Tic-Tac-Toe

Last updated: .

Tic-Tac-Toe is a simple game for two players that is well-known to result in a draw if played ‘rationally’. Unlike most board games, pieces cannot be moved or removed once placed, making it an ideal game to play with pen & paper.

Some tic-tac-toe games.

History

The origins of tic-tac-toe are unclear. Many sources claim that it dates from antiquity, but the evidence to me suggests a more recent invention. Possibly it appeared as a degenerate version of Three Men’s Morris. Written references to the game only appear in the 19th century, and the game is particularly well-suited to being played with chalk on slates — standard equipment for schoolchildren during this period. Indeed, A Glossary of Berkshire Words and Phrases (164) describes it as “the first game taught to children when they can use a slate pencil”.

The small merels board with diagonals.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

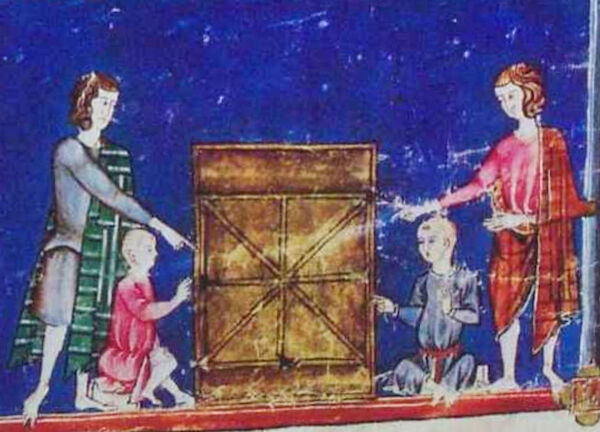

However, there is an early antecedent: a game equivalent in play, if not in presentation. Alfonso X of Castile’s Book of GamesB, published in 1283, includes the game alquerque de tres which is played on a small merels board with diagonals. Each player has three pawns which they place on the board one at a time, taking turns. If a player can form three-in-a-row then they win; otherwise it is a tie.

Later historians (even including H. J. R. MurrayC) have muddied the waters by describing this game as a three-men’s-morris game where the pieces can be moved after being placed, but this is not supported by the original manuscript.D (609) Thus, it is functionally equivalent to modern tic-tac-toe.

This image from Alfonso X’s Book of Games shows that alquerque de tres was considered a children’s game.

