ꦥꦺꦲꦶ · Pèi

Last updated: .

Pèi (ꦥꦺꦲꦶ) was a fishing game for three players from Java, which used Ceki cards. The goal of the game is to capture specific scoring combinations.

The game was also called ꦥꦺꦲꦶ pèhi or ꦥꦺꦃꦱꦶ pèhsi;A thus the name might be derived from the Hokkien 白魚 pe̍h-hî.

The description below is based upon Javaanse Kaartspelen [Javanese Card Games] (p. 58–70).

According to the article, at that time the game was usually played on the ground or on a mat, but women played it at a table. Amongst older people it was considered a refined game, and luck or misfortune in the game was considered to correspond to luck or misfortune in the rest of a player’s life.

The game as played in Surakarta and Yogyakarta was the same, but different terminology was used, and some bets differed.

Play

The game is played by three players with two sets of ceki

cards (120 cards total). If there are four players, then three will take part in the game while the fourth player acts as the dealer and point-counter (makao in Surakarta or matang atusi in Yogyakarta).

To decide seating order, each player is dealt two cards; the sum of their values determines (from highest to lowest) who will be ꦫꦗ raja ‘king’, ꦥꦠꦶꦃ patih ‘councillor’, and ꦲꦸꦚꦶꦏ꧀ unyik ‘last’.

The dealer (or last player, if there are only three) deals 7 cards face-down and 6 cards face-up to each player, then repeats this so that each player has 14 cards to form their hand and there are 36 cards face-up on the table, which form the central pool. The remaining 42 cards are placed face-down to form the stock.

The dealer then arranges the cards in the centre of the table by rank to make them easier to find; usually they are formed into a square around the stock pile, with nines and ones in front of the raja, eights and twos in front of the patih, sevens, threes, and fives in front of the unyik, and sixes and fours on the side of the dealer.

The top card of the stock is then turned face-up next to it. This will be the last card drawn and thus will go to the unyik. The unyik can then use this to plan their last move of the round.

The patih is then permitted to look at the top card of the deck, which will be the second-to-last card drawn and thus their last card of the round, but it is not shown to the other players, and is replaced upon the top of the deck.

On each player’s turn, first they play a card from their hand, trying to match one of the face-up cards by rank. If they can, they capture both cards. If they cannot make a match, their played card is left face-up with the other cards on the table. After this, they draw a card from the stock and again try to match a card by rank. Captured cards may be kept either face-up or face-down, depending on the players.

Unusually, cards are drawn from the stock by passing it around and drawing cards from the bottom.This feature is also recorded by Ki-Tong Tcheng, see below. The stock pile may be split into multiple sections to make this easier, making sure to leave the pile with the patih’s card for last. The unyik’s card remains face-up in the middle, alongside any money placed there for bets.

The round continues until players have used up all the cards in their hands. If some cards are unmatched at the end of the game then they are left on the table.

The dealer (if any) arranges the player’s cards by scoring combinations and counts the points (apparently grouping them into sets of 25 makes this faster). Any cards that are not part of a combination score their face value (rank).

The player with the highest score is ngeté (‘payment getter’?),The book suggests te is from Chinese 貯 ‘hoard, savings’. the second is tengah ‘centre’ or jangga ‘neck’?, and the last is kete (‘payment giver’?).

Scoring Combinations

There are five possible scoring combinations. (When there are multiple Javanese names given, the first is in the everyday ngoko register and the second is in the polite krama register; see the Javanese Wikipedia article for more.)

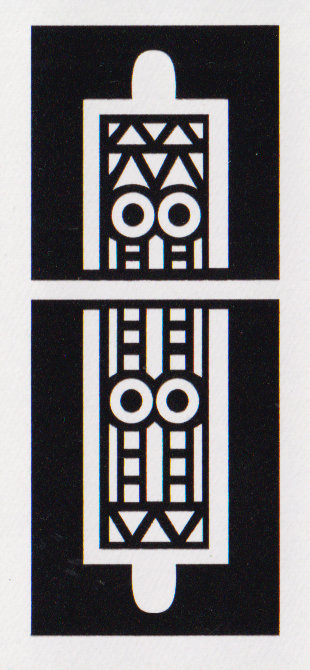

Black Thirteen (ꦧꦸꦚ꧀ꦕꦶꦲꦶꦉꦁ bunci ireng · ꦧꦸꦚ꧀ꦕꦶꦕꦶꦩꦷ bunci cimii)

This combination consists of the first three cards of the coin suit, in order. The combination may be extended by capturing more of the coin cards in unbroken sequence. This gives 13 points per card in the sequence, so three cards scores 39, four cards scores 42, etc.

The maximum score possible would be all 9 cards for 113 points.

