Nine Men’s Morris

Last updated: .

Nine Men’s Morris is an ancient mill game dating at least from Roman times. It is the most prominent of all the mill games, played all around the world, but particularly in central European countries. Other variations of the game — such as Shax or Morabaraba — are also played in several African countries.

In addition to being a game, the board itself was used as some kind of talisman or symbol; The Merels Board Enigma (p. 330) collects nearly a thousand examples of inscribed mill boards from around the world. Many of these are in vertical positions on walls where they could not possibly have been used for games, and their purpose is at the moment not well understood.

A large-format Nine Men’s Morris game being played at a festival in Hungary.

Play

Nine Men’s Morris is played on the large mill board.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The game (as most mill games) is split into two phases. During the first (placement) phase, the players take turns placing a single piece at a time onto one of the vacant points on the board. Once all the pieces have been placed, the movement phase begins. In this part of the game, players take turns moving a single piece along a line to another vacant point. Once a player is reduced to three pieces, their pieces can ‘fly’ and move to any empty point on the board.

Throughout the game, each time a player forms a mill they remove any piece of their opponent’s that is not part of a mill. If all their opponent’s pieces are in mills, no piece may be removed.

During the movement phase, it is possible to form two mills simultaneously. In this case the player may remove two of the opponent’s pieces from the board.

A player loses the game when they are reduced to fewer than three pieces, or if they are unable to make a valid move on their turn.

When played on a board with diagonals, mills are not usually permitted to be made on the diagonal lines. However, this varies according to location and time.

History

A Nine Men’s Morris board of unknown age in the Roman Agora, Athens.

© 2014 George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

A board carved on the capital of the Athenian trophy (or tropaion, τρόπαιον) from Marathon, which was constructed some time after 490 BCE but destroyed at a later date. An image of the board carved on the decapitated capital in situ can be seen in Vanderpool (1966, plate 32).

© 2012 Dan Diffendale, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The game dates from at least the late Roman Empire or Byzantine period, and at the moment we do not have solid evidence for an earlier date.C (p. 3) Earlier dates have often been proposed based upon the existence of boards carved on ancient monuments such as the RamesseumD (p. 144) and the Mortuary Temple of Seti I at Qurna,E (p. 644) but these are not able to be dated definitively—the monument only provides an earliest possible date.This is also discussed at length in Schädler (2021).

The game became popular throughout Europe: a double-sided game board with a Nine Men’s Morris layout on one side was found as part of the Gokstad Viking ship burial (c. 900) which was discovered in Norway.G (pp. 44, 99) Another boat burial (the “Årby boat”) from around the same time also included a Morris game.H (p. 441)

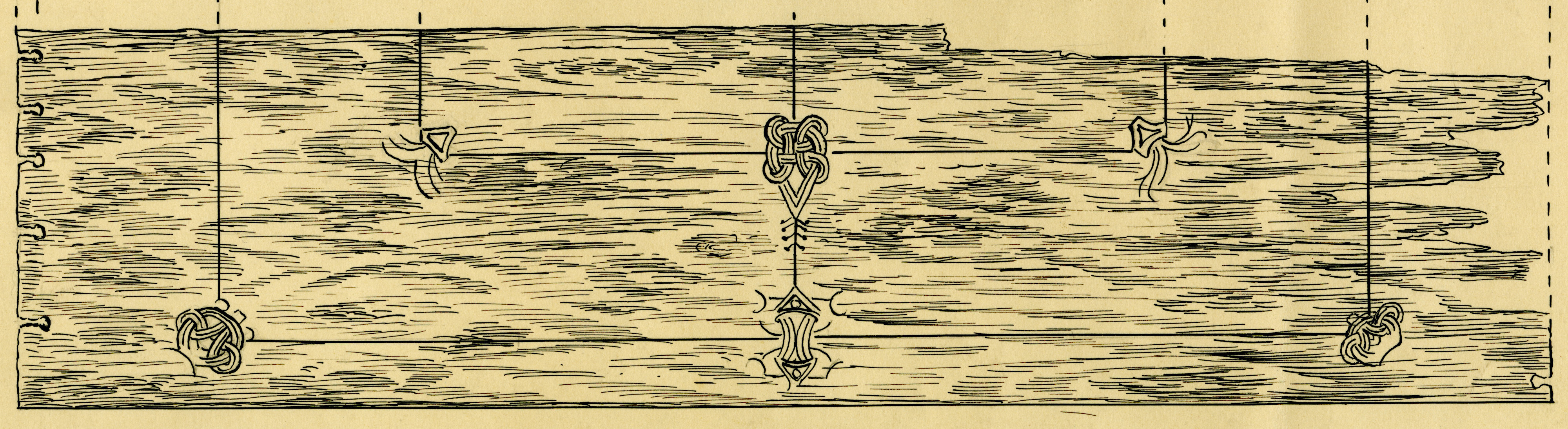

Sketch and photograph of the board from the Gokstad ship.