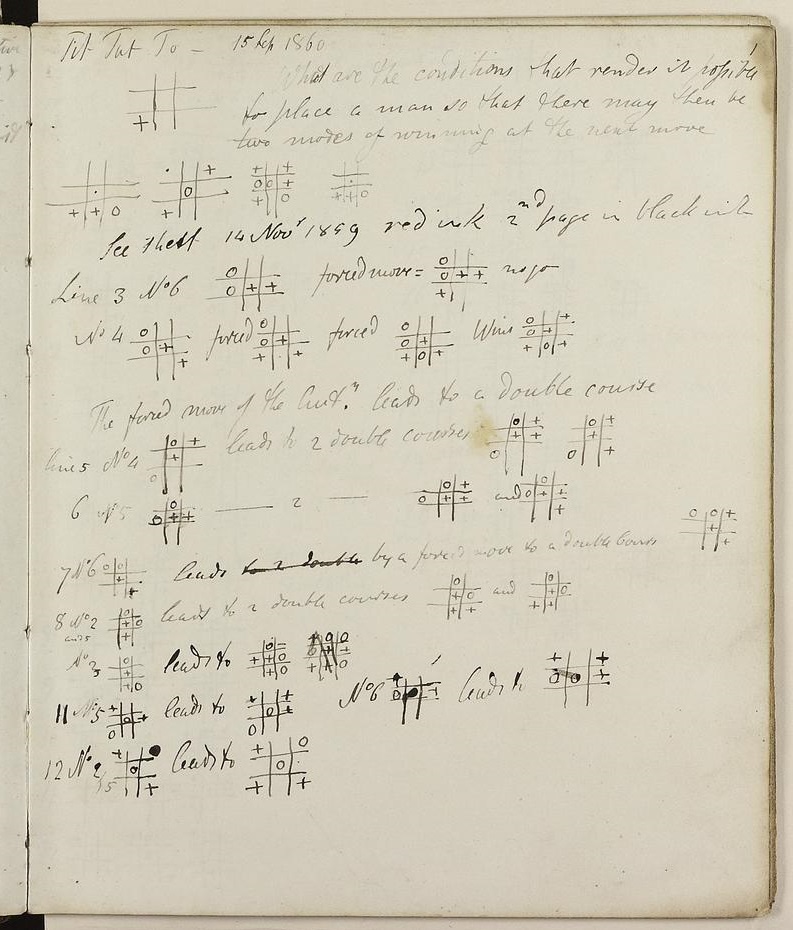

The earliest known written references to Tic-Tac-Toe in English occur in Charles Babbage’s unpublished manuscript Essays on the Philosophy of Analysis (1812–1820, now held in the British Library as Add. MS 37202), although the game is never mentioned by name.E Two decades later, in 1842, ‘tit-tat-to’ again occurs in his notebooks, when he conceptualizes an automaton that would play the game against a human — a very early vision of automated game-playing.EF

Another early reference appears in 1818 in an article on the Lancasterian system, during a discussion of children’s games:G

One boy who is acquainted with the popular game of checkers, fox andgeese, tit-tat-to, hop skip and jump, and a thousand other childish amusements, will communicate all he knows to his school companions with surprising facility.

In 1830, Robert Taylor (an anti-clerical Radical, nicknamed “the Devil’s chaplain”) used tic-tac-toe as an example of a children’s game in his sermon “The Star of Bethlehem”:H (7)

Just as a fool, who has but seen the diagrams and delineations in the elements of Euclid, will make himself dead sure that all the mathematics in the world could have consisted in nothing more than in making hobscotches [hop-scotch], and catgallowses [a high-jump], and scratchcradles [cat’s cradle], to play at tit-tat-toe with.

Some of Babbage’s notes on “Tit-Tat-To”, dated 15th–16th September 1860.

Terminology

In English, tic-tac-toe has gone by many names. It has been variously called ‘tit-tat-to(e)’, ‘tic(k)-tac(k)-to(e)’, ‘(n)oughts & crosses’, ‘crisscross’, ‘tip-tap-toe’,I (136)J (333) ‘Exeter’s Nose’ (a pun on ‘Xs and Os’),E ‘oxen-crosses’K (134), or ‘kit-cat-cannio’.L (200)

Several of these names derive from old counting-out rhymes — think ‘eeny meeny miny mo’ — that begin with ‘tit, tat, toe’. These rhymes date from at least the early 18th century: in 1725, A New Canting Dictionary described ‘Tit-Tat’ as “the aiming of Children to go at first”.

The rhyme seems to have fallen out of use before the 20th century; it is not recorded in books such as London Street Games (1916) nor The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (1959).

The fullest expression of this rhyme is along the lines of:

Tit, tat, toe,

My first go,

Three jolly butcher boys

All in a row;

Stick one up,

Stick one down,

Stick one in the old man’s crown!Some sources (e.g. Woodson (1871, 374)) give this last line as “… in the old man’s (burial-)ground!”; I have no idea what this means.

Aside from its use as a counting-out rhyme, ‘tit-tat-to’ was used to refer to any set of three lined-up objects — in F. W. N. Bayley’s 1842 adaptation of the gruesome Bluebeard fairy-tale, Mrs. Bluebeard discovers that her husband has murdered his six previous wives, and:P (19)

[…] —ah! no more!

She bumps her body down on the floor;

Down on the floor—and, Oh, my eye!

She looks as if she were ready to die!

It isn’t a case of “tit-tat-toe,”

And “three jolly butchers all of a row,”

But Oh . . . Oh . . . Oh . . ! ! !

It’s a double case of tit-tat-toe,

And Six Dead Women all of a Row.Supposedly this is a children’s book.

This usage of referring to neatly-aligned triplets is still current with the Swedish equivalent of tripp, trapp, trull (see more below). The three houses in Kalmar in the following image are nicknamed the “tripp trapp trull houses”:

The same rhyme and name were also used for an unrelated game, using a circular board, in which a player would attempt to locate high-scoring sections of a circle while blindfolded.R (55)

There seems to be a distinction we can draw between languages that have folkish names and those that have more functional names derived from the outward appearance or goal of the game.