The first three cards of the coin suit must be obtained in order to score bunci ireng.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

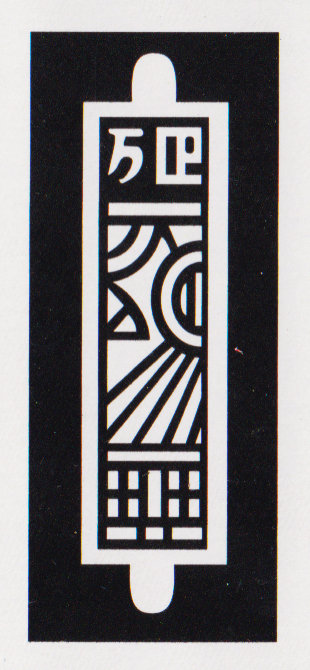

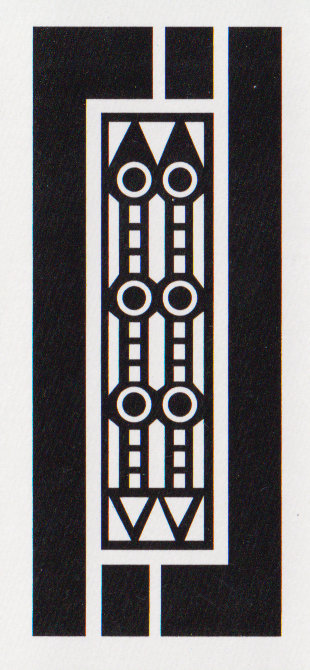

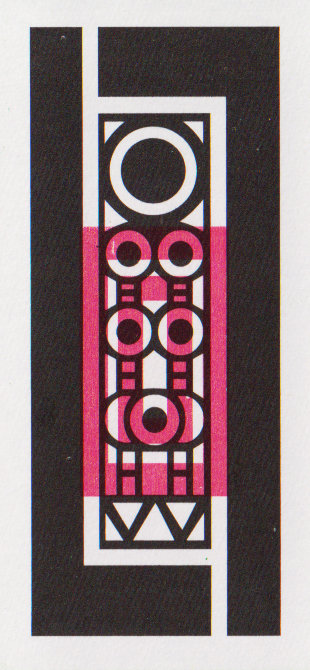

Red Thirteen (ꦧꦸꦚ꧀ꦕꦶꦲꦧꦁ bunci abang · ꦧꦸꦚ꧀ꦕꦶꦲꦧꦿꦶꦠ꧀ bunci abrit)

This combination is formed from one of each of the three red-stamped cards. It is worth 13 points per card, so at least 39 points. Any additional cards of the same type add 13 points each.

The red-stamped cards.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

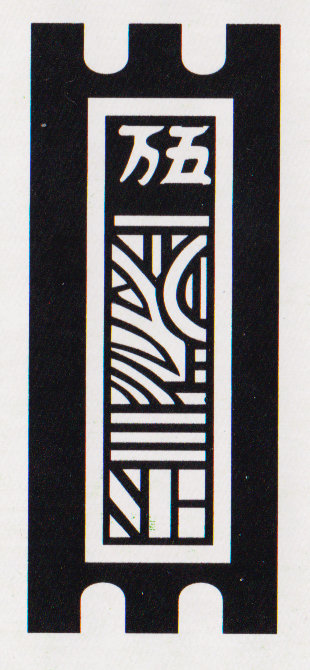

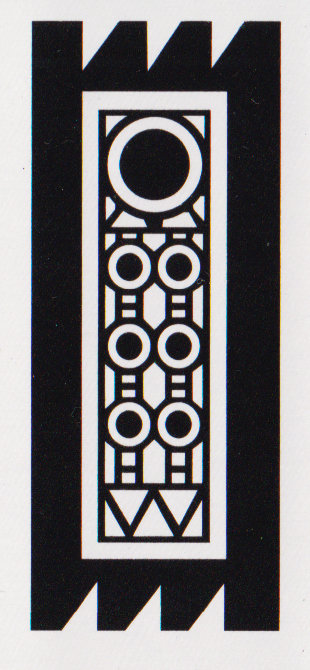

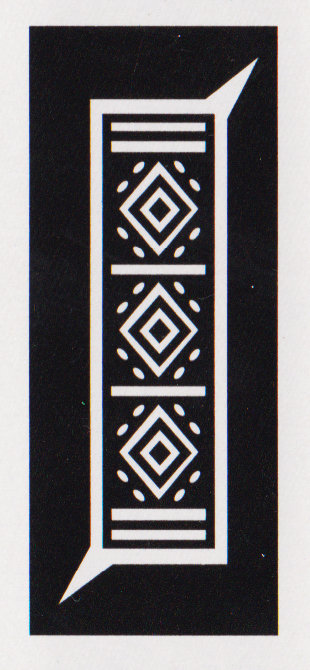

Pang Kéyang (ꦥꦁꦏꦺꦪꦁ pang kéyang)

Sometimes simply ꦏꦺꦪꦁ kéyang.