One of the earliest written references to the game is in the 10th century Kitāb al-Aghānī (كتاب الأغاني, ‘book of songs’), a large collection of poems and stories assembled by ʾAbū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (أبو الفرج الأصفهاني, 897–967). One story describes a club from the time of the poet al-Aḥwaṣ (الأحوص, 660–724), along with the board games it held for the use of its members. According to the book, they could play shiṭranj (شطرنج, chess), nard (نرد), or — most importantly here — qirq (قرق, morris).I (p. 481) The derivation of the name qirq (قِرْقٌ) is uncertain,It may also be related to the Geʽez word ቀርቂስJ (pp. 424–5) (qarqis), referring to various games,K (p. 443) or the (Ottoman) Turkish قرق/kırk ‘forty (=many)’.L (p. 989) but it is apparently not originally an Arabic word.M (p. 37)The Imam ʾAbū al-Qāsim al-Rāfiʿī al-Qazwīnī (أبو القاسم الرافعي القزويني, 1160–1226) would later describe qirq as the “chess of the Maghrebis”.I (p. 381) Similarly, Shax is sometimes referred to as “Somali chess”.

Later, Faīrūzābādī (of whom, more below) would identify qirq with suddar (سُدَّر), apparently derived from the Persian se darre (سِهْدَرَهْ), meaning ‘three valleys’.N (pp. 207–9) However, in other dictionaries suddar is identified with other games such as aṭ-ṭabanu (الطَّبَنُ), which is known as a different game today (modern name aṭ-ṭāb الطاب).O It is probable that in the past, names of games were more fluid, and often referred to families of games. Even in modern Arabic the name ʾidrīs (ادريس) is used to refer to mill games, but also refers to loosely related games such as Quantik. With that said, a Persian origin for the game does seem likely, given the number of ways that suddar is rendered in Arabic dictionaries.Other versions of the name are given as سِهْ بَرَهٌ (sih barahun), سِيدَرَهِ (sīdarahi), سِدْرَه (sidrah), سَذْ مَرَهْ (saḏ marah), or سِدْ مَزْه (sid mazh).O

From the Arabic-speaking world the game entered Spain, where al-qirq became alquerque, which has remained the Spanish name for this family of games until the present day.

In France the game was in the past called marelles (from which we get the English ‘merels’), probably deriving from a word meaning “small stone” or “token”.The marelles name currently refers to hopscotch, due to the stones tossed upon the diagram.