In the ‘folkish’ group we have examples like the Dutch ‘tik tak tol’,U (122) or ‘boter-kaas-en-eieren’ (‘butter cheese and eggs’); and the Swedish ‘tripp, trapp, trull’.U (137)

Like the English names, one Dutch name (boter, melk, kaas) is derived from a rhyme:V (732)

Boter, melk, kaas,

ik ben de baas.Butter, milk, cheese,

I am the boss.

Sweden had a similar rhyme:W (163)

Tripp, trapp, trull,

min kvarn är full.Tripp, trapp, trull,

my mill is full.

In the ‘functional’ group of names are those like the Arabic لعبة إكس-أو ‘the X–O game’; or the Chinese 圈圈叉叉 ‘circles & crosses’, or 井字棋 ‘井 character game’.

The languages with ‘folkish’ names also tend to have ‘functional’ names as well; an alternate Swedish name is ‘tre-i-rad’ (‘three in a row’), and Dutch has the straightforward ‘kruisje rondje’ (‘cross circle’).

On the other hand, the English poet Wordsworth didn’t think the game was worthy of a name at all. In The Prelude, he describes playing the game as a child:X (ll. 538–544)

Eager and never weary we pursued

Our home-amusements by the warm peat-fire

At evening, when with pencil and smooth slate,

In square divisions parcelled out, and all

With crosses and with cyphers“cyphers” here means “zeroes” scribbled o’er

We schemed and puzzled, head opposed to head

In strife too humble to be named in verse

A tic-tac-toe game on a wall in Marseille, France.

© Nicolas Nova, 🅭🅯🄏

Other languages

In Greek it is called τρίλιζα (triliza), or πατητό (patito) in Thessaloniki.This is given in [Y] as “butito”, played in Larnaca on Cyprus. Patito (‘stepping’) is also used for hopscotch.

Play

Two players take turns marking spaces in a 3×3 grid, one using the symbol ‘X’ and the writing ‘O’. Traditionally the starting player uses the ‘X’. The first player to place three of their marks in a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal row wins. If all nine spaces are filled without either player achieving three-in-a-row, the game ends in a draw (drawn games are referred to as “cat’s games”, supposing that the cat won them).

With perfect play from both sides, the game always ends in a draw — a fact shown by Babbage’s original analysis in the 19th century, but which is also obvious from playing the game a few times.