This combination is formed from one of each of White Flower, 8 of strings, and 9 of myriads. It scores 12 points per card (base 36 points), and 12 for each additional card.

The cards for Pang Kéyang.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

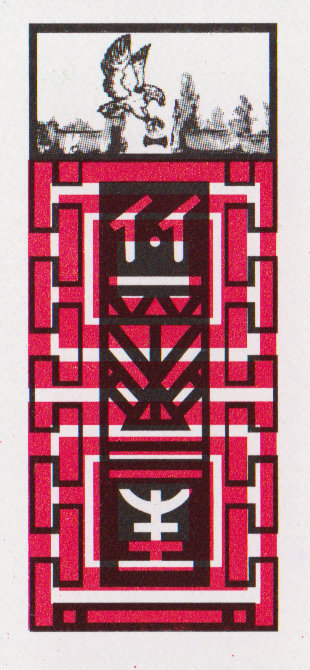

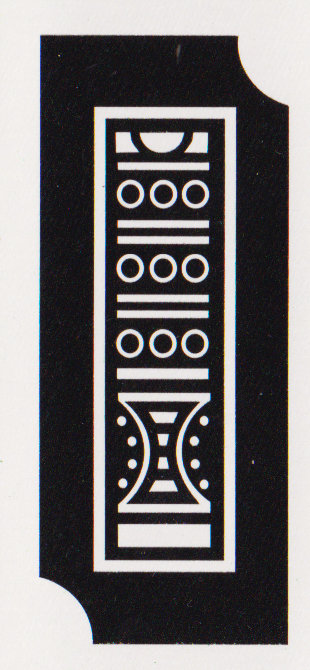

Coin Pang (ꦥꦁꦥꦶꦕꦶꦱ꧀ pang picis)

Sometimes simply ꦥꦁ pang.

This combination is formed from one of each of the 8 of coins, 2 of strings, and 2 of myriads. It scores 11 points per card (33 points), and 11 for each additional card.

The cards for Pang Picis.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

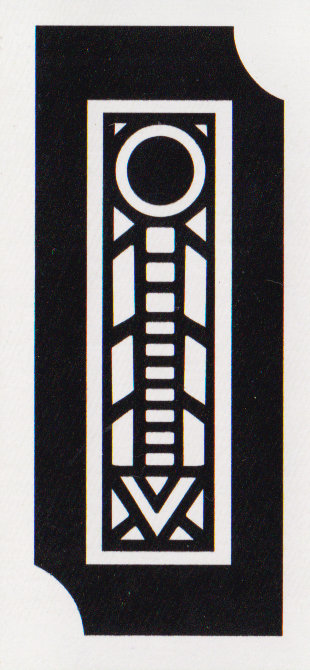

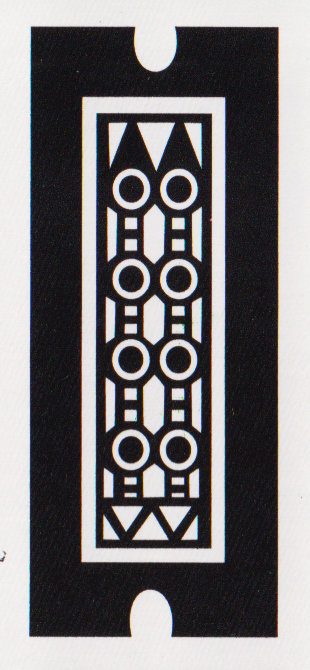

Tiger (ꦩꦕꦤ꧀ macan · ꦱꦶꦩ sima)

This combination is formed from one of each of the 1 of coins, 9 of strings, and 1 of myriads. It scores 10 points per card (30 points), and 10 for each additional card.

The cards for Macan.

© George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎

Possible bets

Firstly, the game can be played without a stake (jentolan ‘stings’?); in this case, whoever loses becomes the dealer and must shuffle, deal, and count for the next round.

Ways to bet with money include:

Totohan wudon ‘middle stakes’: each player bets a fixed stake into the pot, the winner taking ⅔ and the second taking ⅓. If the winner manages to obtain at least 350 points then they take the whole pot.

Totohan bayaran/rampung ‘payment stakes’ or ‘settled stakes’: players pay bets to each other based upon the following scheme:

té lumrah (‘normal payment’): if the player achieves at least 200 points (example value 5¢), paid by the loser to the winner (but not by the middle player)

té mati (‘dead payment’): if the player fails to achieve 200 points (example value 10¢), paid to the winner

belahan (‘split’): if the winner achieves 350 points (example value 10¢), paid by both other players

patang atusan (‘four hundred’): if the winner achieves 400 points (example value 10¢), paid by both other players

Note that the bets are cumulative; if the winner achieves 400 points they will receive both belahan and patang atusan.

