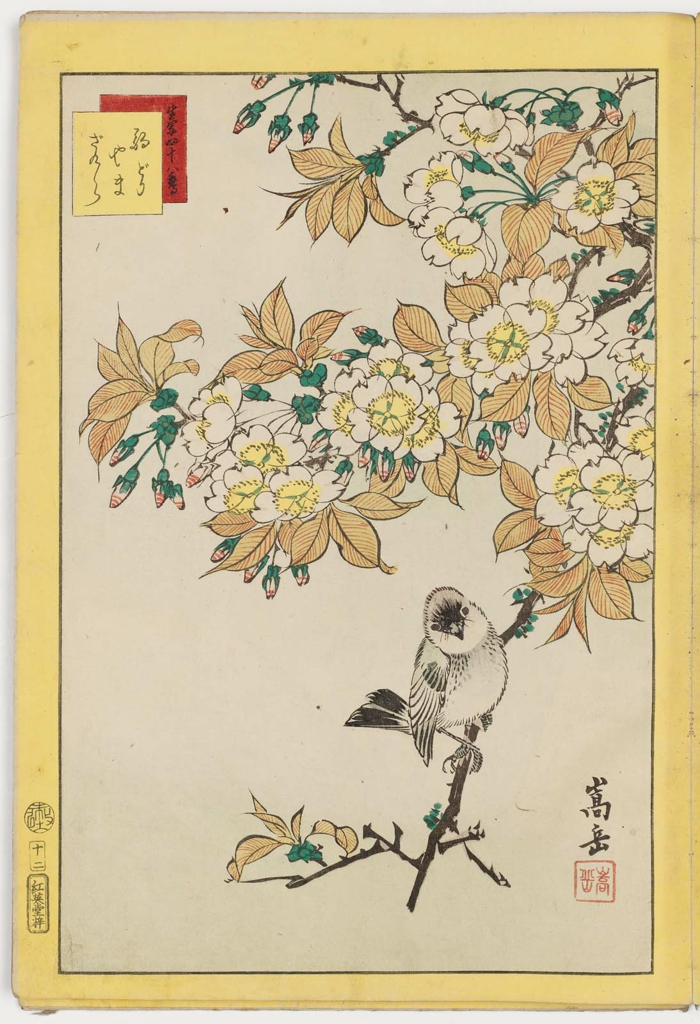

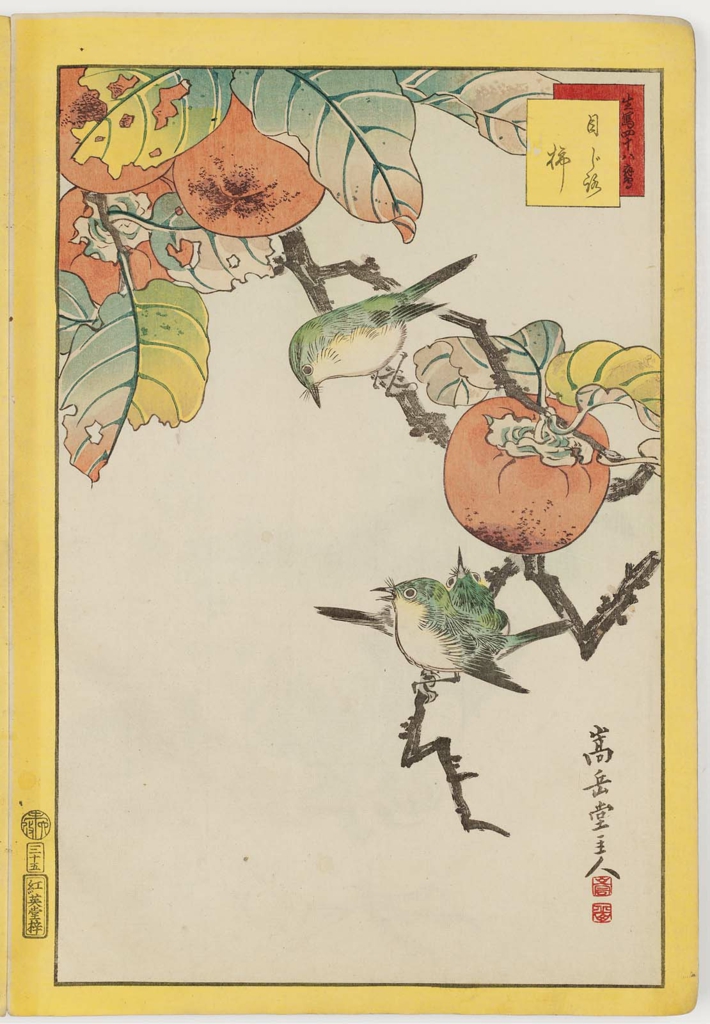

Artistically, the cards derive from the kachō-ga (花鳥画 ‘flower and bird image’) tradition. Artworks created in this style often have poems written upon them, and these appear on some cards of the Echigo-bana pattern.