Strategy

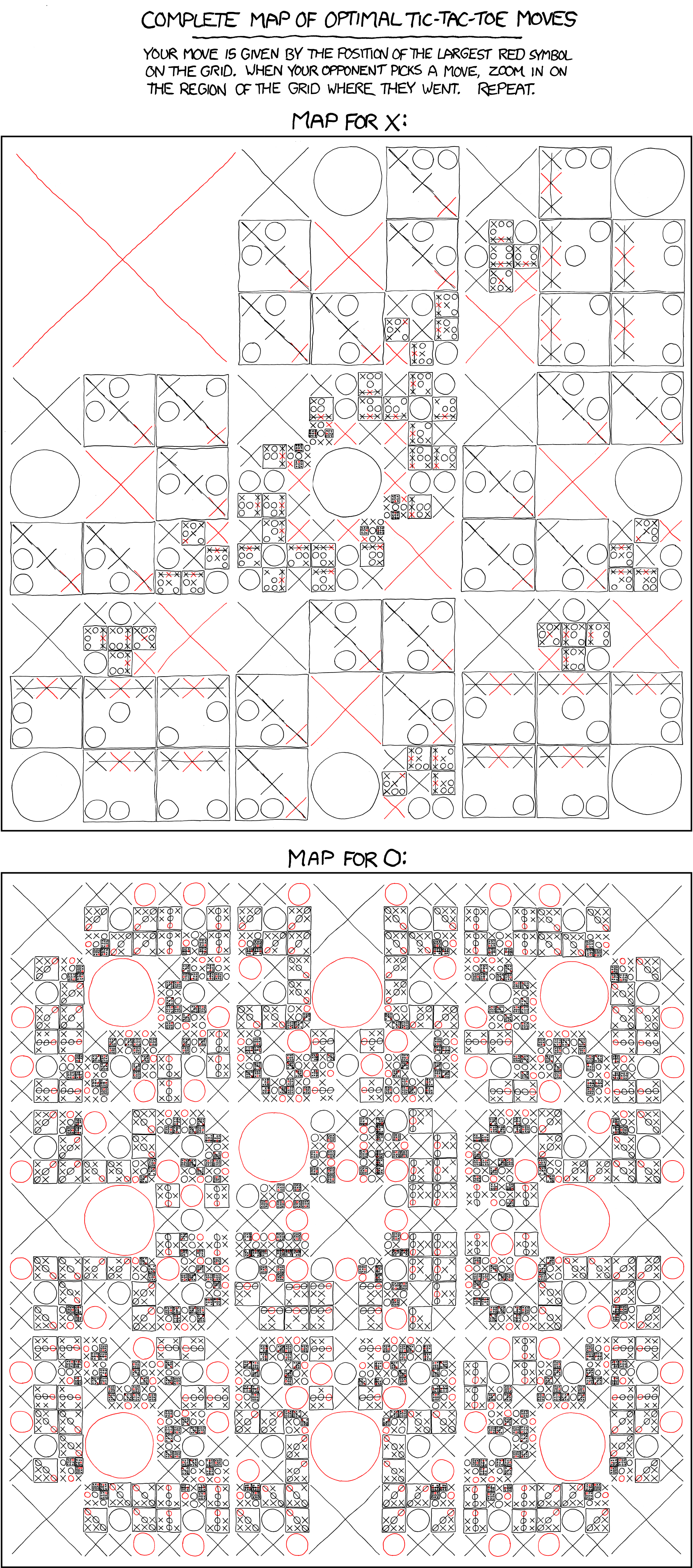

The strategy of tic-tac-toe is straightforward enough to be completely solved. The first player can force a win only if the second player makes a mistake; otherwise, optimal play will always result in a draw.As Randall Munroe (xkcd #832) states: “The only winning move is to play, perfectly, waiting for your oppenent to make a mistake.”

A nice analysis of winning strategies can be found in Hexaflexagons and other mathematical diversions, as Gardner focuses on optimizing the opportunity to win (pages 45–6).

Randall Munroe also produced this ‘map’ of optimal moves, which can be followed to ensure a draw:

A map of optimal moves in tic-tac-toe, from xkcd comic #832.

© 2010 Randall Munroe, 🅭🅯🄏

Variants

The following variants are mathematically isomorphic to tic-tac-toe — that is, they have identical structure (and thus, strategy) despite appearing completely different.

The 15 Game

This game is also known as “Number Scrabble”AA or “Pick15”.

To play: Write down the numbers from 1–9 on a piece of paper. Each turn, a player claims a number for themselves by marking it, and a number can only be claimed by one player. The first player to claim 3 numbers that add to 15 is the winner.

Astonishingly, this isomorphic form was invented by Babbage in his initial analysis of the game.AB (127)

To show the equivalence, write down the numbers in the form of the (unique) 3×3 magic square:

4 | 9 | 2 |

3 | 5 | 7 |

8 | 1 | 6 |

From this it can be seen that the game is the same as tic-tac-toe. Each row, column, and long diagonal sums to 15.

JAM

This variant was invented by John Michon.AA It is the projective geometry dual of the standard game, where each cell is replaced by a line and each winning line by a point, in such a way that each cell-line intersects the appropriate winning-line points.

If this is confusing, muse upon the following diagram: the red solid vertical line represents the middle cell of the Tic-Tac-Toe board; it crosses four points (winning lines). The four blue dashed lines are the corner cells, which cross three points (winning lines) each, and the four green dotted lines are the side-centre cells, which cross two points (winning lines) each.

The JAM board.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

To play, players take turns claiming an entire line, which crosses several points. Once a player has claimed a line it may not be claimed by the other player. The first player that claims all three lines that pass through any single point wins the game.

Spit

Yet another variant is played as follows:V (732)

Write down the nine words ‘Spit’, ‘Not’, ‘So’, ‘Fat’, ‘Fop’, ‘As’, ‘If’, ‘In’, and ‘Pan’ on separate pieces of paper. The players take turns taking a single card. A player wins if they collect all the cards with a given letter (e.g. ‘In’, ‘If’, and ‘Spit’ would win since these are all the words containing ‘i’).