In addition, players can pay to each other the jung based upon the difference in scores, for example 5¢ for every 10 points (rounded up). If the winner has 354, the middle 322, and the loser 275, then the winner takes (32pts = 4×5¢) 20¢ from the middle and (79pts = 8×5¢) 40¢ from the loser, and the middle takes (47pts = 5×5¢) 25¢ from the loser.

Toh paréwanan (‘reckless stakes’): this is the combination of wudon and rampung at the same time.

Wul-wulan (Surakarta, something about the moon?) or nir (Yogyakarta, ‘on edge’): stakes are paid into the pot and are taken by the first player to reach 400 points. If no one does, then additional stakes are added into the pot each round until someone achieves 400 points. Thus, this betting method functions like a jackpot. Toh jedhil (Yogyakarta, ‘extract stakes’) is similar to this but if no one wins 400 points, bets are not added, and small amounts are taken from the pot (e.g. if the wagers are 25¢ then the winner gets 10¢ and second 5¢; if the winner gets 350 points 15¢, and if 400 points 20¢). When the pot runs too low it is replenished.

Variants

The Chinese game

The Chinese version of this game is described under the (French) name of la pêche (‘fishing’) by Tcheng Ki-tong.C (p. 270)See also the English translation of this work, Bits of China (p. 205). Presumably the Chinese name is 釣魚 (Hokkien: tiò-hû), which is also shared by a domino game which uses the fishing mechanic.E (p. 511)

The game is for three players, and uses two decks (120 cards). To deal, the deck is divided into 8 packs of 14 cards, with 8 cards left over. Dice are used to select three packs which will be used as a stock (of 42 cards). Another two packs are selected and combined with the 8 extra cards — these cards will form the central pool of 36 cards. Lastly the three remaining packs are allocated to the players. The last player spreads the pool cards out face up, and also is allowed to look at the last card in the stock to compensate for playing last. Since they are the last player they will receive this card at the very end of the round, so they can know what to expect.

Each player then takes turns as usual, playing a card from the hand and one from the (bottom of) the stock. Captures are made by matching rank only.

The combinations used are identical and score the same, but there are no bonuses for obtaining extra cards above the ones included in the combination. Any extra cards score their face value.

Pei Magelang

In the version as played in Magelang,B (p. 67–8) the scoring combinations are counted differently:

macan scores 10 points per card (as usual)

pang picis and pang kéyang score 20 points per card

bunci ireng and bunci abang score 30 points per card

Derivation of the Combinations

In Javaanse Kaartspelen [Javanese Card Games] (p. 58) it is suggested that the name of the game comes from the Chinese game Fishing for Hairtails, but that is played with (two-colour) chess playing cards, and doesn’t have any sequence collection.

In fact, the game is closely related to the Chinese game of Kànhǔ, and so I believe the name probably comes from the Chinese word for playing cards, 牌 (Hokkien: pâi).

The combinations in particular are copied directly from the Kànhǔ scoring combinations called ‘eyes’ (眼). The odd combinations of cards are explained by the historical ordering of the deck (see its article for more on this), in short, the suit of coins used to rank in reverse. White Flower derives from the half-coin card and Red Flower from the zero-coin card, so they rank above all other coins.

Given this information, we can arrange the deck as follows, and we can easily see how the combinations were arrived at:

low | high | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Myriads |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 | |

Strings |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 | ||

Coins |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |  © George Pollard, 🅭🅯🄏🄎 |

The scoring combinations of Pei are then explained in this way, with their matching Kànhǔ combinations (I do not have names for all of them):

駕 ‘carriage’, equivalent to bunci abang, the highest (red-stamped) cards in each suit

pang kéyang is made up of the second highest cards in each suit

窮 ‘poverty’, equivalent to pang picis, the second-lowest cards in each suit

虎 ‘tiger’, equivalent to macan, the lowest cards in each suit

bunci ireng is made up of the highest cards in the coins suit (1, 2, 3), which is also an ‘eye’

References

de Clercq, Frederik Sigismund Alexander (). ‘Verklaring van het Péhi-spel’ [text in Dutch] [archived]. Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde vol. 23: pages 512–516.

Siem, Tjan Tjoe [曾祖沁] (). Javaanse Kaartspelen: bijdrage tot de beschrijving van land en volk [Javanese Card Games; text in Dutch]; Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen volume 75. A. C. Nix & Co.: Bandung, West Java, Indonesia.

Tcheng, Ki-tong [陳季同] (). Les Plaisirs en Chine [text in French]. G. Charpentier et Cie.: Paris.

Tcheng, Ki-tong [陳季同] (). Bits of China, translated by R. H. Sherard. Trischler and Company: London.

Culin, Stewart (). Chinese Games with Dice and Dominoes. Government Printing Office: Washington.