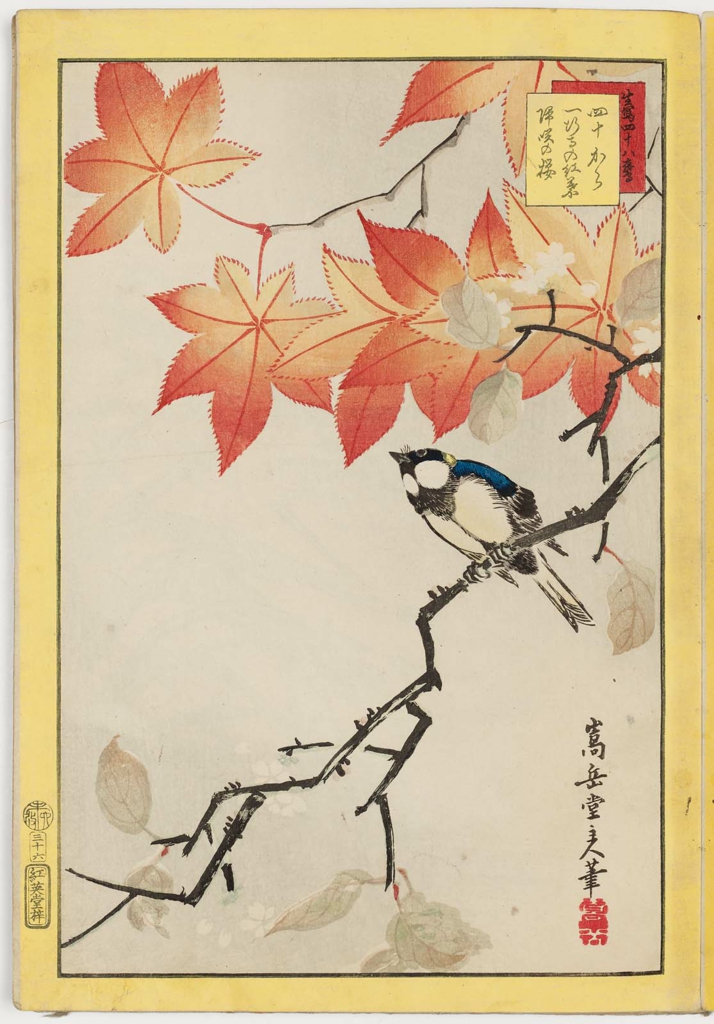

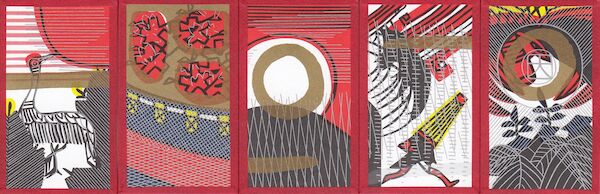

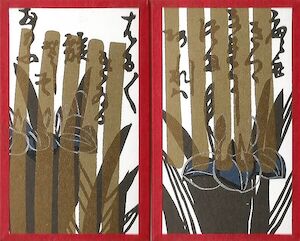

Art in the kachō-ga style: a selection of prints from the series Forty-Eight Hawks Drawn From Life

生うつし四十八鷹 (1859), by Nakayama Sūgakudō.

Hanafuda Patterns

A playing-card ‘pattern’ is a common set of designs that has been used by multiple different manufacturers over a period of time. With hanafuda there is now one primary or “standard” pattern: all other patterns are referred to as ‘local cards’ (地方札 chihōfuda), and are considered to be specific to a particular region. Most of these are of historical interest only and are no longer manufactured, and there is little information about how gameplay differed in different regions.

Standard (Hachihachi-bana)

The standard pattern is now one that is called hachihachi-bana (八八花/八々花), since it was primarily used to play the game 八八 ‘88’. Almost all decks use this pattern, and images from it are used to show the cards of each month below.

The 5 Bright cards of the hachihachi-bana pattern, from a Nintendo deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Korean deck differences

Korean decks are also based on the hachihachi-bana pattern, but the ribbons are usually blue instead of purple, and there is Korean text on the standard three red ribbons (labelled 홍단, hongdan ‘crimson ribbon’) and all three blue ribbons (청단, cheongdan ‘blue ribbon’).

Korean Hwatu cards with ribbons.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

There are also differences in the ‘rain man’ (see below), and depending on the deck, other aspects of the cards can also be translated into Korean cultural terms. For example, the lesser cuckoo of the Japanese cards is in some decks the Oriental magpie, which is the national bird of Korea.

The 무지개 (mujigae, ‘rainbow’) brand Hwatu deck (on left) features a Korean magpie (까치 kkachi), instead of the usual lesser cuckoo as shown on the Daiso Hwatu-format deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The ‘rain man’ wears traditional clothing in both Japanese and Korean decks. The Japanese man (left) wears a Heian period courtier’s daily outfit (狩衣 kariginu), with tall tate-eboshi (楯烏帽子) hat, and very tall rain-clogs (足駄 ashida) on his feet. The Korean man is wearing a noble’s gat (갓) hat, and an outer coat with very large sleeves.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Mushi-bana

The Mushi-bana (虫花 ‘insect flowers’) deck is a variant that contains only ten months, as it lacks the sixth (peony) and seventh (bush clover). It is especially used for playing the game of the same name, Mushi (‘insects’). It is sometimes described as a shortened version of a standard Hachihachi deck, but in reality, it originated as a distinct regional pattern.

Nintendō produced this pattern until recently, but it now appears to be extinct.

Nintendō’s Mushi pattern differs slightly from that of its standard deck.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Echigo-bana

The regional Echigo-bana (越後花 ‘Echigo flowers’) pattern is based on designs that are older than the standard pattern. The most obvious difference is that all the cards are overpainted with gold and silver in various patterns.

The 5 Brights of the Echigo-bana pattern, by Ōishi Tengudō.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Some of the kasu cards also carry short poems (短歌 tanka). Poetry is a common sight on traditional Japanese art — as seen on the kachō-ga prints above — and often provides more context to the images. The poems of the Echigo-bana will be examined in more detail below as part of examining the cards of the deck.

Echigo-kobana

The Echigo-kobana (越後小花 ‘Echigo small flowers’) pattern is similar to the Echigo-bana, but with very small cards measuring approximately 3 cm × 4.5 cm (1⅛″ × 1¾″).

The 5 Brights of the Echigo-kobana pattern, by Ōishi Tengudō.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Because of the small size, there are no poems on this deck. However, it does contain four extra cards. Any special rules for the deck, including the use of these extra cards, are unknown — the manufacturer Ōishi Tengudō even includes a note with every deck sold asking for anyone who knows the rules to contact them!

The four extra cards of an Echigo-kobana deck by Ōishi Tengudō.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

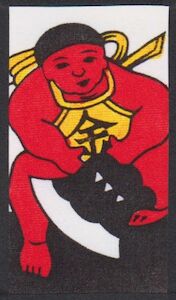

Awa-bana/Kintoki-bana

The Kintoki card, by Ōishi Tengudō. He is depicted carrying an axe and wearing a shirt with the character 金 (kin, ‘gold’) on it.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

This is another regional pattern called Awa-bana (阿波花) or Kintoki-bana (金時花). It originated in Awa province, in what is now Tokushima prefecture.

Like the Echigo-bana pattern, some of the Awa-bana carry poems (in fact, they carry the same poems). The deck also contains an extra card which features the titular Kintoki (金時), a legendary strong-boy also known as Kintarō.

The 5 Brights of the Awa-bana pattern, by Ōishi Tengudō.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Dairen-bana

Dairen-bana (大連花) is an extinct regional pattern from the city of Dalian (大连市) in China. It dates from the era of the Kwangtung Leased Territory, when Japan occupied the region from 1905 until the end of WWII. The pattern possibly existed as a way to reduce government taxation on cards, as cards sold in occupied regions did not attract the same level of tax as those sold within Japan’s own islands.

The main distinguishing feature of the pattern is that each type of tanzaku card has a unique background pattern (as opposed to the usual ‘confetti’). The remainder of the cards follow the standard pattern very closely.

Three cards showing the different backgrounds for each type of tanzaku card.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Modern/Novelty decks

In addition to the above, there are also many modern revisions or novelty decks that do not conform to any one of the traditional patterns. More information and examples of these can be found in the article about new Hanafuda manufacturers.