This can be shown to be the same game in the following way (note that the number of letters in each word is the same as the number of lines that can be formed through that square):

P | N | S | F | T |

A | PAN | AS | FAT | A |

I | IN | SPIT | IF | I |

O | NOT | SO | FOP | O |

T | N | S | F | P |

Tic-tac-toe games on a wall in the Medina of Fez (فاس البالي), Morocco.

© henrykkcheung , 🅭🅯🄏⊜

Automatic Players

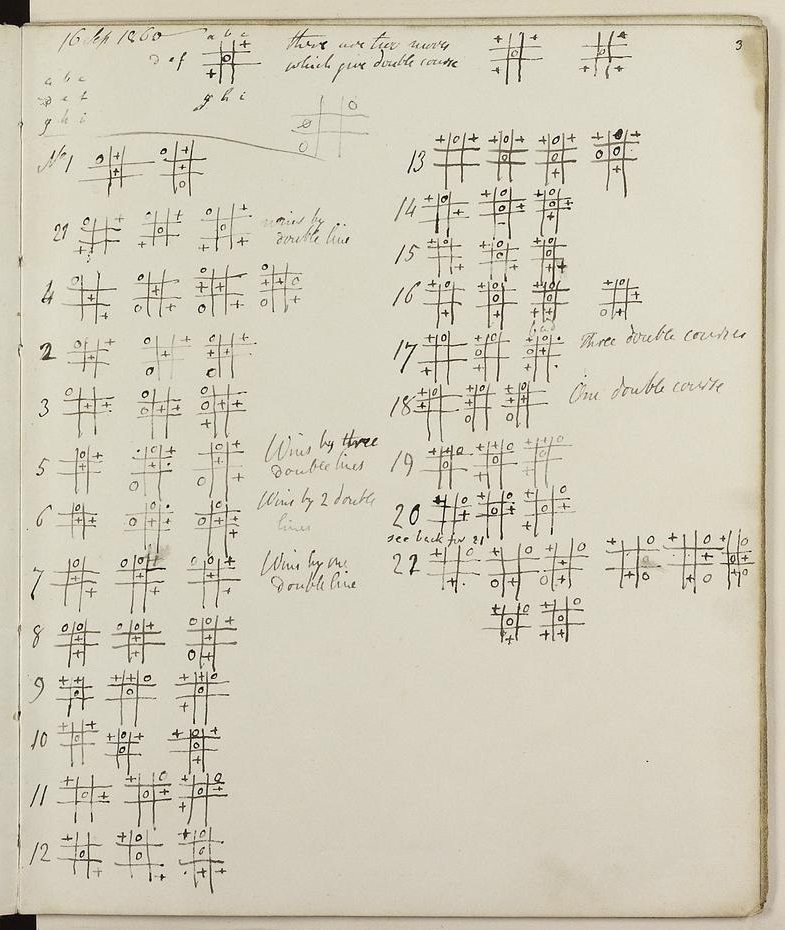

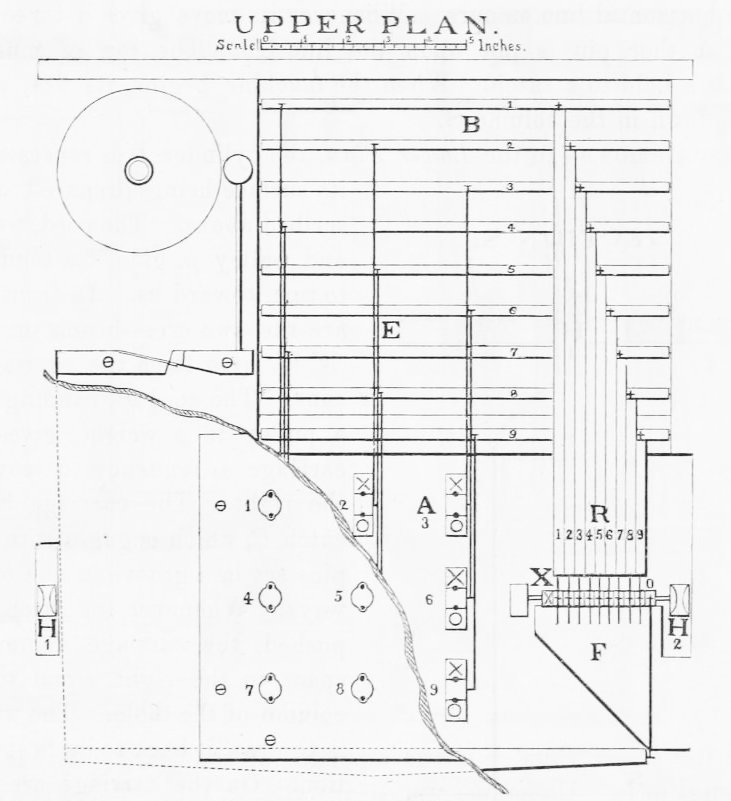

Being a simple game with a finite game tree, Tic-Tac-Toe is both easily programmed and ideal for early automation experiments, and so became one of the first games to be played by machines. As noted above, Charles Babbage studied the problem but never built an actual machine.

The earliest fully automated player was constructed by a Frank T. Freeland of Philadelphia, who described its implementation in an 1879 journal article.AC According to the article, the machine was built and exhibited in 1878 before being moved to the University of Pennsylvania. Its whereabouts (if it still exists) are currently unknown.For more about Freeland, see [AD]. This machine predates any other implementations by some 70 years!

Freeland’s input device and cylinder layout (for selecting an appropriate response).

Later (but still early, in the computing world) implementations of the game include:

Bertie the Brain (analog, 1950)

OXO (for the EDSAC, 1952)

Relay MoeAE (relay-based, 1956), the first to be programmed with a variable strategy and with a chance of making a mistake