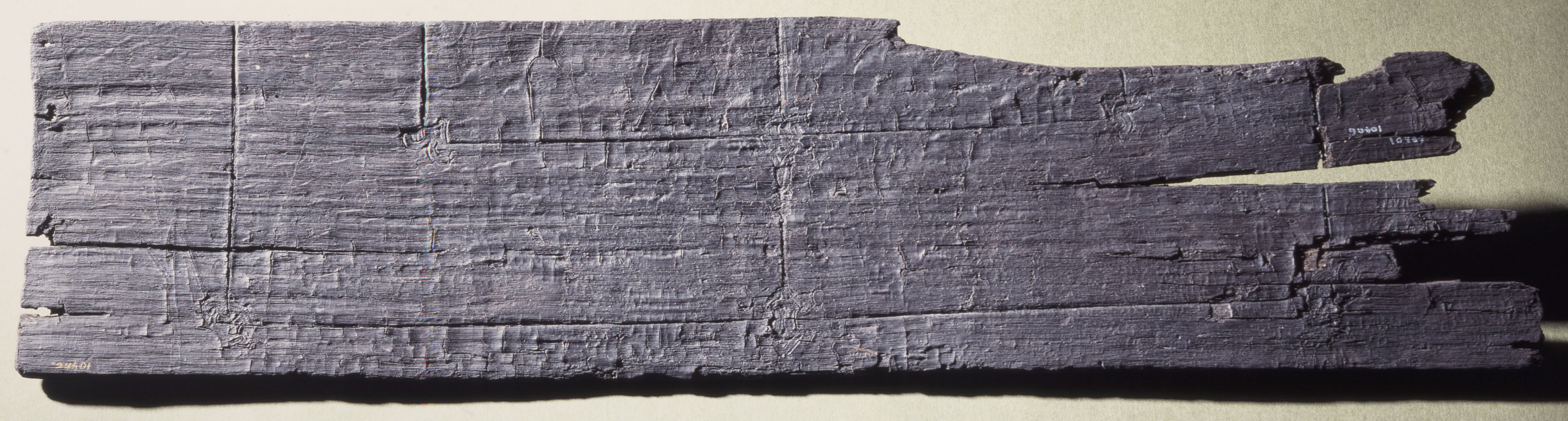

Text of the French Templar rule from an early 14th-century manuscript edition (with quoted passage highlighted).

In the early 12th century, the game was mentioned in the French Rule of the Templar order (probably written between 1139 and 1147 CEP (p. 12)), as the only board game allowed to be played by Templar brothers. It is possible that the order picked up the game through their contact with the Arabic-speaking world:Indeed, a board has been found inscribed upon a stone in Château Pèrelin, a fortress constructed by the Templars in what is now Israel — although it could have been placed there any time since the fortress was built.Q (p. 60)

Et sachies que a nul autre jeu frere dou Temple ne doit joer, fors qu’a marelles as queles chascun puet juer se il veaut por desduit sans metre gajeures. As eschas ni a tables nul frere dou Temple ne doit juer, ne as eschaçons.R (p. 185)

And let it be known that a brother of the Temple should play no other game except marelles, which each may play if he wishes, for pleasure without placing wagers. No brother should play chess, backgammon, or eschaçons [an unknown game].P (p. 90)

It is unclear why mill games were permitted by the Templars, but, reading the rest of the passage (not quoted above), the intent of the Rule seems to be to prevent playing games for money — bets were allowed to be placed on games, but only with worthless items such as wooden tent pegs. Viewed in this light, perhaps mill games were considered less susceptible to gambling, and therefore permissible.

In 1283 it appeared in the Castilian king Alfonso X’s Libro de los Juegos (Book of Games), where in addition to the standard game, rules for playing with dice are given (see below).

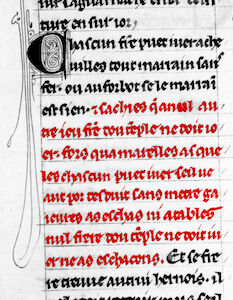

From Alfonso’s Book of Games.

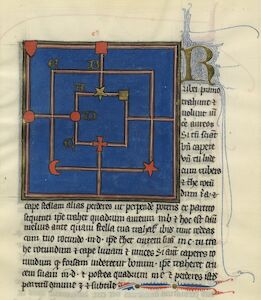

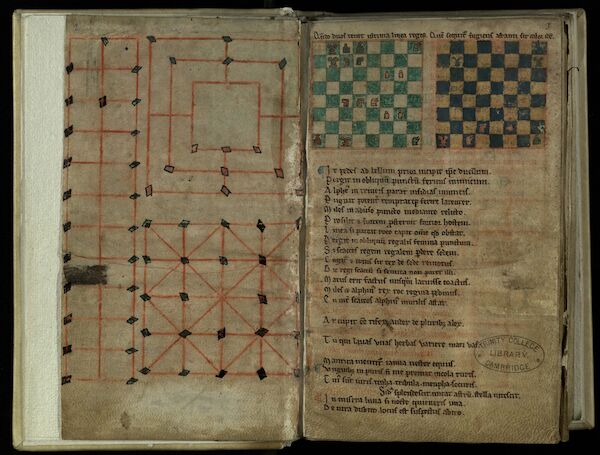

The first problem in one of the Bonus Socius manuscripts written in Picardy (MS Latin 10286). The different shapes of the pieces in the diagram are used to identify particular pieces in the accompanying text.

In the same century the Bonus Socius series of manuscripts contained problems for the game, alongside other problems for chess and various table games.S (p. 619) Chess historian H. J. R. Murray describes the problems as being of very high quality, and that in fact “they leave a more favourable impression of the ingenuity of the mediaeval composer than is the case with the problems of chess or tables.”S (p. 703)

A 13th-century English manuscript (MS O.2.45) from Cerne Abbey shows a Nine Men’s Morris board alongside an Alquerque board and another unidentified board (possibly Daldøs).