The Cards in Depth

Firstly, a short note about the ordering of the deck: while nominally the cards start in ‘January’, at the time the deck was created Japan’s calendar was based upon the lunisolar Chinese calendar, which started in what is now February. This explains why ‘March’ is the month of the cherry blossom when — according to the current calendar — it should be April,In Kyoto from the 11th to 13th centuries, the average peak of the cherry blossom season was April 17th.AX (loc. 484) and why ‘August’ shows the full moon when the full moon festival (月見 tsukimi) actually falls in September–October.

However, even with these modifications the eleventh (willow) and twelfth (paulownia) months seem to appear in the ‘wrong’ place. The willow cards also depict heavy rain and a frog, both of which are associated with summer.

In Korea, an altered ordering is used where the ‘November’ and ‘December’ months are switched, so that the willow cards come last. There is also another ordering used in Japan which might be called the “Nagoya ordering”, as it is used in several games from that region.Such as Tensho. This ordering (with differences in bold) is:

Pine

Willow

Cherry

Wisteria

Iris

Paulownia

Bush Clover

Miscanthus

Chrysanthemum

Maple

Peony

Plum

1月

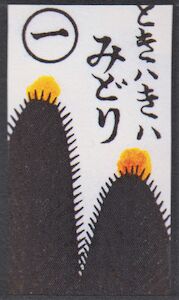

The cards for January feature pine trees. There is one bright card, one tanzaku card (with text), and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

An elaborate 19th century kimono with Mount Hōrai pattern: plum and pine trees with cranes, atop a large turtle.

The first month is represented by pine trees (松 matsu), which of all plants is most strongly associated with the Japanese new year. The pine is associated with winter and snow, so these cards show the lingering influence of winter during this period. The first week of the new year is known as the ‘pine week’ (松の内 matsu no uchi), and even today Japanese households are decorated with sprigs of pine at their entranceways in the form of the kadomatsu (門松 ‘gate pine’). A traditional festival that was held on the first Day of the Rat of the new year (子の日の宴 nenohi no en) involved nobles venturing out to uproot small pine trees.A (168)

The bright card shows a crane and pine trees, with the sun rising in the background. Both the crane and the pine are symbols of longevity. Their combination evokes the mythical Mount Hōrai, a dwelling-place of immortals, which is depicted as wooded with pine trees and populated by cranes.

The Japanese crane has a red crest.

© Shutterstock.com/Ondrej Prosicky: 1043519431

The poet Minamoto no MuneyukiMinamoto no Muneyuki (d. 983) was a poet of the Heian period, and named one of the ‘Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry’. (源宗于) captured the transitional period of the pine at the new year with a tanka presented at a poetry competition organized by the Empress during the reign of Emperor Uda. The Kokin Wakashū (古今和歌集 “Collection of Old and New Poems”) preserves this poem in its ‘Spring’ section (#24):

ときはなる

松のみどりも

春くれば

今ひとしほの

色まさりけり

Even the verdure

of foliage on the pine tree,

“ever unchanging”,

deepens into new richness

now that springtime has arrived.AY (p. 18)

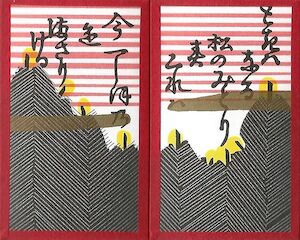

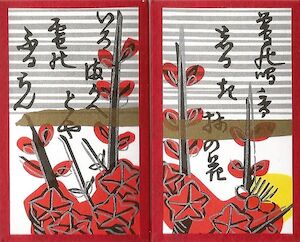

This poem appears on the kasu cards of the Echigo-bana pattern. The Awa-bana kasu also carries a shortened reference to this poem, announcing that spring is here:

とき𛂞き𛂞

みどり

常磐木は

緑

The unchanging tree

is green.

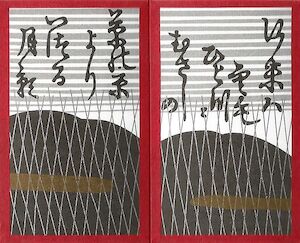

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

An Awa-bana kasu card, with a shortened version of the same tanka (the other kasu card bears the same phrases).

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

An old pine tanzaku card with inscription reading urasu (宇良す), the name of a Hachi-Hachi yaku. Produced by 現〇商会.

© JPCM, used with permission

The text on the tanzaku reads akayoroshi あ𛀙よろし.The writing on the tanzaku uses a rare hentaigana character for ka, which is usually written か. It may not render correctly on your device. This means ‘red is good’ and was an older name of a Hachi-Hachi yaku (scoring combination) which is now called akatan.The meaning of this phrase is usually said to be “unclear”, even by Hanafuda manufacturers. Some derive a meaning like ‘clearly good’ based on reading aka as a short form of akiraka ni (‘clearly’). However, old listings of yaku show akayoroshi alongside aoyoroshi (‘blue is good’) indicating that aka should be read straightforwardly as 赤 (‘red’). Cards from vintage decks can carry older names for this yaku, such as urasu, or sometimes simply 正月/初月, indicating the first lunar month.

2月

In reality, the bush warbler is not a brightly-coloured bird.

© 2015 Eric Gropp, 🅭🅯

The cards for February feature plum trees in blossom. There is one tane card, one tanzaku card (with text), and two kasu cards. The text on the tanzaku is the same as that on January’s.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

The second month is represented by plum trees in blossom (梅 ume), paired with the bush warbler (鶯 uguisu). This combination has announced spring in Japanese poetry since the Man’yōshū (万葉集 ‘Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves’) was compiled in the 8th century (Nara period, after 759).AX (loc. 978) The bush warbler was praised for its song, and one of its cries is said to repeat hō-hoke-kyō, the Japanese name of the Lotus Sutra (法華経 hokekyō).

The plum blossom enjoyed a privileged position in early Japanese culture. Despite being a tree introduced from China, the plum blossom was the favoured flower in poetry and art during the Nara period; the native cherry blossom would only become more popular during the Heian period.AX (loc. 997) This shift was also visible literally: after a famous plum tree that was planted by Emperor Kanmu at the imperial palace had died, Emperor Ninmyō replaced it with a cherry treeThis cherry tree has been replanted several times since then, and is called the sakon no sakura (左近桜 ‘left-side cherry’). in 834.BA (p. 301) But the plum retained its place as the first of the year’s new blossoms, blooming even as the snow still lingered.

The first cry of the bush warbler announced the arrival of spring as surely as the flowers, as the poet Ōe no Chisato (大江千里) expressed during a competition in the Kanpyō era (889–898):

うぐひすの谷よりいづるこゑなくは春くることをたれかしらまし

Without the voice of the warbler that comes out of the valley, how would we know the arrival of spring?AX (loc. 952)

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The poem on the Echigo-bana kasu cards (the origin of which is unknown) also describes the call of the bush warbler. Note that while the poem must be describing white plum blossoms (白梅 hakubai), all Hanafuda patterns depict red plum blossoms (紅梅 kōbai), which became more popular later on:

鴬の

鳴音はしるき

梅の花

色まがえとや

雪の降るらん

The nightingale’s

Song is clear

And the white plum blossom

Becomes lost

In the falling snow.AZ (p. 99)

3月

The cards for March show the famous cherry blossoms of Japan. There is one bright card, one tanzaku card (with text), and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Third Month: Blossom-Viewing in Askukayama三月飛鳥山花見 by Kitao Shigemasa (北尾 重政, 1739–1820).