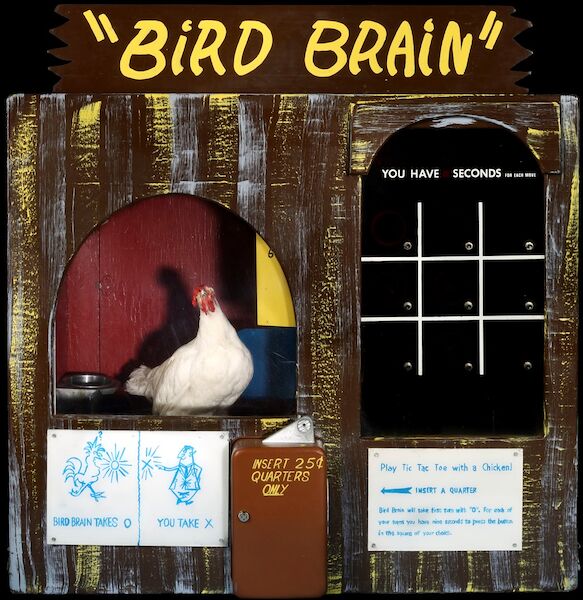

Chickens have also been trained to ‘play’ the game.AFAGAH The first of these games, “Bird Brain”, was developed in the late 1970s by Animal Behavior Enterprises, a company founded by Marian & Keller Breland, who were students of B. F. Skinner, the behavioural psychologist.AI (73) In reality, the game is rigged—the chicken only ever pushes a single button, and the move to be played is chosen by a computer.AJ

A surviving copy of Animal Behaviour Enterprises’ Bird Brain game.

© 2004 Smithsonian, under US fair use

See also

Some general references for the game are The Oxford History of Board Games (112–3), Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (vol. 1, p. 91), and A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess (§3.2.1, p. 40).

Gardner has further discussion on variants in Wheels, Life, and Other Mathematical Amusements (94–105).

References

Lowsley, Barzillai (). A Glossary of Berkshire Words and Phrases. English Dialect Society: London, UK.

Alfonso X (). Libro de açedrex, dados e tablas. Alfonso X: Toledo, Spain.

Murray, H. J. R. (). A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, UK. ISBN: 0-19-827401-7.

Golladay, Sonja Musser (). Los Libros de Acedrex Dados e Tablas: Historical, Artistic, and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X’s Book of Games. PhD thesis, University of Arizona: Arizona, USA.

Singmaster, David (). ‘Sources in recreational mathematics’ [archived].