By examining depictions of the game in artwork, we can understand the attitude towards the game at the time the image was produced. In the manuscript image below (c. 1340), nobles of opposite sex face each other across a game board. Evidently the game was considered worthy of being played by the nobility, and suitable for men and women to play together:

A woman and a man playing Nine Men’s Morris together, miniature from a copy of the Romance of Alexander (produced 1338–44).

© 2015 Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, 🅭🅯🄏: SC=2464

The previous scene is in stark contrast to this German woodcut by Hans Weiditz from Trostspiegel in Glück und Unglück (p. 24) — a version of Petrarch’s De remediis utriusquefortunae published some 200 years later in 1572. In this image we can see Chess being played by nobles and Backgammon by ordinary men, but Nine Men’s Morris is evidently only suitable to be played by monkeys:

2012 Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliothek, 🅮

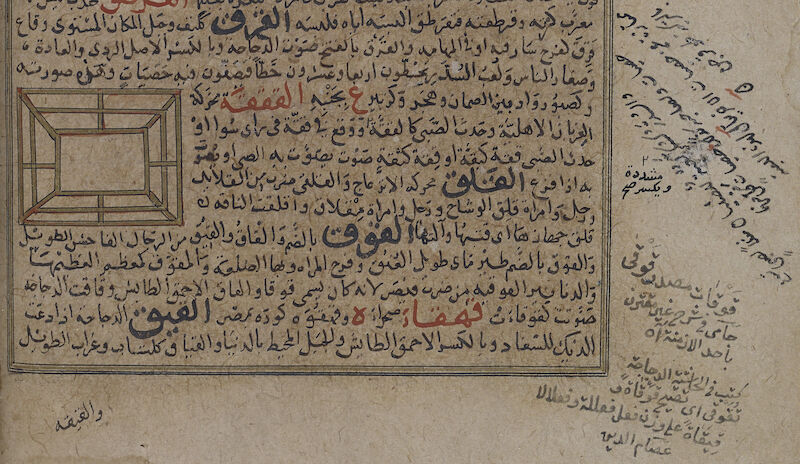

The board with diagonals seems to appear first in Arabic sources;M (p. 43) it is shown — as the only drawing — in the famous al-Qamūs al-Muḥīṭ dictionary (القاموس المحيط, ‘The Surrounding Ocean’) of Fairūzābādī (فیروزآبادی, 1329–1414), published at the start of the 15th century.U

In China the game is mentioned by the Ming Dynasty author Xiè Zhàozhè (谢肇淛, 1567–1624 CE) in his Five Assorted Offerings (五杂组),V and game-boards (almost entirely of the ‘diagonals’ type) have been found in China, starting from boards dated to the the 8–9th centuries in the Uighur Khaganate in what is now Mongolia, to the Balhae kingdom in the 9–10th centuries, and eventually spreading throughout the rest of China through the Liao/Song, then Jin and Yuan dynasties (10–14th centuries). It seems probable that the game reached China through the Silk Roads from the Middle East.V

The entry for “القَرْقُ” in the Qamūs. The game is here identified with suddar.

© University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, 🅭🅯

In later English history the game developed an association with rusticity, often mentioned as a game played by shepherds. In such guise it famously appears — albeit relocated in time and place to a fictional ancient Athens — in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (c. 1595), where, thanks to a feud between Titania and Oberon (queen and king of the fairies), the natural state of the countryside is upended, and:

The ox hath therefore stretch’d his yoke in vain,

The ploughman lost his sweat, and the green corn

Hath rotted ere his youth attain’d a beard.

The fold stands empty in the drowned field,

And crows are fatted with the murrion flock;

The nine men’s morris is filled up with mud,

And the quaint mazes in the wanton green

For lack of tread are undistinguishable.

The game can be seen in English history through its appearance in visitation records; one instance from the parish of Bitteswell records that in 1634 a certain Robert Lord the Younger was “admonished and dismissed” for “plaieing at nine men’s morrice in the Churchyard on Sundaie”.W (p. 497)