The Yoshino mountainside with cherry trees in bloom.

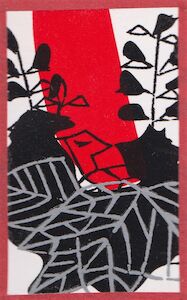

The third month is represented by cherry trees in bloom (桜 sakura). Blossom-viewing (花見 hanami), particularly of cherry blossoms, is a custom that dates back to the Heian period. The curtains (幕 maku) that are shown on the bright card are there provide privacy whilst viewing cherry blossoms. An example of their use can be seen in the image on the left. It was common to use striped fabric, particularly in red & white, while nobility would use curtains bearing their family crest.

The tanzaku of the March cards reads miyoshino みよしの ‘beautiful Yoshino’,Some older cards spell this phrase differently, some examples are: みよし𛂙, 美よし𛂙, or みよし𛂜. Other phrases seen on the cherry tanzaku include す𛀙𛂦𛃰 (すがわら sugawara), or 宇良す (うらす urasu). Both of these are references to the Hachi-Hachi yaku ‘うらすがわら’ (urasugawara). which is a sobriquet for the mountainous area of Yoshino (吉野) in Nara prefecture, famous for its cherry blossoms. The term miyoshino is often used to refer to this location in the imperial poetry collections.

In 1688, Matsuo Bashō (松尾芭蕉), Japan’s most celebrated composer of hokku, visited Yoshino during his travels but found himself unable to compose even a single poem. Despite the mountainside being covered in cherry blossoms, he was overwhelmed by the pressure of trying to live up to his predecessors.BB (p. 84) One of them, Yasuhara Teishitsu (安原貞室), had composed what Bashō considered to be the “finest hokku ever written”:BC (p. 8)

Look at that! and that!

Is all I can say of the blossoms

At Yoshino mountain.

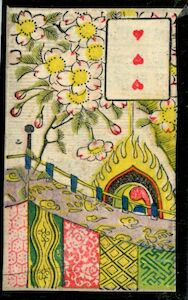

Rather than hanami, some older non-standard designs depict a bugaku (舞楽) scene, featuring a special large drum that is decorated with a flame motif (known as a 火焔太鼓 kaendaiko).

A bugaku scene from a combination card produced by Tenguya Tsutida.

© WCMPC, used with permission

A bugaku scene from a non-standard card by an unknown manufacturer.

© JPCM, used with permission

A bugaku scene from a mid-Meiji deck by Arakawa Fujibei (荒川藤兵衛). Another subtle detail are the yukitsuri at top right.

© JPCM, used with permission

4月

The cards for April show the drooping branches of wisteria. There is one tane card, one red tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Wisteria in bloom.

The fourth month is represented by wisteria (藤 fuji), its cascading purple blooms paired with the lesser cuckoo (ホトトギス hototogisu). Together they mark the transition from spring to summer: the cuckoo is a bird of summer,AX (loc. 1065) while wisteria is associated with the passage of spring into summer;AX (loc. 1021) it is also known as the ‘two-season plant’ (二季草 nikisō).

Like the bush warbler and spring, the first cry of the cuckoo was considered to announce the beginning of summer. By the time of the Edo period, this was perhaps more of a poetic dream than reality; the poet Buson remarked that he had only heard the bird twice, despite living in Kyoto for 20 years.BC (56)

The cuckoo swooping in front of the moon is a common motif in Japanese art. It is tempting to claim that this may be a reference to the tale of Yorimasa from the Heike Monogatari,BD (pp. 161–3) but the oldest decks do not have a moon on this card.

These cards are also nicknamed ‘black bean’ (黒豆 kuromame), due to their appearance, and in contrast to the ‘red bean’ cards of the 7th month.

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The tanka on the kasu cards is similar to Poem 135 from the Summer section of the Kokinshū,The poem on the card differs slightly in that the last line starts with ima ya 今や instead of itsu ka いつか.AZ (p. 100) perhaps written by Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本 人麻呂. The poem again focuses on the transition from spring (represented by wisteria) to summer (represented by the arrival of the cuckoo):

わがやどの

池の藤波

さきにけり

山郭公

いつかきなかむ

At my home

On the pond wisteria waves

Are breaking:

Mountain cuckoo,

When might you come and sing?

BE

Cascades of flowers

bloom on the wisteria

by my garden lake.

When might the mountain cuckoo

come with his melodious song?

AY (p. 40)

In Korean contexts, the non-tane wisteria cards are almost always shown upside-down, so that the plants are presented in the same manner as the bush clover in the seventh month. The cards are also referred to as 흑싸리, “black bush clover”, possibly because wisteria is not native to Korea. The tane card is never shown inverted.

5月

The cards for May depict iris flowers. There is one tane card, one red tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

The fifth month is represented by iris (菖蒲 ayame); a nickname for the month is negi (葱, ‘scallion/leek’).BG

The bridge shown on the tane card is a reference to the ‘eight bridges’ (八橋 yatsuhashi) featured in an episode of the Tales of Ise ( 伊勢物語 Ise Monogatari), in which the unnamed protagonistTraditionally this is presumed to be the poet Ariwara no Narihira (在原業平). of the story comes across a braided river that is crossed by overlapping planks forming a zig-zag bridge. Challenged to compose a poem on the subject “a traveller’s sentiments”, he recites the following:

からごろも

きつつなれにし

つましあれば

はるばるきぬる

たびをしぞおもふ

I have a beloved wife,

Familiar as the skirt

Of a well-worn robe,

And so this distant journeying

Fills my heart with grief.BH (pp. 74–5)

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

This poem, which appears in full on the kasu cards of the Echigo-bana pattern,AZ (p. 100) is in the form of an acrostic; the first letters of each line spell out kakitsuhata かきつはた, which is the name of the Japanese iris (杜若 kakitsubata).Note that at the time this poem was written, written Japanese did not distinguish between は ha and ば ba. Because of this scene, the iris and the planked bridge have a long association in Japan.

Irises at Yatsuhashi

八橋図屏風

A pair of screens by the artist Ogata Kōrin (尾形光琳, 1658–1716)

6月

The cards for June show peony flowers. There is one tane card, one blue/purple tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Tree peonies (牡丹 botan) mark the sixth month — large fragrant flowers which arrived late to Japan’s poetic tradition, imported from China in the 8th century.BI (p. 159)

While in China the peony was revered as the ‘king of flowers’, in Japan it was considered to be almost too bold for poetry. Those poems which do exist usually mention its striking colour, size, or Chinese origins.