Monnens, Devin (). ‘“I commenced an examination of a game called ‘Tit-Tat-To’”: Charles Babbage and the “First” Computer Game’. In Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA international conference: DeFragging Game Studies volume 7.

Pickett, John (). ‘The New School; or Lancasterian System’. The Academician (1), : page 91. John C. Francis: London, England, UK.

Taylor, Robert (). The Devil’s Pulpit: or Astro-Theological Sermons. Calvin Blanchard: New York.

Frederick, Dinsdale (). A glossary of provincial words used in Teesdale, in the county of Durham. J. R. Smith: London, England, UK.

John C. Francis (). Notes and Queries volume 12 (Series 8). John C. Francis: London, England, UK.

Norman, Douglas (). London Street Games. St. Catherine Press: London.

Moor, Edward (). Suffolk Words. J. Loder: London, UK.

Anonymous (). A New Canting Dictionary. London, UK.

Opie, Iona and Peter Opie (). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford University Press: United Kingdom.

Woodson, W. W. (). ‘The Nursery Witch’. Our Monthly vol. 3: pages 371–375. The Presbytarian Magazine Company: Cincinnati.

Bayley, F. W. N. (). Comic Nursery Tales (3rd edition). WM. S. Orr & Co.: London.

Monkhouse, Cosmo (). ‘Some pictures of Children’. The Magazine of Art vol. 7: pages 133–137. Cassel and Company: London, Paris, and New York.

Ernest Nister (). The Games Book for Boys and Girls. Ernest Nister: London, UK.

Skeat, Walter W. (). ‘“Tit-Tat-To”’. Notes and Queries vol. 9 (28), : page 26.

Doornkaat Koolman, Jan ten (). Wörterbuch der Ostfriesischen Sprache [text in German] volume 3: ‘Q–Z’. Herm. Braams: Norden, Germany.

Fiske, Willard (). Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic literature, with historical notes on other table-games. The Florentine Typographical Society: Florence.

Berlekamp, Elwyn, John Conway, and Richard Guy (). Winning Ways volume 3 (2nd edition). A K Peters: Natick, MA, USA. ISBN: 978-1-56881-143-7.

Pennick, Nigel (). Games of the Gods: The origin of board games in magic and divination. Samuel Weiser: York Beach, ME, USA. ISBN: 0-87728-696-5.

Wordsworth, William (). The Prelude. Edward Moxon: London, UK.

Anonymous (). ‘Butito’. The Australian Children’s Folklore Newsletter (11), : pages 12–13.

Gardner, Martin (). Hexaflexagons and other mathematical diversions. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA. ISBN: 0-226-28254-6. First published in 1959.

Michon, John (). ‘The Game of JAM: An Isomorph of Tic-Tac-Toe’. The American Journal of Psychology vol. 80 (1), : pages 137–140. University of Illinois Press: IL, USA.

Dubbey, John (). The Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511622397.

Freeland, Frank T. (). ‘An Automatic Tit-Tat-To Machine’. Journal of the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania vol. 102 (1): pages 1–9.

Fine, Thomas A. (). ‘The Mystery of the Victorian Tic-Tac-Toe Computer’ [archived]. On the website Sentence Spacing (accessed ).

Berkeley, Edmund C. (). ‘“Relay Moe” Plays Tick-Tack-Toe’. Radio-Electronics, : pages 50–52.

Kaufman, Michael (). ‘Cross Out a Landmark On the Chinatown Tour’. The New York Times, .

Trillin, Calvin (). ‘The Chicken Vanishes’. The New Yorker, : pages 38–41.

Gregory, Kia (). ‘Chinatown Fair Is Back, Without Chickens Playing Tick-Tack-Toe’. The New York Times, .

Marr, John N. (). ‘Marian Breland Bailey: The Mouse Who Reinforced’. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly vol. 61 (1): pages 59–79.

Animal Behavior Enterprises (). ‘Bird Brain Manual’ [archived]. Animal Behavior Enterprises.

Parlett, David (). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, UK. ISBN: 978-0-19-212998-7.

Bell, R. C. (). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (revised edition). Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-0-486-23855-5. First published in 1960 by Oxford University Press.

Gardner, Martin (). Wheels, Life, and Other Mathematical Amusements. W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA. ISBN: 0-7167-1588-0.