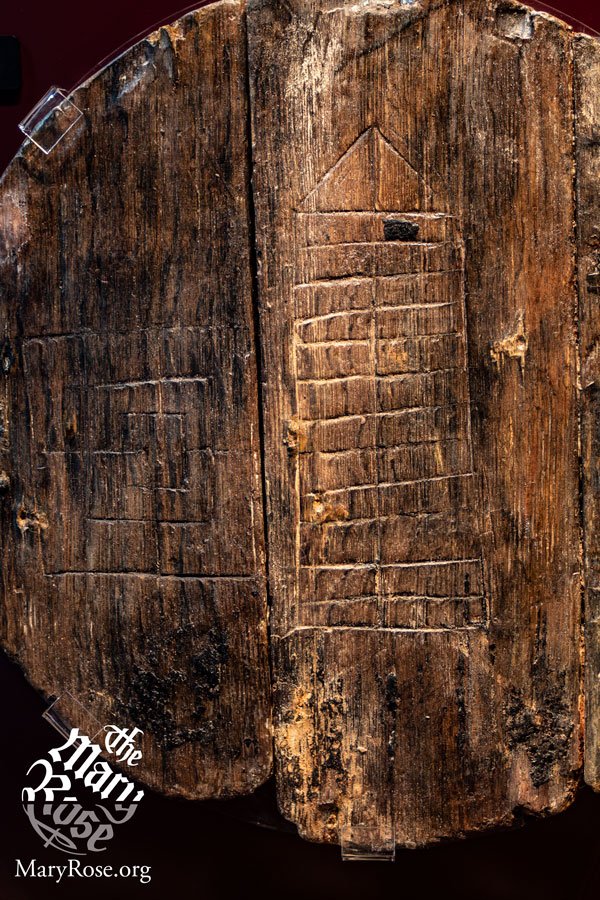

A Nine Men’s Morris board alongside what seems to be a Daldøs board, on a barrel-end from the wreck of the English warship ‘Mary Rose’ (1545).

© The Mary Rose Museum, used with permission

Detail from the 16th-century tapestry Suite des Nobles Pastorales.

In colonial America, the game began to be played with twelve pieces (exclusively on the board with diagonals) and thus became the standard American form, known as Twelve Men’s Morris.Rules for a game called alquerque de doze, sometimes translated as Twelve Men’s Morris, are given in Alfonso X’s Book of Games, but it describes a game of a different form.

Nomenclature

Other English names for the game have included:

Blind Men’s Morris (LeicestershireX (p. 130))

Buttons (played on a slate with buttons in 1890s New ZealandY (p. 151))

Figmill (in Clarence, New York, USA)Z (This name derives from an American manufacturer of equipment, but originally might derive from the Swiss term «Figgi und Müli».)

Morris (CornwallX (p. 130))

Marl (WiltshireX (p. 130))

Maurice or Morrice (NorfolkX (p. 130))

Mill (DevonX (p. 130))

Meg Merry-legs (LincolnshireX (p. 130))

Merils (Essex X (p. 130)), MerrilsAB (p. 414), or MerrillsAA (p. 173)

MerellesAB (p. 415)AA (p. 90)X (p. 130) or Merell(s)AB (p. 416)

Merry Hole (NorthamptonshireX (p. 130))

Merry Peg (OxfordshireX (p. 130))

MorelsX (p. 130)

Murrells (CambridgeshireX (p. 130))

NinepennyX (p. 130) or Ninepenny Morris (in Gloucestershire – but played with 12 men)AB (p. 416)

Nine Holes (North of EnglandX (p. 130))

Nine Men’s WelcomeAC (p. 103)

Nine Peg O Merryal (North LincolnshireX (p. 130))

(Nine) Peg Morris (by John Clare, a rustic English poet)AB (p. 416)

Peg Meryll (played in Hargrave with 11 men, and ‘flying’ at 5 menX (p. 133)) or MerrilpegAB (p. 416)

Study, in the north of EnglandAD

In other languages it has been called:

Bangla: ন গুটি (na guṭi) ‘nine beads’, or পাইত(-পাইত) (pāit(-pāit)) ‘get(-ting)’AE

Chinese:

An old name is 馬城 (Mandarin: mǎ chéng) ‘horse walls’V (4)

More modern names include: 成三棋 (Mandarin: chéng sān qí) ‘achieving three game’,V (4) or simply 三棋 (Mandarin: sān qí) ‘three game’AF (102)

連棋 (Mandarin: lián qí) ‘lining-up game’V (4)

連環馬棋 (Mandarin: lián huán mǎ qí) ‘interlinked horses“Horse” is the usual term for a game piece. game’V (4)

捉三 (Cantonese: zuk¹ saam¹; Mandarin: zhuō sān) ‘catching three’AD

直棋 (Mandarin: zhí qí) ‘line game’V (4)

吉日格 jí rì gé,V (4) apparently derived from the Mongolian name for this class of game, жирэг (ᠵᠢᠷᠡᠭ?)AG (39–40)

In Teochew it can be called 直直 (dig⁸ dig⁸) ‘straight line’,AH and there was a Teochew proverb that “[Chinese] chess is for immortals; straight-line is for beggars” (仙棋乞食直 siêng¹ gi⁵ keg⁴ ziah⁸ dig⁸).AHMuch thanks to Brandon Seah for helping to figure this transliteration out.