A poem by one Kanchō (管鳥, d. 1818) included in the collection Akegarasu (明烏, 1773, edited by Kitō and Buson):

唐音も少しいひたき牡丹哉

the peonies bloom:

I wish I could speak

a little ChineseBJ

It is also known as the ‘queen of a hundred flowers’ (百花の王) and often paired with the lion — the ‘king of a hundred beasts’ (百獣の王). But on the cards, the peony is shown alongside a butterfly.

Ambivalence toward the flower persisted well into the Edo period. The poet KyorikuOr Kyoroku; accidentally given as “Hyoroku” in The Flowers And Gardens Of Japan (160). (許六, a student of Bashō’s, d. 1715) wrote in a series of poems comparing flowers to women (1704):BK

牡丹は、寵愛時を得たる妾の、天下にはゞかれる、心なげに打ちほこり、常は嫉妬我執のいかりふかくして、靑天にむかつて吐息をつきたる風情に似たり。

The tree peony is like a favoured concubine, revered throughout the land, who carries herself with a carefree pride, yet whose heart is ever filled with deep jealousy and attachment, sighing towards the blue heavens.This is, unfortunately, a machine translation.

Buson (1716–84), perhaps with Kyoriku’s poem in mind, wrote instead (1780):

“Ready to breathe forth a rainbow” is an idiom referring to someone who is buzzing with energy. But Buson’s most famous poem on the peony refers to the end of the flowering season (1769):

With the fall of these petals, the season of the peony ended, and we again return to Japan’s native flora.

7月

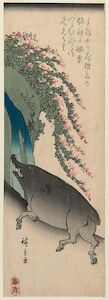

This print by Hiroshige featuring a boar and bush clover shows a remarkably similar form to that of the boar card.

The cards for July show bush clover. There is one tanzaku card, one red tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Bush clover in bloom.

© 2020 Atsuhiko Takagi , 🅭🅯🄏⊜

The seventh month is represented by bush clover (萩 hagi). Players also nicknamed the cards ‘red bean’ (赤豆 akamame/小豆 azuki) due to their imagery. Bush clover is very strongly associated with autumn — the Japanese character 萩 is a composition of 秋 ‘autumn’ and 艹 (full form 艸) ‘grass’.

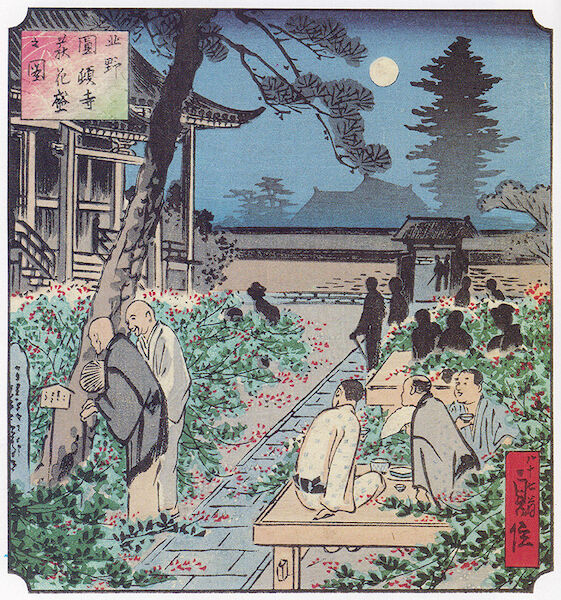

People viewing hagi flowers at Taiyū temple (太融寺), by Hasegawa Sadanobu (長谷川貞信).

Bush clover is also (along with miscanthus, see the next month) considered one of the “seven flowers of autumn” (秋の七草), a term which derives from a pair of poems in the Man’yōshū (book 8:1537–8):BM (p. 212)

The flowers that blow

In the autumn fields

When I count them on my fingers,

There they are—

The flowers of seven kinds.

They are the bush-clover,

The ‘tail flower’, the flowers

Of the kuzu vine and patrinia,

The fringed pink, and the agrimony,

And last the blithe ‘morning face’.

The bush clover is referred to in the Man’yōshū even more than the plum or cherry blossoms.BN (p. 54)

On the other hand, the wild boar pictured on the tane card does not feature in any of the imperial poetry collections. As a representative of rural life, it was considered to be outside the boundaries of the aristocratic worldview of the poets. For the common people, however, the boar was very important as a source of food. When Emperor Tenmu banned the consumption of meat in 675, only cattle, horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens were prohibited.AX (loc. 4261) Wild game such as boar and deer were not included: either they escaped the imagination of the Emperor, or they were too important as food sources for commoners.

8月

The cards for August show waving fields of miscanthus, also known as silvergrass. There is one bright card, one tane card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Miscanthus plumes.

The eighth month is represented by miscanthus or silvergrass (芒/薄 susuki). It can also be called tsuki (月, ‘moon’),BO (p. 194) or oka (丘 ‘hill’).BP (p. 107)

The bold moon card is possibly the most well-recognized of all hanafuda cards. It is the standard card chosen as a representative emoji: 🎴 On printed cards, the fields of grass are often simplified into solid black circles. Because of the resemblance of this to the head of a bald man, another nickname for this month is ‘baldy’ ( 坊主 bōzu), a slang term for a Buddhist monk.

Traditionally, the most important date of the year for moon viewing was the 15th day of the 8th month (中秋観月 chūshū kangetsu);A (p. 176) the full moon always fell on the 15th due to the way the calendar was constructed.A (p. 170)

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

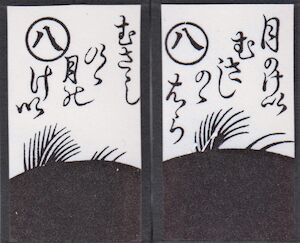

Awa-bana kasu cards, with reduced form of the tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Fairbairn (1986) says that the poem on the Echigo-bana kasu cards is “untranslatable”, because it has been corrupted, but that it is based on poem 422 of the Shin Kokinshū:

行く末は

空もひとつの

武蔵野に

草の原より

出づる月影

Its destination:

The skies, one with

Musashi Plain, where

From among the fields of grass

Emerges moonlight.

BQ

The Awa-bana kasu carry a shortened version, with the two cards carrying mirror versions:

月のけ𛀆

むさしのゝ𛂦ら

むさしの〻

月𛂜け𛀆

月の景

武蔵野の原

武蔵野の

月の景

View of the moon: Musashino plain

Musashino’s view of the moon

Famous places in the provinces: Musashi Plain

諸国名所 武蔵野

A woodblock print by Totoya Hokkei (魚屋 北渓, 1780–1850)

9月

The cards for September show chrysanthemums. There is one tane card, one blue/purple tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

The ninth month is represented by chrysanthemum (菊 kiku). The tane card depicts a sake cup, which is an implement of chōyō 重陽, the chrysanthemum festival, which is held on the 9th day of the 9th month. Because chrysanthemum blooms for a long time, it had become a symbol of long life in China, and the festival was introduced into Japan by the court of Emperor Kanmu (桓武天皇, 735–806).AX (loc. 1214)

During the festival, chrysanthemum petals are added to sake and consumed. The sake cup (杯 sakazuki) pictured on the card has the character 壽/寿 (kotobuki), meaning ‘long life’, written on it in a cursive script.

A poem by Bashō commemorates the evening of the 9th day of the 9th month, in 1691. He was staying at the temple Gichu-ji (義仲寺) in a hermitage known as ‘nameless hut’ (無名庵 Mumyō-an), when his disciple Kawai Otokuni (河合乙州) came to visit him with a gift:

草の戸や日暮てくれし菊の酒

this grass door—

dusk arrives with a present

of chrysanthemum sakeBS

The Imperial Seal of Japan.

2006 Philip Nilsson, 🅮

Chrysanthemums were also prized for their secular beauty, and collectors competed to breed particularly beautiful varieties.

The chrysanthemum is also used as a symbol by the Emperor of Japan. It was first adopted by Emperor Go-Toba (r. 1183–1198), but was not restricted to this purpose until the Meiji period. In modern times a stylized version of the chrysanthemum flower is used as the Chrysanthemum Seal (菊紋 kikumon), which is the crest of the Emperor of Japan (who uses a 16-petal version) and other members of the imperial family (who use a 14-petal version).

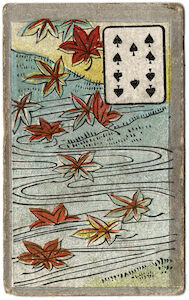

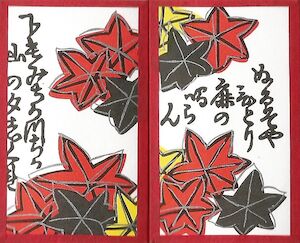

10月

The cards for October show fallen maple leaves. There is one tane card, one blue/purple tanzaku card, and two kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Maple trees along the banks of the Tatsuta-gawa in autumn.

© 2010 663highland , 🅭🅯🄎

The tenth month is represented by autumn leaves/maple (紅葉 momiji/kōyō). The tane card features a deer who is looking back over its shoulder, sometimes inspecting a twig. A reference to this card, the ‘10-point deer’ (鹿十 shikato) has thus become a slang term shikato (しかと) meaning to ignore or neglect.

The poet Narihira gazes at leaves floating on the Tatsuta river. The print features one of his poems about the river from the Hyakunin Isshu.

This Murai Brothers tobacco card shows maple leaves floating on water.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

While the leaves on the tane card are attached to a tree, the leaves on the other cards appear to be floating on water. This could be a reference to the Tatsuta river (竜田川), which was as famous for autumn foliage as Yoshino was for cherry blossoms in the spring.AX (loc. 1756) A anonymous poem from the Kokinshū (V: 283) celebrates the leaves floating on its surface:

龍田河も

みぢみだれて

流るめり

わたらば錦

なかやたえなむ

Beautiful is the Tatsuta

With Autumn’s brightest weaving;

If I cross the stream,

Alas! the brocade will be rudely rent.BT (p. 43)

Echigo-bana kasu cards, with tanka.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The poem on the Echigo-bana kasu cards is Poem 437 from the ‘Autumn 2’ section of the Shin Kokinshū. It was composed by Fujiwara no Ietaka (藤原家隆, 1158–1237), upon the finalization of the poetry collection:BU (p. 318)

したもみぢ

かつちる山の

ゆふしぐれ

ぬれてやひとり

鹿のなくらん

From the lower branches

Maple leaves scatter

In Autumn showers on the mountain.

Is it because he is wet

That the lonely stag is belling?

11月

The cards for November show willow trees. There is one bright card, one tane card, one red tanzaku card, and one kasu card.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

The eleventh month is represented by willow (柳 yanagi); it is also often referred to as ‘rain’ (雨 ame) or ‘drizzle’ ( 時雨 shigure).

These cards have a strange relationship with the other cards — in many games they have special powers, or they are valued lower than the cards of other months. For example, the bright of November will often score less than the other four Brights, and in some games the “lightning card” has special powers, such as being able to match any other card.

The scene shown on the Bright card depicts a famous Japanese parable: the man is the poet Ono no Michikaze (小野道風), considered to be one of the founders of Japanese calligraphy. After seven repeated failures to achieve a promotion, Michikaze was considering abandoning his attempts. One day, walking beside a stream, he saw a frog attempting to jump onto a willow branch. Seven times it jumped, and seven times it failed. On the eighth attempt, the frog reached the branch successfully. Michikaze was thus inspired to persevere with his attempts.BX (pp. 86–7)In Scottish folklore, the similar story of Robert the Bruce seeing a spider attempting to weave a web relates the same moral lesson.

On older decks, a different “rain man” is pictured. On these cards, the man is running in the rain with the umbrella closed around his head. This feature is preserved in the Echigo-bana pattern.

The Echigo-kobana “rain man” appears to be some kind of animal.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

On the Echigo-kobana’s “rain man” card, the figure has a bushy tail and appears to be either a kitsune, a Japanese fox/spirit; or a tanuki, the raccoon-dog. I am not sure of the significance of this.

The “lightning card” mentioned above is the red-coloured kasu card, which is usually called the ogre card in Japanese (鬼札 onifuda). The drums, which are visible in some patterns, are an attribute of the thunder god Raijin (雷神).

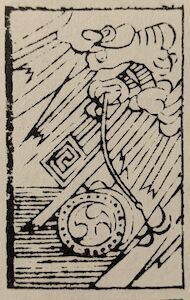

In this Ōtsu-e, Raijin attempts to recover his drum.

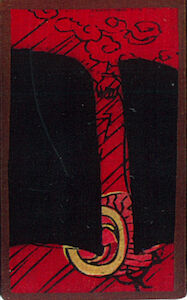

In some older decks, the Lightning Card depicts a scene derived from Ōtsu-e prints (大津絵), where Raijin is attempting to ‘fish’ back a drum that he has dropped. Remnants of this design can be seen in many decks of the standard pattern.

A dramatic fishing scene, from The Devil’s Picture-Books.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

A key-block print of the Raijin scene, from [BZ].

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

A card with hook visible at bottom, from a deck by Hakamada (袴田).

© JPCM, used with permission

12月

The cards for December show paulownia flowers. There is one bright card and three kasu cards.