French: le jeu du moulin ‘the mill game’

Greek: τὸ τριόδι ‘trio’AI (p. 295), or τριώδιον ‘triodium’.N (p. 205)

German: names are based on the number nine, e.g. Neunstein ‘nine stone’, Neunten Stein ‘ninth stone’, Neunemahl ‘nine flour’; or on the mill, e.g. Mühlespiel ‘mill game’. Research by Jonas Richter indicates that the ‘nine’ names are the older form.AJ In 1575 Johann Fischart included it in his version of Gargantua as Fickmül.See the Gargantua article for more about Fischart’s list.

Gujarati: નવ કાકરી (nav kākarī) ‘nine pieces’

Hindi: नवकंकरी (navakaṅkarī),AK or नव गोटी (nav gōṭī), both meaning ‘nine pieces’

Kannada: ನವಕಂಕರಿ (navakaṅkari) ‘nine pieces’, ಒಂಬತ್ತು ಕಾಯಿಯ ಆಟ (ombattu kāyiya āṭa) ‘game of nine nuts (=pieces)’, or generically ಸಾಲು (ಮಣೆ) ಆಟ (sālu (maṇe) āṭa) ‘row (board) game’

Korean: 곤질(고누) (gonjil(-gonu))Given as kon-tjil in older books.AF (p. 102)

Ottoman Turkish: طقوز طاش (dokuz taş) ‘nine stone’, or دقورجین (dokurġin) [something to do with nine?]N (p. 206)

Swiss: Nüünischtei.AM

Telugu: దాడి (dāḍi) ‘attack’

Urdu: نو گوٹی (nau guṭī) ‘nine pieces’AN (p. 145)

A jeu du moulin in the south-west wall of the Château du Moulin (Loir-et-Cher, France). Built between 1480–1501, this is a punny reference to the name of the original owner, Philippe du Moulin. There is another Three Men’s Morris board on the eastern wall, and the nearby Château de Gien has a similar motif.A (p. 103)

© 2016 Ken Broadhurst, used with permission

Analysis

With perfect play, the game is a draw.AOAP Interestingly, it is possible for the starting player to make a losing move as early as their third turn.AO (112)

Variants

Alternate boards

The standard rules can be adapted to play on many different boards. As in standard Nine Men’s Morris, mills must always be in a straight line and may not turn corners.

Babbage also apparently experimented with differently-shaped boards, in both triangular and pentagonal shapes,AQ but I have not yet been able to see the manuscript in question.

Alternate boards of German origin:AR (p. 58) a ‘sun-mill’ (played with 12 pieces each), and two boards constructed from nested pentagons. The first pentagonal board is played with 11 pieces each, the second is designed to be played by two or more players: for two players use 12 pieces; for three, 8; for four, 6; and for five, 5.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Two variations of a ‘cube’ board by David Parlett.AS (p. 122) On the coloured board, a mill may not cross between differently-coloured regions, and the middle point may only be taken to complete a mill or prevent completion of a mill on the next turn.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

The Möbius board (invented by Ingo Althöfer), another pentagonal board (without joined corners), and a hexagonal board.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Twelve Men’s Morris

This is played with twelve pieces per player, on a board that has diagonals.AT (p. 7)M (p. 48) In all other respects, the game is the same.

A Twelve Men’s Morris game being played.

© Shutterstock.com/Delpixel : 235028281

Nomenclature

In other countries or languages Twelve Men’s Morris has been known as:

Bengali: বারো গুটি (পাইত পাইত) (bārō-guṭi (pāit-pāit)) ‘twelve bead [unsure]’.AN (p. 145)

Sri Lanka (Sinhala): නෙරෙංචි or නෙරිංචි (nereṁciAlso transcribed as Nerenchi or Niranchy. or neriṁci), possibly named after a plant that has very thorny seeds.AT (p. 16)AU (p. 34)E (p. 577)

Urdu: بارہ گوٹی (bārā guṭī) ‘twelve pieces’.

With Dice

A game being played with dice, from Alfonso X’s Book of Games.

Alfonso X’s book of games describes a variant played with dice.AV While it is unclear from the manuscript what the exact rules are, Ulrich Schädler offers the following interpretation:AWThis interpretation disagrees with previous interpretations given in A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess and Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations; see the article for full details.

During the placement phase, no mills may be made.

During the movement phase, each player rolls three dice before moving a piece. If they roll any of the special rolls

,

,

, or

, they may ‘fly’ a piece from anywhere on the board to complete a mill (or two mills). For any other result, the player moves as normal.

Lasker Morris

This variant was developed by Emanuel Lasker, who was World Chess Champion from 1894 to 1921. It unifies the two phases of the game into one.

Play is as in the standard game, except that each player has 10 pieces instead of 9, and on a player’s turn they may either place a new piece or move a piece that is already on the board.

See also

Other general references include The Oxford History of Board Games, Math Games & Activities from Around the World (p. 12), Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (vol. 1, p. 93), A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess (§3.5.4, p. 43), Goddard (1901), Notes and Queries (pp. 28, 89–90, 173, 333), and Played at the Pub (p. 150).

References

Uberti, Marisa (). The Merels Board Enigma. Marisa Uberti. ISBN: 978-88-6755-413-3.

Vanderpool, Eugene (). ‘A Monument to the Battle of Marathon’. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens vol. 35 (2): pages 93–106.

Schädler, Ulrich (). ‘Games, Greek and Roman’. In Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA.

Crist, Walter, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi, and Alex de Voogt (). Ancient Egyptians at Play. Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK. ISBN: 978-1-4742-2119-1.

Parker, Henry (). Ancient Ceylon. Luzac & Co.: London, UK.

Schädler, Ulrich (). ‘Some misconceptions about Ancient Roman Games’. Board Game Studies vol. 15 (1), : pages 79–97. De Gruyter Open. doi:10.2478/bgs-2021-0004.

Nicolaysen, N. (). The Viking-Ship from Gokstad. Alb. Cammermeyer: Oslo, Norway.

Hall, Mark A. (). ‘Board Games in Boat Burials: Play in the Performance of Migration and Viking Age Mortuary Practice’. European Journal of Archaeology vol. 19 (3): pages 439–455. doi:10.1080/14619571.2016.1175774.

Rosenthal, Franz (). ‘Gambling in Islam’. Pages 338–516 in Man versus Society in Medieval Islam, edited by Dimitri Gutas; Brill Classics in Islam volume 7. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands. ISBN: 978-90-04-27089-3. doi:10.1163/9789004270893_005.

Dillmann, Augusti [Christian Friedrich August Dillmann] (). Lexicon Linguae Aethiopicae [text in Latin] volume 1: ‘ሀ፡ — ነኀረ፡’. T. O. Weigel: Leipzig, Germany.

Leslau, Wolf (). Comparative Dictionary of Geʽez. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden. ISBN: 3-447-02592-1.

Mallouf, Nassif (). Dictionnaire Turc-Français [text in French] volume 2: ‘ع–ى’. Maisonneuve et Cie: Paris.

Murray, H. J. R. (). A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, UK. ISBN: 0-19-827401-7.

Hyde, Thomas (). De Ludis Orientalibus Libri Duo [Two Books On Oriental Games; text in Latin] volume 2: ‘Historia Nerdiludii [History of the Nerd-game]’. E Theatro Sheldoniano: Oxford, UK.

Hawramani, Ikram (). ‘Arabic–English Lexicon by Edward William Lane (d. 1876): طبن’ [archived]. On the website The Arabic Lexicon (accessed ).

Upton–Ward, J. M. (). The Rule of the Templars. The Boydell Press: Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK. ISBN: 0-85115-315-1.

Johns, C. N. (). ‘Excavations at Pilgrims’ Castle, ʿAtlit (1932–3); Stables at the South-West of the Suburb’. The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine vol. 5: pages 31–61.

De Curzon, Henri (). La Règle Du Temple [text in French]. Librairie Renouard: Paris, France.

Murray, H. J. R. (). A History of Chess. Skyhorse Publishing: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-1-62087-062-4. First published in 1913.

Petrarca, Francesco (). Trostspiegel in Glück und Unglück [text in German]. Frankfurt.

فيروزآبادى, محمد بن يعقوب [Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb al-Fīrūzābādī] (). القاموس المحيط [The Surrounding Ocean; text in Arabic].

Wu, Song and Pauline Sebillaud (). ‘Research on the merels game in medieval China’. Asian Archaeology vol. 4 (1), : pages 41–52. doi:10.1007/s41826-020-00037-z.