© 2021 Louie Mantia, 🅭🅯🄎

Flowers of the paulownia tree.

The paulownia crest was most famously used by the Toyotomi family.

The twelfth month is represented by paulownia (桐 kiri). This is a tree that flowers in spring, and has large heart-shaped leaves.

The paulownia as a symbol was originally used by the imperial family and ranked second only to the chrysanthemum. Permission to use the paulownia was granted by Emperor Go-Daigo to AshikagaTakauji, whose descendants used it until the end of the Ashikaga shogunate in 1573. After this, Emperor Go-Yōzei granted use of the crest to ToyotomiHideyoshi (1537–1598), the second of the three “Great Unifiers” of Japan, and today it is most strongly associated with the Toyotomi family. However, as Toyotomi in turn allowed its use by so many of his allies, it is also now the most common crest in Japan.

In modern times, the paulownia symbol is also associated with the government. This use started after the Meiji restoration, and it appears on the seal of the prime minister’s office. There are many versions of the crest, with the 3–5–3 flower version being the most common. The 5-7–5 version is of higher standing and is the one used by the government.

The wood of the paulownia is light and strong and often used for boxes; it is very fast-growing and also somewhat fire-proof, so was useful as a storage material. Older high-quality Hanafuda decks came encased in an outer box of paulownia wood. The manufacturer Ōishi Tengudo still boxes many of their decks in this way.

Phoenix and Paulownia Tree

桐に鳳凰

by Isoda Koryūsai (礒田 湖龍斎, 1735–1790)

The phoenix (鳳凰 hōō, or fènghuáng in Mandarin Chinese) featured on the bright card is from Japanese mythology, and was traditionally associated with the empress of Japan. According to legend, the phoenix will only land on a paulownia tree. What appear to be ‘spikes’ on the card are really its long tail feathers. This card is sometimes casually referred to as the “rooster” card.

One of the kasu cards is usually coloured, often yellow, but sometimes with red as well. In some games it becomes a tane card, or even a tanzaku card.

One of the Paulownia cards of the Echigo-kobana pattern has a tanzaku.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The yellow-coloured kasu of the Awa-bana pattern is marked with the red clouds that usually indicate a tane card.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Usually (in Japanese decks) the manufacturer’s mark is on the coloured kasu card, much like the ace of spades is used in European decks. In Korean decks, the mark can also be on the full moon card or the jokers.

References

Morris, Ivan (). The World of the Shining Prince. Penguin Books: Middlesex, England, UK. ISBN: 0-14-005479-0. First published in 1964.

McCollough, Helen Craig (). Brocade by Night: “Kokin Wakashu” and the court style in Japanese classic poetry. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA. ISBN: 0-8047-1246-8.

Anderson, Jennifer Lea (). An Introduction to Japanese Tea Ritual. SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-0-7914-0749-3.

Dalby, Liza (). ‘Kai-awase: the shell-matching game’. Pages 86–100 in Golden Shells and Elegant Games of Japan, edited by Wayne Crothers. National Gallery of Victoria: Melbourne. ISBN: 978-1-925432-77-0.

McCullough, William H. and Helen Craig McCullough (). A Tale of Flowering Fortunes: Annals of Japanese Aristocratic Life in the Heian Period. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA.

Ito, Setsuko (). ‘The Muse in Competition: Uta-awase Through The Ages’. Monumenta Nipponica vol. 37 (2): pages 201–222. Sophia University.

Royston, Clifton W. (). ‘Utaawase Judgments as Poetry Criticism’. The Journal of Asian Studies vol. 34 (1): pages 99–108.

Sakomura, Tomoko (). ‘Japanese Games of Memory, Matching, and Identification’. Pages 252–271 in Asian Games: The Art of Contest, edited by Colin Mackenzie and Irving Finkel. Asia Society. ISBN: 0-87848-099-4.

高橋, 浩徳 [Takahashi Hironori] (). ‘貝覆い’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. Boardwalk Community.

McKinney, Meredith (). Essays in Idleness and Hōjōki. Penguin Group: London, UK. ISBN: 978-0-14-195787-6.

Yamazaki, Tatsufumi [山崎 達文] (). ‘A golden opportunity: reviving the lost art of kai-awase and kai-oke production’. Pages 2–22 in Golden Shells and Elegant Games of Japan, edited by Wayne Crothers. National Gallery of Victoria: Melbourne. ISBN: 978-1-925432-77-0.

Saunders, Rachel (). ‘Birds, Flowers, and Botany in Sakai Hōitsu’s Pure Land Garden’. Pages 101–172 in Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection, Rachel Saunders and Yukio Lippit. Harvard Art Museums. ISBN: 978-0-300-25089-3.

Debouck, Pieterjan (). Satire within kibyōshi in eighteenth-century Edo: a translation and analysis of Santō Kyōden’s ‘Tama Migaku Aoto ga Zeni’. Master’s dissertation, University of Ghent: Ghent, Belgium.

van Overmeer Fisscher, J. F. (). Bijdrage tot de kennis van het Japansche rijk [text in Dutch]. J. Müller & Comp.: Amsterdam.

江橋, 崇 [Ebashi Takashi] (). 花札 [text in Japanese]. 法政大学出版局: Tōkyō, Japan.

江橋, 崇 [Ebashi Takashi] (). ‘花札の公然の販売‥‥「上方屋」の挑戦’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. Japan Playing Card Museum.

Takahashi, Kōsuke (). ‘Capital punishment: Japan’s yakuza vie for control of Tokyo’. Jane’s Intelligence Review, .

大石天狗堂 [Ōishi Tengudō] (). ‘大石天狗堂口伝 第四章’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. 大石天狗堂 [Ōishi Tengudō].

Keene, Donald (). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His world, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 0-231-12340-X.

Takeuchi, Rio (). ‘Invention of the West in Japan’. Pages 23–42 in The East and the Idea of Europe, edited by Katalin Miklóssy and Pekka Korhonen. Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. ISBN: 978-1-4438-2531-3.

Suematsu, Kenchō (). A Fantasy of Far Japan: Or, Summer Dream Dialogues. Archibald Constable & Co.: London, UK.

前田, 喜兵衛 (). 骨牌勝利法 : 文明遊具 一名・まける事しらず [text in Japanese]. 上方かるた商店: Tokyo, Japan.

江橋, 崇 [Ebashi Takashi] (). ‘花札図柄の「煙草カード」’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. Japan Playing Card Museum.

Wintle, Simon (). ‘National Card Co.’ [archived]. On the website The World of Playing Cards (accessed ).

Iwata, Nishizawa (). Japan in the Taisho Era.

Durdern, Robert F. (). ‘Tar Heel Tobacconist in Tokyo, 1899–1904’. The North Carolina Historical Review vol. 50 (4): pages 347–363. North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

Paumgarten, Nick (). ‘Master of Play’. The New Yorker, .

Shaw, Gina (). What Is Nintendo?. Penguin Workshop. ISBN: 0-593-09379-8.

McAlpine, Kenneth B. (). Bits and Pieces: A History of Chiptunes. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 978-0-19-049609-8.

Nichols, Randy (). Nintendo: Playing with Power. Taylor & Francis. ISBN: 978-1-003-81682-9.

Firestone, Mary (). Nintendo: The Company and its Founders. ABDO. ISBN: 978-1-61714-809-5.

Brown, Brian “Box” (). Tetris: The Games People Play. First Second. ISBN: 978-1-250-14589-5.

Thomas, Rachael L. (). Nintendo Innovator: Hiroshi Yamauchi. ABDO. ISBN: 978-1-5321-5996-1.

Green, Sara (). Nintendo. Bellwether Media. ISBN: 978-1-68103-175-0.

Kohler, Chris (). Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. Courier Dover. ISBN: 978-0-486-80149-0.

Sloan, Daniel (). Playing to Wiin: Nintendo and the Video Game Industry’s Greatest Comeback. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 978-0-470-82693-5.

Sutherland, Adam (). The Story of Nintendo. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN: 978-1-4488-7096-7.

Chaplin, Heather and Aaron Ruby (). Smartbomb: The Quest for Art, Entertainment, and Big Bucks in the Videogame Revolution. Hachette UK. ISBN: 978-1-56512-835-4.

Santos, Wayne (). ‘The 100-Year Chronicles of Nintendo’. GameAxis Unwired (16), : pages 8–12.

Percy, Sally (). The Disruptors: How 15 Successful Businesses Defied the Norm. Kogan Page Publishers. ISBN: 978-1-3986-1649-3.

Houze, Rebecca (). New Mythologies in Design and Culture: Reading Signs and Symbols in the Visual Landscape. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN: 978-1-4742-7771-6.

Sheff, David (). Game Over, Press Start to Continue: How Nintendo Conquered the World. GamePress: Wilton, CT, USA. ISBN: 0-9669617-0-6.

Anonymous (). ‘Grants to the Kuge Nobles’. The Japan Weekly Mail vol. 21 (12), . Jappan Mēru Shinbunsha: Yokohama, Japan.

Salter, Rebecca (). Popular Japanese Prints. University of Hawaiʻi Press: Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. ISBN: 978-0-8248-3083-0.

江橋, 崇 [Ebashi Takashi] (). ‘骨牌税法の内容’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. Japan Playing Card Museum.

夏, 鲤衣荷 [Xià Lǐyīhé] (). ‘在卖游戏之前,任天堂还上演过一出豪门宫斗’ [text in Chinese] [archived].

内閣府 (). ‘娯楽に関する世論調査’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. 内閣府大臣官房政府広報室: Tokyo, Japan.

NapoleonCat (). ‘Instagram Users in Japan, April 2021’ [archived]. NapoleonCat.

NapoleonCat (). ‘Instagram Users in Korea, April 2021’ [archived]. NapoleonCat.

Shirane, Haruo (). Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons. Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-0-231-52652-4.

McCollough, Helen (). Kokin Wakashū: The First Imperial Anthology of Japanese Poetry. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA. ISBN: 0-8047-1258-1.

Fairbairn, John (). ‘The Poems of the Echigobana’. Journal of the International Playing-Card Society vol. 14 (4), : pages 97–102.

Satow, Ernest Mason and A. G. S. Hawes (). A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan. Kelly & Co.: Yokohama, Japan.

Yuasa, Nobuyuki (). The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Penguin Books: Middlesex, England, UK. ISBN: 0-14-044185-9.

Bowers, Faubion (). The Classic Tradition of Haiku. Dover Publications: Mineola, New York, USA. ISBN: 0-486-29274-6.

McCollough, Helen (). Heike Monogatari. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA. ISBN: 978-0-8047-1803-5.

McAuley, Thomas (). ‘KKS III: 135’ [archived]. On the website Waka Poetry (accessed ).

Gorges, Florent (). ‘In The Chair: Satoru Okada’. Retro Gamer UK (163): pages 92–97. Edited by Darran Jones. Future Publishing.

Palmer, H. Spencer (). ‘Hana-Awase’. Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan vol. 19, : pages 545–564.

McCollough, Helen (). Tales of Ise: Lyrical Episodes from Tenth-Century Japan. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA. ISBN: 0-8047-0653-0.

Du Cane, Ella and Florence Du Cane (). The Flowers And Gardens Of Japan. Adam & Charles Black: London.

Gill, Robin D. (). ‘The Peon and the Peony’ [archived]. Simply Haiku vol. 3 (2).

Shimada, Hidemasa (). ‘森川許六『風俗文選』より、「百花ノ譜」’ [archived]. On the website 跡見群芳譜 (accessed ).

Ueda, Makoto (). The Path of Flowering Thorn: The Life and Poetry of Yosa Buson. Stanford University Press: Stanford, California. ISBN: 0-8047-3042-3.

Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai (). The Manyōshū. Columbia University Press: New York, USA. ISBN: 0-231-02818-0.

Dower, John (). The Elements of Japanese Design. Weatherhill: Boston, MA, USA. ISBN: 978-0-8348-0229-2.

Arnold, Edwin (). Wandering Words. Longmans, Green, and Co.: London & New York.

Lehner, Ernst and Johanna Lehner (). Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants, and Trees. Tudor Publishing Company: New York, USA. ISBN: 978-0-8148-0320-2.

McAuley, Thomas (). ‘SKKS IV: 442’ [archived]. On the website Waka Poetry (accessed ).

Atkins, Paul (). ‘Chigo in the Medieval Japanese Imagination’. The Journal of Asian Studies vol. 67 (3): pages 947–970.

Greve, Gabi (). ‘Ricewine (sake)’ [archived]. On the website World Kigo Database (accessed ).

Clement, Ernest W. (). The Japanese Floral Calendar. The Open Court Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA.

Huey, Robert (). The Making of Shinkokinshū. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA. ISBN: 978-0-674-00853-3.

Ōishi Tengudō (). ‘花札の謎シリーズ!11月札『柳に小野道風(おののとうふう)』’ [archived]. Ōishi Tengudō.

江橋, 崇 [Ebashi Takashi] (). ‘後世の花札図柄との異同’ [text in Japanese] [archived]. Japan Playing Card Museum.

Volker, T. (). The Animal in Far Eastern Art. E. J. Brill: Leiden, Netherlands. ISBN: 90-04-04295-4.

van Rensselaer, Mrs. John King (). The Devil’s Picture-Books. Dodd, Mead, and Company: New York, USA.

村井, 省三 [Murai Shōzō] (). ‘明治の花札’ [text in Japanese]. 別冊太陽 (9): pages 160–4.