Anonymous (). ‘The Metropolitical Visitation of Archdeacon Laud’. Associated Architectural Societies Reports and Papers vol. 29: pages 477–534. Edited by A. Percival Moore.

Baker, R. S. (). ‘Peg Meryll’. Associated Architectural Societies’ Reports & Papers vol. 11 (1): pages 127–134.

Sutton–Smith, Brian (). ‘The Games of New Zealand Children’. Pages 5–257 in The Folk-Games of Children. The American Folklore Society. ISBN: 0-292-72405-5.

Heist, William W. (). ‘Figmill’. The Journal of American Folklore vol. 64 (253): pages 303–306. American Folklore Society.

John C. Francis (). Notes and Queries volume 12 (Series 8). John C. Francis: London, England, UK.

Gomme, Alice Bertha (). The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland volume 1: ‘Traditional Games’. David Nutt: London, UK.

Finn, Timothy (). Pub Games of England (2nd edition). The Oleander Press: Cambridge, England, UK. ISBN: 0-900891-66-1.

Lister, Alfred (). ‘Tipcat, and Other Chinese Games’. Notes and Queries on China and Japan vol. 4: pages 125–128.

Tarafder, Shabbir Ahmmed (). ‘লৌকিক খেলা - পাইত | Folk game - pait’. On the website YouTube.

Culin, Stewart (). Korean Games with notes on the corresponding games of China and Japan. University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA. ark:/13960/t1pg2586d.

Kabzińska-Stawarz, Iwona (). Games of Mongolian Shepherds; The Library of Polish Ethnography number 45. Institute of the History of Material Culture, Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland. ISBN: 83-85463-02-X.

Newell, W. H. (). ‘A Few Asiatic Board Games Other than Chess’. Man vol. 59, : pages 29–30.

Abbott, George Frederick (). Macedonian Folklore. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Richter, Jonas (). ‘German Names for Merels’. Board Game Studies vol. 17 (1), : pages 167–204. De Gruyter Open. doi:10.2478/bgs-2023-0005.

Raghavan, Raamesh Gowri (). Ancient Indian Board Games. Centre for Extra-Mural Studies, INSTUCEN Trust: Mumbai.

SRF Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (). ‘Mundart-Lexikon’ [text in Swiss German]. SRF Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen.

Das-Gupta, Hem Chandra (). ‘A Few Types of Sedentary Games prevalent in the Punjab’. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal vol. 22: pages 143–148.

Gasser, Ralph (). ‘Solving Nine Men’s Morris’. Pages 101–113 in Games of No Chance, edited by Richard J. Nowakowski; MSRI Publications volume 29. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN: 978-0-521-64652-9.

Gévay, Gábor E. and Gábor Danner (). ‘Calculating Ultrastrong and Extended Solutions for Nine Men’s Morris, Morabaraba, and Lasker Morris’. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games vol. 8 (3): pages 256–267.

Singmaster, David (). ‘Sources in recreational mathematics’ [archived].

Bücken, Hajo and Dirk Hanneforth (). Klassische Spiele ganz neu [text in German]. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag: Germany. ISBN: 978-3-499-18901-2.

Parlett, David (). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, UK. ISBN: 978-0-19-212998-7.

Zaslavsky, Claudia (). Math Games & Activities from Around the World. Chicago Review Press: Chicago, IL, USA. ISBN: 1-55652-287-8.

Ludovici, Leopold (). ‘The Sports and Games of the Singhalese’. The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland vol. 5 (18): pages 17–41. Ceylon Times Press: Colombo, Sri Lanka. hdl:2027/mdp.39015020463454&view=1up&seq=41.

Alfonso X (). Libro de açedrex, dados e tablas. Alfonso X: Toledo, Spain.

Schädler, Ulrich (). ‘Medieval Nine-Men’s Morris with Dice’. Board Games Studies vol. 3: pages 112–116. Research School CNWS: Leiden, Netherlands.

Bell, R. C. (). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (revised edition). Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-0-486-23855-5. First published in 1960 by Oxford University Press.

Stahlhacke, Peter (). ‘The Game of Lasker Morris’.

Goddard, A. R. (). ‘Find of another Nine Men’s Morris Stone: Comments of Mr. Goddard’. Saga-Book of the Viking Club vol. 3: pages 20–21.

Taylor, Arthur (). Played at the Pub. English Heritage: Swindon, England, UK. ISBN: 978-1-905624-97-3.